Peter Bruce has pointed to something in the Stellenbosch water of the late sixties and seventies that produced so many rand billionaires. They would not have been inspired by some professor of economics enthusiastic about the power of free markets telling them to do good for the nation by getting rich. They are much more likely to have been told the opposite. Told why markets will not work nearly well enough and that any faith in entrepreneurial flair would be entirely misplaced. I have yet to meet a Stellenbosch economist who believes that an economy is best left guided by the forces of competition.

And one can perhaps understand why. The interventionist economic policies, long adopted in SA before 1994, clearly helped to completely transform the economic and educational status of the Afrikaner nation, in a generation, both absolutely and comparatively. They might have done even better with freer markets, but this would not have been self-evident. By every measure, the Afrikaner, on average lagged well behind the standards enjoyed by the average English speaker in the nineteen thirties. By the sixties they had caught up. Even, as the average incomes of both communities had improved significantly.

Many of the best and brightest Maties sought their futures working for the state and its agencies. The case for ownership by the state of some of the commanding heights of the economy, steel, electricity, railways and ports was taken as a given and not contended. And they were not, with few exceptions, seen as the path to private riches through corrupted procurement and biased tenders to which SOE’s are so conspicuously vulnerable. Nationalism and strong sense of community may have had something to do with this restraint.

Perhaps with Johan Rupert a fellow student, the example of the ineffable Anton Rupert was the inspiration. He who went door to door selling shares in his fledgling enterprise that was to take down a powerful near monopoly of the cigarette market in SA. The billions of the Stellenbosch cohort, like those of the Ruperts, were made in a conventional way. By competing successfully with established businesses for their customers and executing better combined with intelligent financial engineering that is always the leveraged and risky path to great wealth. Taking the opportunity provided by contestable markets is characteristic of successful, dynamic economies.

Peter Bruce is quite wrong to assert (Business Day July 27th) That Stellies route to billions is gone — and it’s undesirable. Apartheid-era billionaires can’t be reproduced in today’s democratic conditions.

It would be highly desirable were the South African economy to produce a few more billionaires in a similar old-fashioned way. By taking on established interests, winning market share and reviving businesses that have lost their way and are now valued at far below what can be regarded as their replacement cost. With the help of value adding, better designed financial structures and appropriate incentives for managers based on what really matters, return on all capital employed. It seems to me the opportunity to acquire great wealth in rands and dollars is as open, perhaps more open than it has ever been given current market pessimism.

The aspirant billionaire will not have to rob the taxpayer to get rich – though it is still unfortunately the most obvious route. Yet more than a few new billionaires are hard at work proving my point that Bruce may not have noticed from his rural retreat.

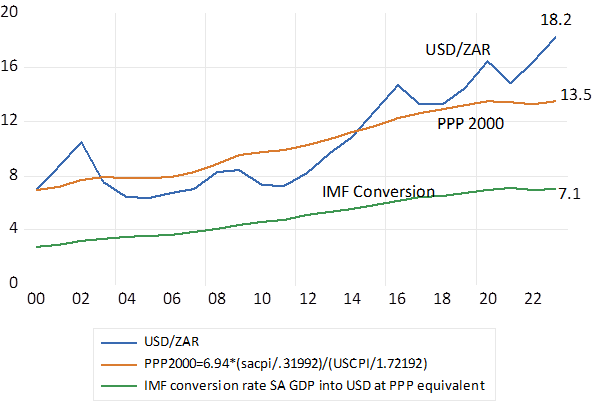

Though admittedly a billion rand today is a lower target, worth a lot less than a billion in 2000 – about 35% as much, after SA inflation. To compare purchasing power in US dollars, you might do as the IMF does – divide billions of rands by 7 not 19 to convert SA GDP into purchasing power dollar equivalents. If the rand just compensated for differences in SA and US inflation since 2000, a dollar would cost R13.5 and a billion rand would buy the equivalent of USD74m – more than nickels and dimes.

The exchange value of the Rand (USD/ZAR) and its purchasing power equivalent