Property rights underpin wealth creation and are essential for attracting investment and helping communities to escape deprivation.

I once asked a meeting of law students if they knew why we have laws to protect our wealth and enforce the sanctity of contracts. They appeared to have little idea why, other than that it was morally wrong to steal, to perpetuate a fraud or not to be true to your word. Nobody had told them that protecting the rights to wealth was essential if wealth was to be created in the first instance.

If you saved and invested in a home, farm, mine or business enterprise, and somebody, stronger than you, could simply take it away, there would be no reason to save and invest in productive, long-lasting assets. Protection of wealth to encourage wealth creation is essential if any community is to become more productive and escape deprivation.

The power of a government to take what might be yours, gained fairly in exchange, is one of the obvious dangers to be averted in the public interest of increasing saving and capital expenditure. While there might be good cause for a compulsory purchase to advance a broad public interest, it should be facilitated by offering the market value of the asset as compensation. No compulsory expropriation without compensation is enshrined in our Constitution and legal practice, for good, income-enhancing reasons.

Having to offer full compensation to any owner is something of a deterrent to exercising any compulsory purchase order. The taxpayer, who also has political influence, will have to pay up for the assets. It’s an influence that is resented by those who have ambitions to change the world for what they believe will be the better and are frustrated by the lack of the means to do so. Just pay for what you wish to take, is the principle we should defend and honour.

South Africans are not just reluctant taxpayers. We are reluctant savers and maintain an unsatisfactory rate of capital accumulation. We still have to rely on foreign savings on a significant scale. We are dependent on capital that can be freely invested anywhere and is easily frightened off by threats to its being taken away by expropriation, or by changes in regulations affecting its market value.

The mere hint of expropriation of land and real estate, without compensation, makes foreign capital more expensive. Foreign investors command high expected returns to compensate for the risk of our taking it away or interfering with it. Hence our low rate of capital formation. An on-average risky JSE-listed company, to justify any addition to its plant and equipment, would have to offer a return of over 15% a year, or about at least a real 9% after expected inflation of about 6%. These are returns that few companies can confidently budget for.

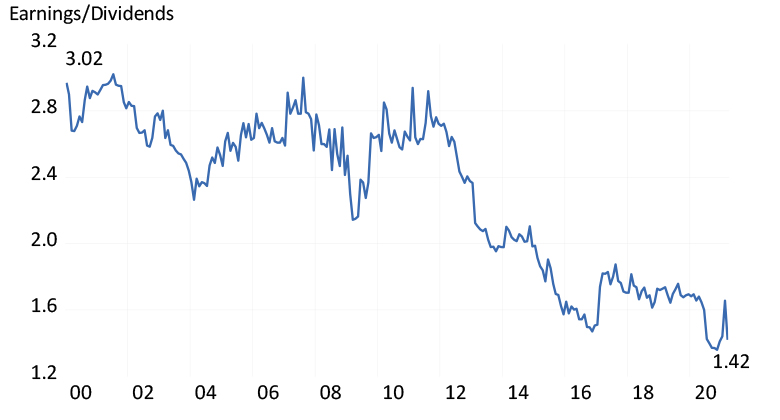

Hence businesses are investing less, and saving less, by paying out more of their earnings in dividends. The ratio of JSE earnings to dividends has halved since 2010. They are retaining less because they are investing less in capex, for understandable reasons.

Figure 1: Ratio of JSE All Share Index earnings per share to dividends per share

Ratio of JSE All Share Index earnings per share to dividends per share chart

Source: Iress and Investec Wealth & Investment, 12/04/2021

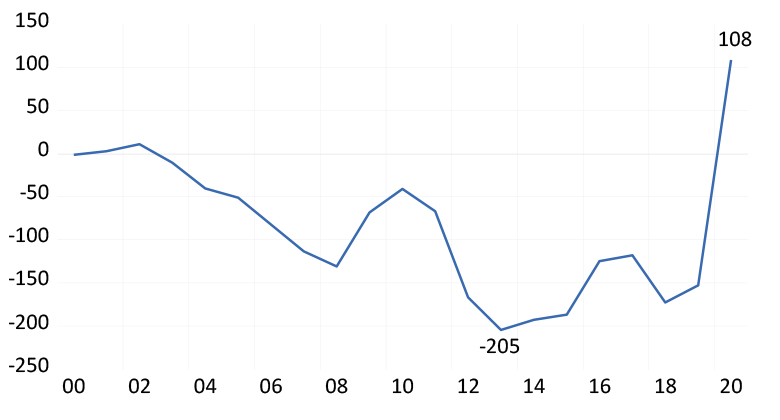

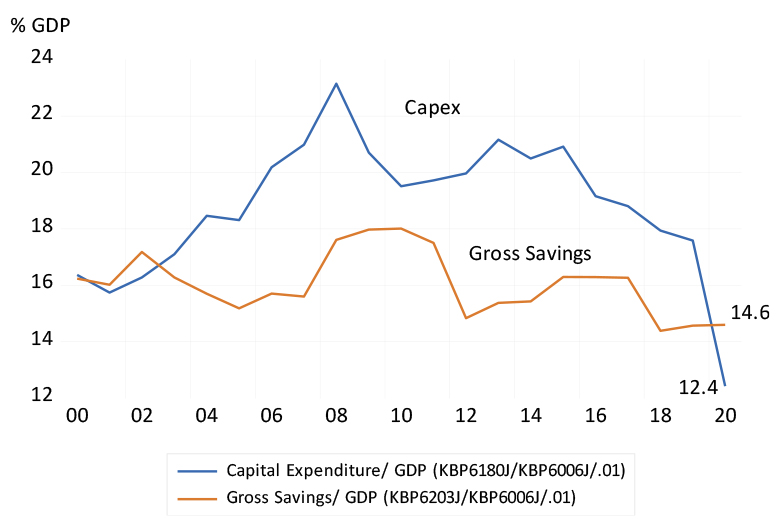

It has taken Covid-19 to bring the low rate at which South Africa saves above the dismal rate at which we are currently adding to plant and equipment, adding capital at the rate only of 12% of GDP in 2020. Accordingly, we have become a net lender to the world.

Reducing the risks of investing in SA will encourage more capital expenditure and savings in the form of earnings retained by business. We could then attract the necessary foreign capital at a lower cost than we are paying now. Reducing risks means sensibly reducing the threat of taking, not adding to it.

Source: SA Reserve Bank and Investec Wealth & Investment, 12/04/2021