Movements in the exchange value of the dollar itself explains the direction of emerging market exchange rates.

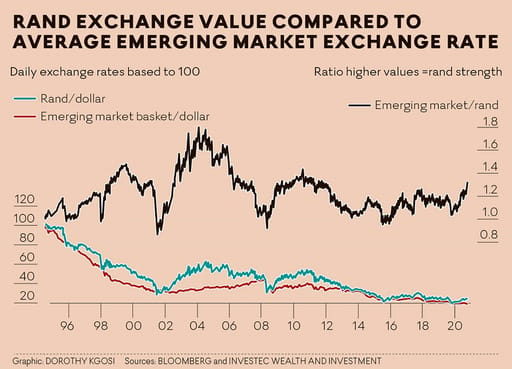

The daily dollar value of a rand has been closely tied to the value of other emerging market currencies ever since 1995, when SA opened up to global capital flows. When the ratio trends above or below the emerging market line the direction of the rand predictably reverts back to the average relationship of one to one. We have done no worse or better against the US dollar than the average emerging market economy.

Changes in SA-specific risks can help explain temporary differences between the rand and the other emerging market exchange rates, but more important is the force that has moved all such currencies, including the rand, in the same direction. The movements in the exchange value of the dollar itself explain the direction of emerging market exchange rates.

The greater difficulty is explaining the exchange value of the dollar. The problem for all businesses that trade globally is that the exchange value of the dollar itself is highly variable. However, it too has had a strong tendency to revert to square one relative to other developed market exchange rates, though the time taken varies.

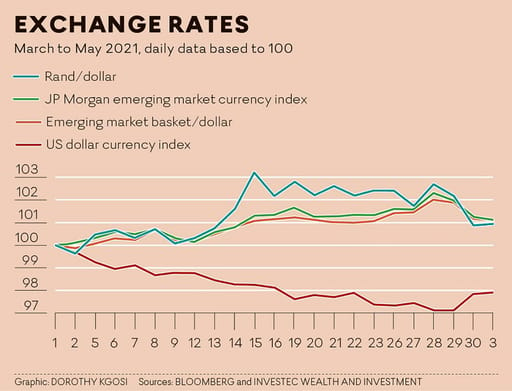

The behaviour of the rand since March conforms well to these forces. The dollar weakened until very recently, emerging market currencies gained ground, and the rand did a little better than the average emerging market until late April, after which it has moved back into line.

Compared with a year ago these exchange rate movements are dramatic. The US dollar index (DXY), a measure of the value of the dollar relative to a basket of other currencies, is down 8%; the rand has gained 23% against the dollar; and the average emerging market currency is now worth about 6% more than the dollar.

The rand appears to be a high beta exchange rate. It does worse than the average in more difficult times, as it did during the global financial crisis, and does relatively well after the crisis appears to have been resolved, as has been the case since the global lockdowns.

The SA government pays more than 2% more per annum to borrow dollars for five years than does the US, because of doubts about our fiscal responsibility. The accordingly high cost of capital discourages the capital expenditure by private business that is so necessary for faster growth.

Yet something is stirring to improve the outlook. Much higher metal prices are boosting SA incomes and tax revenues. Higher growth rates in nominal GDP and tax revenues will improve the critical debt-to-GDP ratio. Sticking firmly to government expenditure targets will further improve our fiscal reputation and help reduce the risk premium. The future is in our own hands (partly at least), not only written in the stars.