Private sector involvement in South Africa’s key capital expenditure (capex) projects could be the catalyst to set off a virtuous cycle of investment and growth.

The Covid-19 lockdowns led to some unusual economic developments. Among them was that gross savings in South Africa came to exceed all declining expenditures on capital goods (new plant and equipment, new houses and apartments, etc). Thus, a “capital light” South Africa became an exporter of our scarce savings.

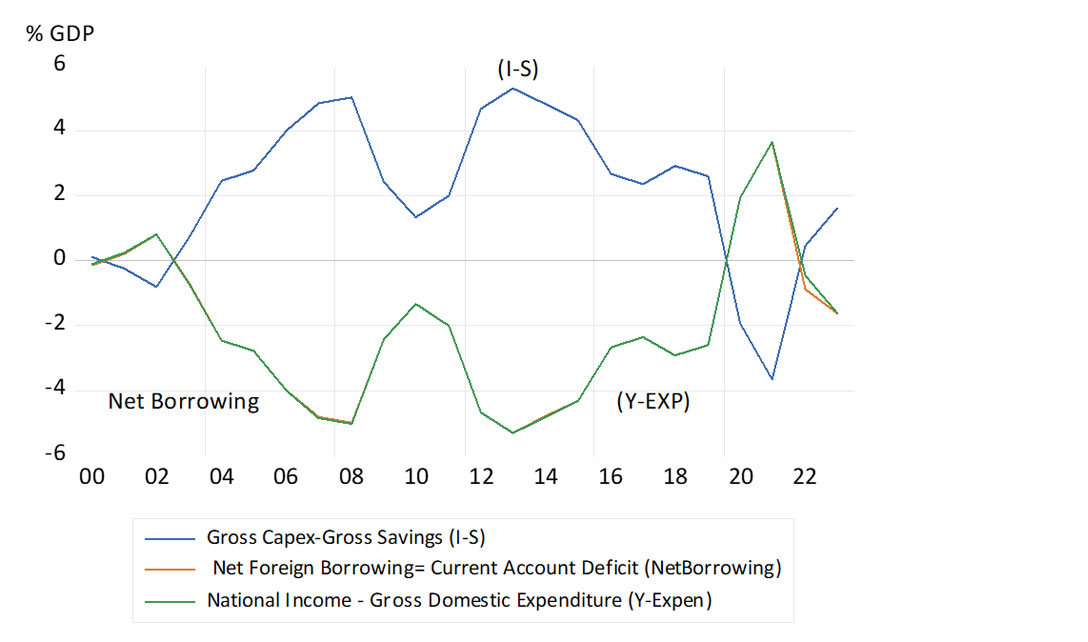

Last year normal service was resumed, capex increased by more than savings and South Africa became a net importer of foreign capital again. This “back to normal” state also meant that incomes fell short of all spending in 2023 and that the current account of the balance of payments went into deficit. All these deficits were equivalent to a modest 1.6% of GDP (see below).

SA national income and balance of payments – measured as a share of GDP

Source: SA Reserve Bank (national income and balance of payments accounts) and Investec Wealth & Investment, 09/04/2024

Is this good or bad news? Clearly, the more capital South Africa can attract from foreign savers – particularly if it were used to fund productivity and income-advancing plant and equipment, and R&D – the better the economy would perform in the short and long run. Or to put in another way, the higher the levels of gross spending, relative to current incomes, the larger the capital inflows and the larger the current account deficits.

