That the SA economy has performed quite as poorly as it has in recent years is not easily explained. The rate of growth of less than 2% a year represents a very poor outcome, with alas little prospect of any lift off, according to the economic forecasters in and outside government. Yet there are more corrupt economies with much less of an endowment of capital and skills that grow faster.

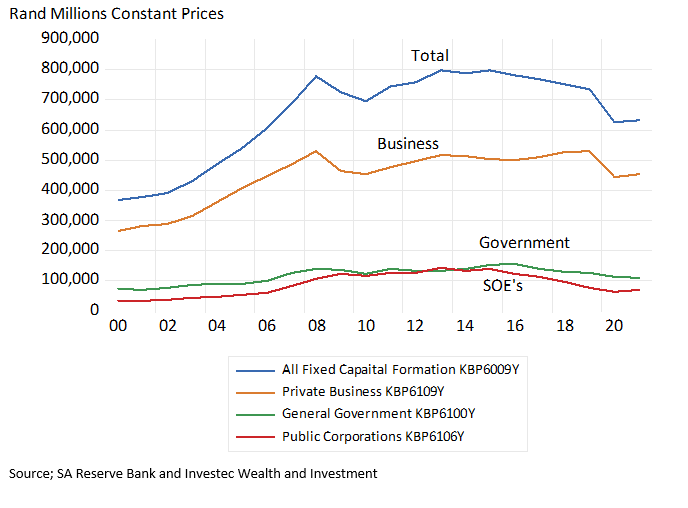

Fixed capital formation and employment offered by private businesses is at best in a holding pattern – capital formation being maintained at levels first reached in 2008. Capital formation by the public sector is in sharp decline- necessarily so – given past performance. The unwillingness of SA business to invest in future output and income generation and in their workforces – describes slow growth – but does not explain its causes. Such reluctance needs to be understood and addressed if the outlook for the economy is to improve.

Fixed Capital Formation Constant 2015 Prices

Source; SA Reserve Bank and Investec Wealth and Investment

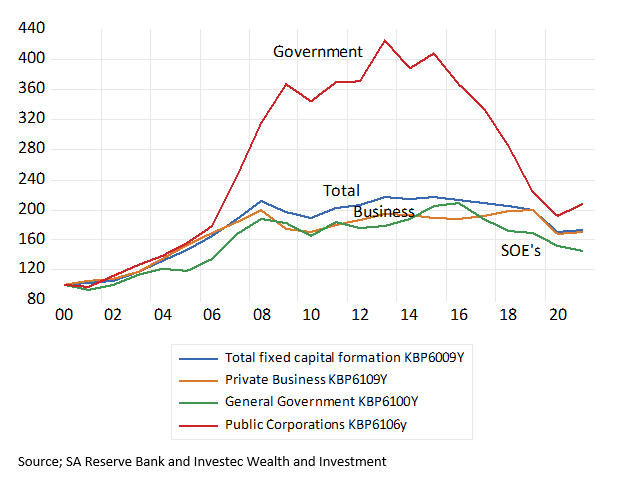

Total Real Fixed Capital Formation (2000=100)

Source; SA Reserve Bank and Investec Wealth and Investment

We need look no further for a large part of the explanation of unusually slow growth than to the disastrous failures of the SA public sector. South Africa relies heavily on the State as a producer of essential services, including electricity, water, transport, ports and education. More heavily than is wise or necessary. The inability of Eskom to meet depressed demands for electricity clearly sets limits to growth as do the failures of Transnet to run the railways and ports anything like competently.

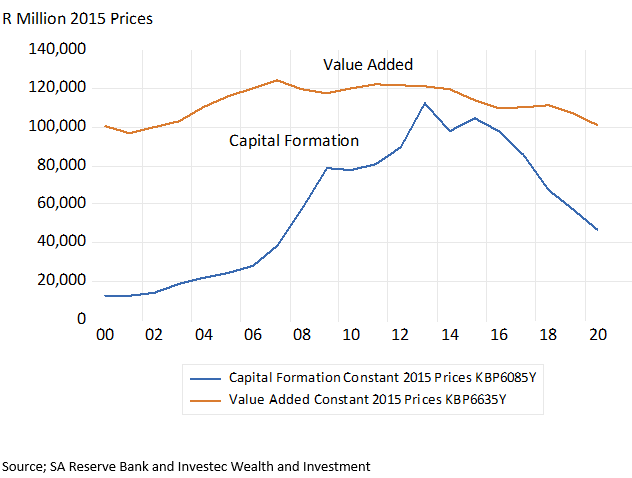

These operational failures have meant very large amounts of wasted, taxpayer and consumer provided capital and opportunity. The relationship between what has been spent on the large new electricity generating stations Medupi and Kusile and what has come out as additional electricity is especially egregious and damaging. As much as 1.1 trillion rands was invested in electricity, water and gas between 2000 and 2021. Much of it in electricity generation. Shockingly, almost unbelievably, the real output of electricity etc. has declined by 20% since 2000.

Electricity, gas and water. Capital Formation; Constant (2015) and Current Prices

Source; SA Reserve Bank and Investec Wealth and Investment

Electricity, gas and water. Capital Formation and Valued Added 2000- 2020. Constant 2015 Prices

Source; SA Reserve Bank and Investec Wealth and Investment

The abject failures of other government agencies – of the provinces and in particular municipalities – to maintain the quality of the essential services they are tasked to provide, water, roads, sewage, building plans, education training and health care etc. has become ever more destructive of the opportunities open to business and households. Such failures are also reflected in the declining real value of the homes South Africans own –a large percentage of the wealth of the average household – which has made them less able and willing to demand additional goods and services from SA business.

Hopefully the economy will not stay on these destructive paths. Restructuring the ownership and incentive structures facing the public sector is an obvious and urgent requirement for faster growth- for more capital formation of the human and physical kind. As is reducing the reliance on the public sector to deliver the essentials.

But we need a meta explanation and understanding of why the public sector has failed South Africans so particularly badly to move forward. The key political objective on which the public sector leaders were evaluated was clearly not the efficient use of resources, with quality of delivery related rewards, within sensibly constrained budgets. The Scandinavian model, if you like, did not apply. The primary objective set the new leaders of the public sector – and for which they were presumably judged and rewarded – was the transformation of the racial character of the public sector workforce.

It is an economic truism that you get from people (managers and workers) what you pay them for. This key performance indicator, transformation, has been achieved with huge waste, financial and in foregone opportunities. Losses that were exaggerated by the opportunities the lack of attention to the costs of operations, and their value to consumers, offered for theft, fraud and the patronage of the incompetent.

The continued enthusiasm for demanding that the private sector to transform further and faster seems uninhibited by any comparison of the cost and benefits of forcing transformation. There is perhaps one consolation in all this- the private sector cannot ignore the bottom line in the way the public sector was able to do for so long.