We are well aware that slow economic growth depresses the growth in tax revenues. What is not widely recognised is the influence that tax rates and taxation have on economic growth. The burden of taxation on the SA economy, measured by the ratio of taxes collected to GDP, has been rising as GDP growth has slowed down, so adding to the forces that slow growth in incomes and taxes.

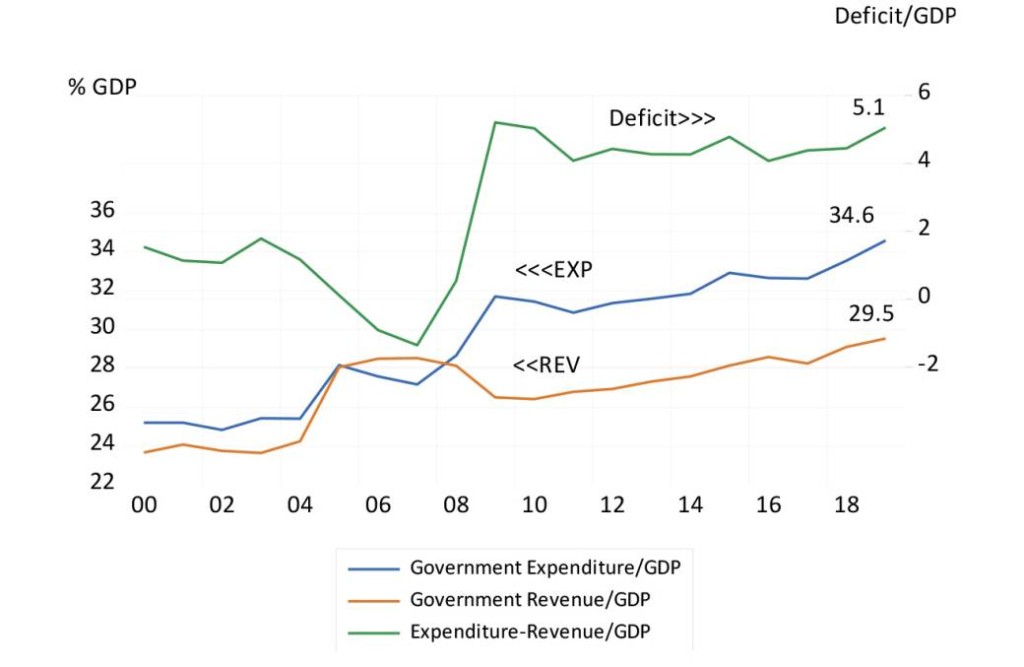

Trends in government revenue, expenditure and borrowing

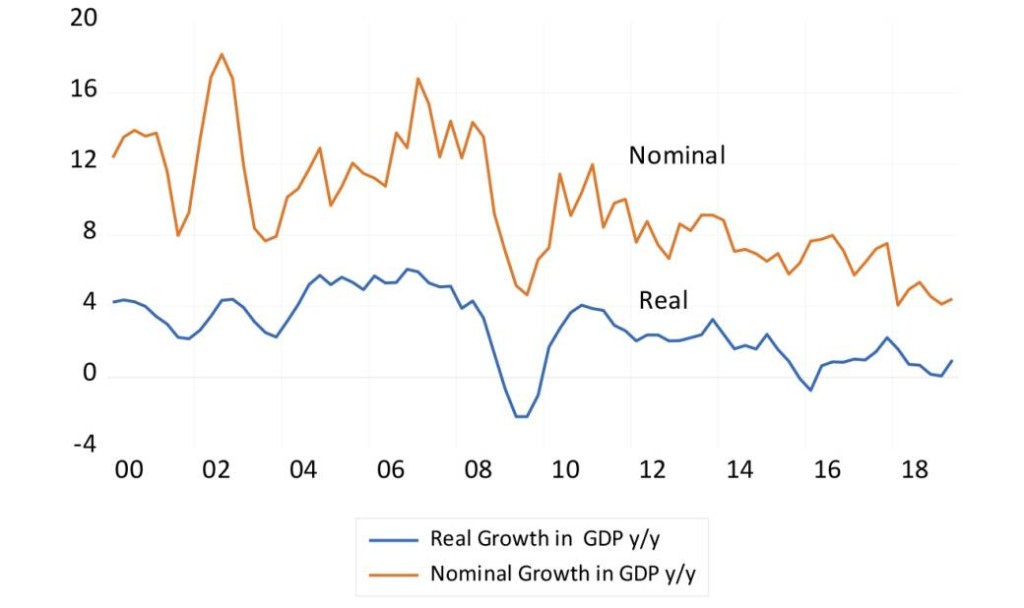

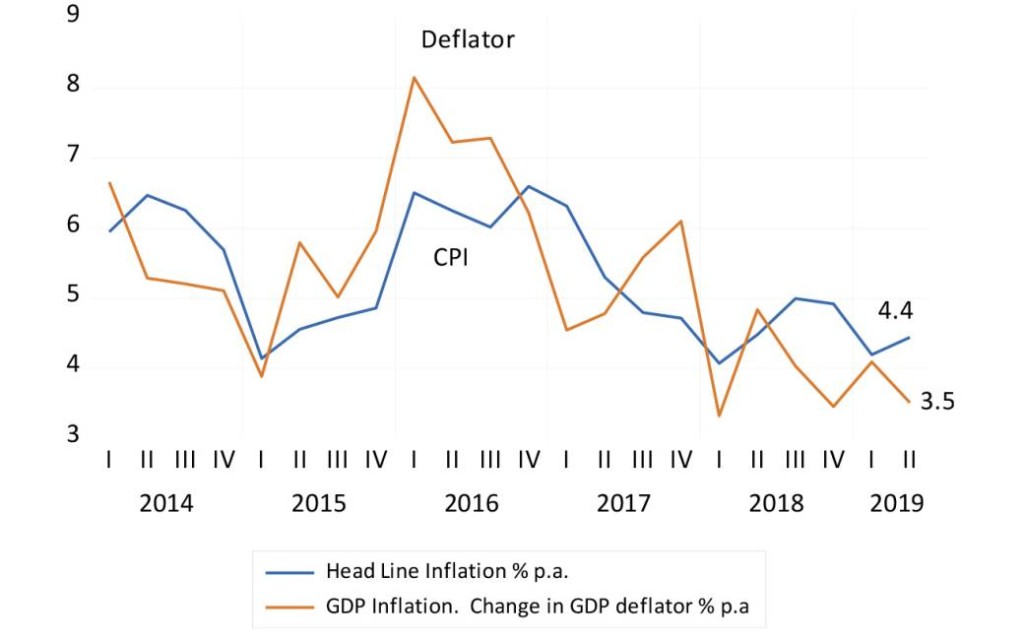

The GDP growth rate picked up in Q2 2019. But GDP is only up 1% on the year before while in current prices, it has increased by only 4.4%. That is slower nominal growth than at any time since the pre-inflationary 1960s, which is not at all helpful in reducing debt to GDP ratios (something of great concern to the credit rating agencies). This 4.4% growth is a mixture of the slow real growth and very low GDP inflation, now only about 3.5% a year.

Annual percentage growth in real and nominal GDP

GDP and CPI inflation

In the first four months of the SA fiscal year (2019-2020) personal income tax collected grew by an imposing 9.7% or an extra R14bn compared to the same period of the previous financial year. Higher revenues from individual taxpayers was the result of effectively higher income tax rates, so-called bracket creeps, on pre-tax incomes that rise with inflation.

