The bond market indicates that inflation is expected to stay below 2% per annum over the next ten years in the US. And the Fed is confidently expected not to raise short term rates this year.

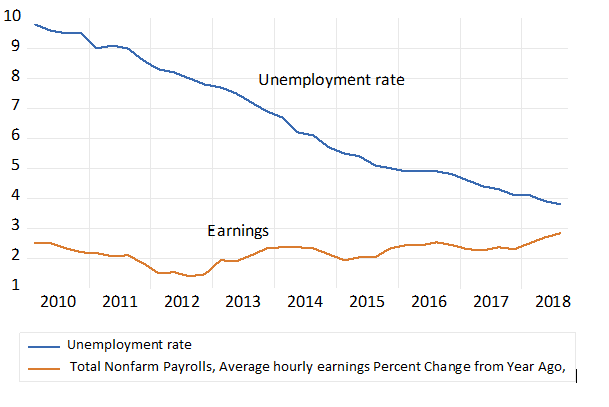

Are such views consistent with a very buoyant labour market? Unemployment rates are below 4% while average earnings are rising at about 3% p.a. Some believe this portends more inflation and higher interest rates that will confound the market consensus.

U.S. Unemployment rate and growth in earnings

Source; Fred- Federal Reserve Bank of St.Louis and Investec Wealth and Investment

Do changes in prices lead or follow changes in wage rates in the US? The economic reality is that they both follow and lead with variable lags. The markets for goods and the markets for labour have the general state of the economy in common. The wages and prices that emerge depend upon how rapidly the demand for and the supply of all goods, services and labour are growing. Higher or lower prices, wages and asset valuations have their causes and in turn will have effects on the willingness to buy or sell. And might not higher real wages in the US soon reduce the demand for labour and employment – as they have done in SA?

The prices of goods and services are not simply determined by adding a constant percentage point to the cost of producing them. The state of the economy (demand) and the competition to supply customers (including from abroad) will determine how much margin over costs finds its way into the prices a firm will charge. It is this mix of demand pull and cost push and pressures on margin that determines prices.

Another force common to both is the increase in prices and wages expected in the future. The faster they are expected to increase the more workers and firms and investors will wish to charge upfront for their services.

The Phillips curve predicts that decreases in the unemployment rate (increases in the demand for labour) will cause wages to rise faster. Keynesian economists invoked this theory in the sixties to argue that more employment could be traded of for more inflation that comes with higher wages. The idea was that workers, unwilling to accept the wage cuts that might have restored full employment, might be fooled into accepting lower real wages by inflation.

The theory has had very poor powers of prediction- particularly in the high inflation and slow growth seventies. It became a case of more inflation and slower growth and still is. Firms and workers and the unions that negotiate for them have every reason to build inflation into their wage and price settings. Therefore only inflation surprises therefore can have real effects on the economy- not inflation itself.

And the market place is not easily surprised. Their inflation forecasts, using very similar methods, are as likely to be accurate or rather as inaccurate as those of the central banks. There is no good reason to believe that any wage plus theory of inflation will beat the market view on inflation today.

Central bankers have long recognized that there was no output or employment benefit to be gained from tolerating more inflation. Only unexpectedly higher inflation might stimulate more output- but the ability of monetary policy to helpfully surprise the market is very limited. Central bankers now judge it better to avoid inflation surprises in both directions. Better they believe to offer the market place a highly predictable and low rate of inflation in the interest of balanced and permanently higher growth rates- as does the SA Reserve Bank.

Yet balanced growth demands more flexibility than the SA Reserve Bank has demonstrated. The flexibility to recognize that powerful and possibly frequent supply side shocks to inflation – exchange rate, oil price and food price shocks – do not call for higher interest rates. Central banks can hope to stabilize aggregate demand – supply management is beyond their compass. And the market place is fully capable of recognizing the difference. Inflationary expectations are also rational.