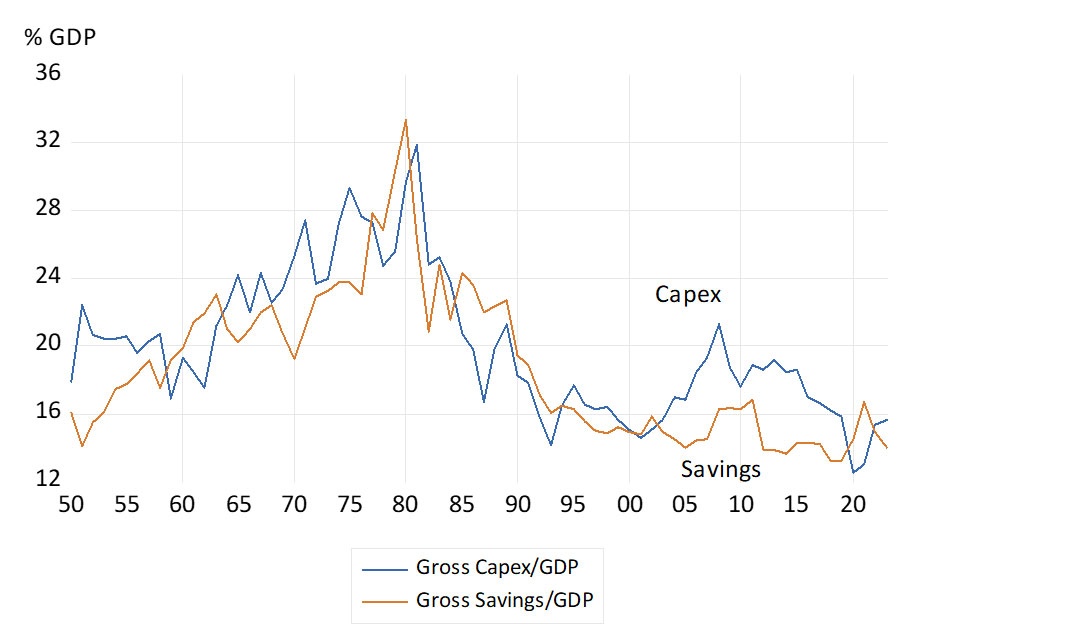

Yet both savings and capex have fallen to low proportions of total incomes. The savings and capex rates, now around 15% of GDP, have been in decline. Compare this with the strong growth years between 2002 and 2008, when capex again surged, the savings rate remained subdued, and foreign capital flowed in to realise faster growth (see below).

Gross capex and gross savings as a percentage of GDP

Source: SA Reserve Bank (national income and balance of payments accounts) and Investec Wealth & Investment, 09/04/2024

To achieve faster growth in incomes and expenditure, you need higher levels of capex. You also need South African households to spend more on the goods and services supplied by the local producers. Without support from interest-rate dependent household spending (now decidedly lacking), private businesses will not invest enough. Thus, any immediate increase in the savings rate (less spent) would neither be welcome nor realistic.

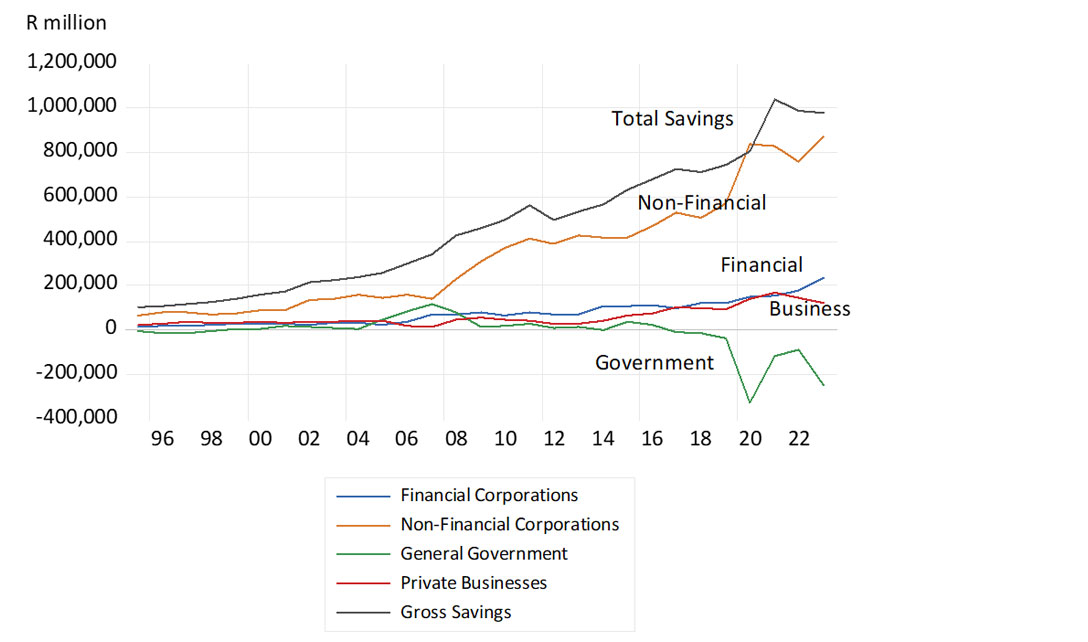

SA distribution of gross savings (R millions)

Source: SA Reserve Bank (production, distribution and accumulation accounts) and Investec Wealth & Investment, 09/04/2024

