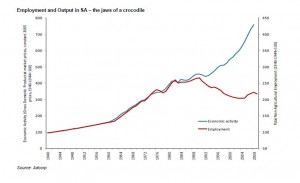

The employment problem in SA has become a major focus of government action. Employment in the formal sector, that is with employers who provide medical and pension benefits and collect PAYE , has lagged well behind GDP growth since the mid 1990s.

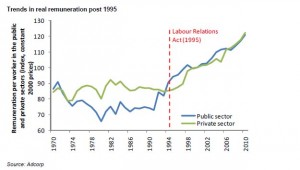

Furthermore real remuneration per worker since then has increased significantly over the same period. The two figures below, provided by Adcorp, tell the full story of much better jobs for far fewer workers. The SA economy, or at least the formal part of it, has become much less labour intensive, and much more capital and skilled labour intensive. Decent jobs, but only for the fortunate few, is the SA reality.

The less fortunate or less well endowed with skills get by finding work outside the recorded regulated sector and depend increasingly on welfare grants. Immigrants, of whose large numbers we are uninformed about, without cash grants support from the SA government (i.e. the taxpayer) seem to find work easily enough, though no doubt at highly competitive wages.

Click figures to see full size

For any economist who takes market forces as well as prices, wage and employment data seriously, the conclusion is obvious enough. It was the Labour Relations Act, uniform minimum wages and all the other many protections accorded to workers with jobs and the correspondingly extra burdens placed on employers after 1995 that have made employing labour more expensive. The result has been that fewer young, unskilled and unproven workers have been hired by established businesses. Substitution towards more skilled and more experienced workers, supplied with better equipment, has been the obvious economic response made by many firms.

The government would seem to accept this argument. However rather than introduce more flexibility into the labour market directly by relieving regulation and letting potential employers and employees get on with the job, especially in rural areas, the intention is instead to subsidise employment with tax relief for employers on a large expensive scale. No doubt the government itself and its subsidiaries will also be commanded to provide more jobs. Clearly Cosatu, representing established workers, stands in the way of the economically obvious, but politically inconvenient solution.

The old adage applies that if you want more of something subsidise it and if you want less of something tax it. No doubt throwing tax payers money at the employment problem will increase some forms of employment.

But what will the presumably higher taxes needed to cover these subsidies do to other forms of employment? The hope must be that lower income taxes for companies hiring more labour and paying less tax or receiving cash subsidies, will be offset by consumption rather than higher income tax rates for companies or individuals. SA will not benefit from raising tax rates on companies or their skilled workers. The supply of capital and skills to the SA economy needs to be encouraged not discouraged. And more capital and skills made available increases the demand for unskilled labour.

The employment and income problems can be solved in the old fashioned way – by allowing freedom to hire and be hired and to fire when performance on the job is inadequate. It can also be solved with the aid of greater freedom for entrepreneurs to compete with the established firms, using labour, rather than capital intensive methods.

A free labour market means more jobs and faster economic growth that over time makes for shortages of labour and higher standards of living for all, even the least skilled. The Chinese seem to know all about the improvements in standards of living that come from flexible labour markets that absorb labour on a large scale and provide much improved remuneration over time. SA could learn from China.

The grave danger for SA is that it should become more like an Egypt with over a third of all employment provided by the state in one or other form. The trouble with the state as an employer is that while it can provide jobs (paid for by the taxpayer) it is most unlikely to increase the productivity of its work force. And its work force will be encouraged to interfere with the economic potential of private firms.

This general lack of productivity, with so much labour employed by the government, leads to slow economic growth, minimal improvements in output and incomes and to the great frustration of the work force and potential workers. It becomes especially frustrating when the only decent jobs available become those supplied by the state (often corruptly) that a hard pressed tax base finds increasingly difficult to provide for on attractive terms.

One can only hope that the government recognises that the solution can only be found with a strong dose of economic realism. Such realism alas still seems to be wanting, with pie in the sky employment projections the order of the day. Brian Kantor

Continue reading the full Daily View for 11 February here: Mubarak on the banks of denial