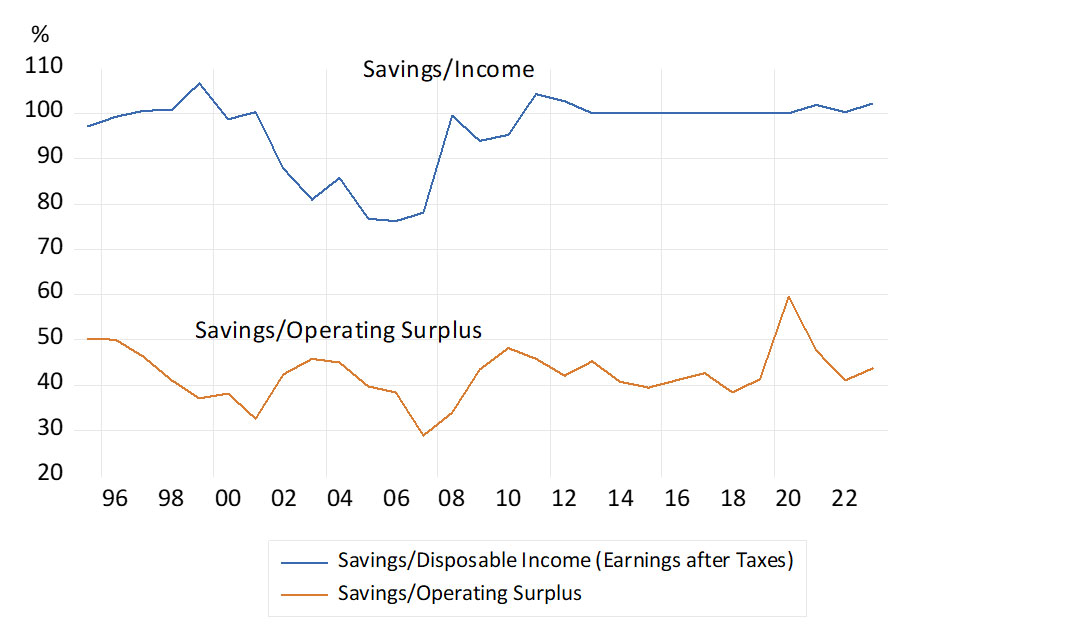

The extra debt raised by households to fund their homes, cars, furniture and appliances, largely cancels out their significant contributions to pension and retirement funds. This is why business savings (cash retained out of earnings) account for all of gross savings in South Africa. In the interest of faster growth for SA we would prefer businesses to spend more, to rely less on their own free cash flow, and augment their capex by raising debt or equity capital, including from abroad, as they did between 2002 and 2008. Negative free cash flow would be good for business and economic growth. As it was between 2002 and 2008 (see below)

But what would it take to set off for a virtuous cycle of more household spending and more profitable businesses, willing to raise their capex and labour forces, to then generate higher incomes for their workers?

SA corporation savings (cash retained) over disposable incomes (earnings after taxes)

Source: SA Reserve Bank (production, distribution and accumulation accounts) and Investec Wealth & Investment, 09/04/2024

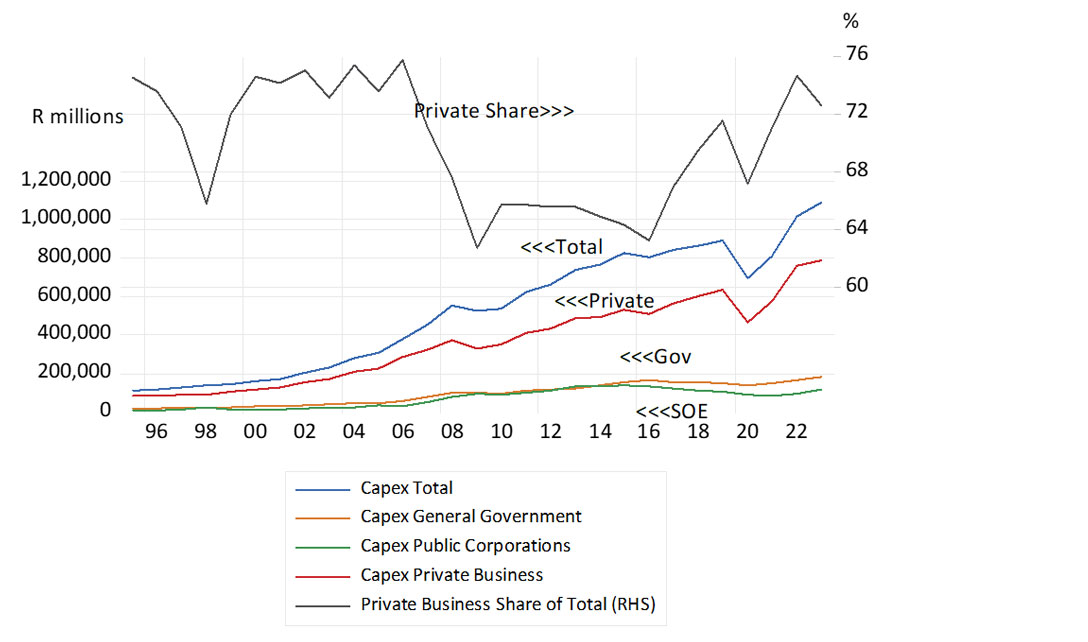

Much of the capex (over 70%) in South Africa is undertaken by private business enterprises. The share of the public corporations and the government in all capex has fallen away in recent years, (now 28%) after rising to well over 30% ten years ago. The Medupi and Kusile power plants and the Chinese locomotives were expensive projects that did not add to electricity generated or tonnes carried. It’s not enough to spend more on essential infrastructure, it must be capital well spent, to ensure the private sector can thrive.

SA gross capital expenditures (R millions) and share of private business in total capex (RHS)

Source: SA Reserve Bank and Investec Wealth & Investment, 09/04/2024

Eskom and Transnet have clearly failed the key economic survival test of earning a positive return on capital, as the government now recognises. The privately managed alternative is very much in prospect and the economic case for investing in South African infrastructure remains strong.

The private capital to fund such capex would be readily available from local and foreign sources. Private equity managers with access to institutional capital would be eager participants and the right terms to attract capital would not be onerous. These terms would have to guarantee inflation-linked utility charges, based on a realistic risk-adjusted return on the capital invested. Private business or private-public partnership so engaged would also need to be left largely free to sign their own procurement contracts. In this way, the virtuous circle would be set in motion.