Income tax collected from companies, however, stagnated, while very little extra revenue was collected from taxes on expenditure. Lower disposable incomes resulted in less spending by households and the firms that supply them. The confidence of most households in their prospects for higher (after-tax) incomes in the future has been understandably impaired.

Treasury informs us that total tax revenue this fiscal year, despite higher income tax collected, is up by only 4.8%, compared to the same period a year ago, while government spending has grown up by 10.3%, or over R51bn. The much wider Budget deficit of R33bn (Spending of R156.6bn and revenue of R123.6bn) represents anything but fiscal austerity. It has added to total spending in the economy, up by a welcome over 3% in Q2 2019 – after inflation.

But deficits of this order of magnitude are not sustainable. Nor can they be closed by higher income and other tax rates that would continue to bear down on the growth prospects of the economy and the tax revenues it generates. A sharp slowdown in the growth of spending by government, combined with the sale of loss-making and cash-absorbing government enterprises is urgently called for if a debt trap is to be avoided. Given that the debts SA has issued are mostly repayable in rand, rands that we can print an infinite amount of, a trip to the IMF and the “Ts and Cs” they might impose on our profligacy is unlikely.

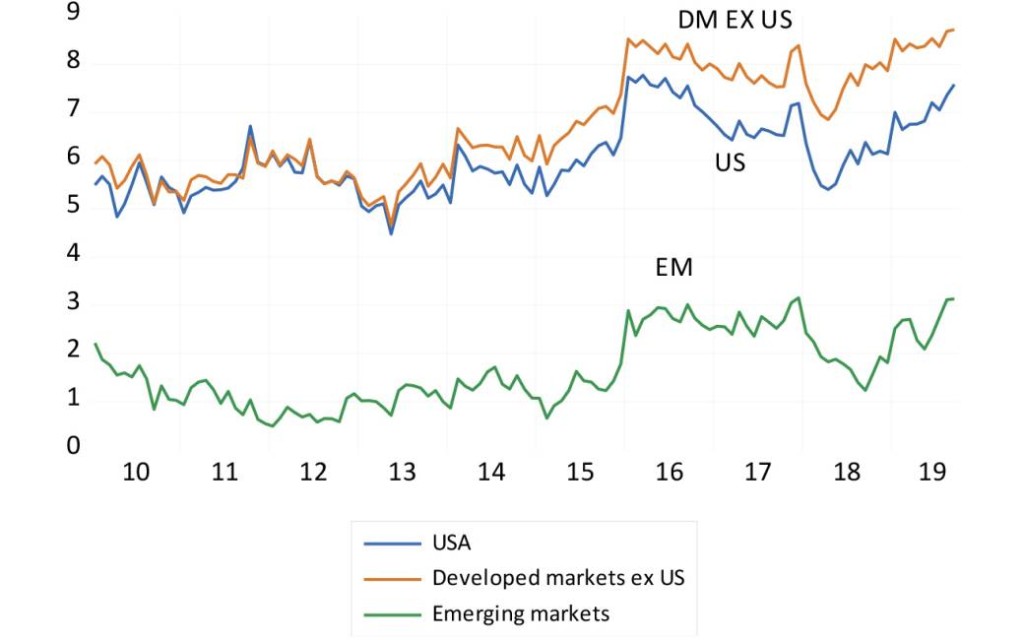

More likely is a trip to the printing press of the central bank rather than the capital markets to fund expenditure. Such inflationary prospects are fully reflected in the interest we have to pay to fund our deficits. These interest payments add significantly to government spending. The spread between what the SA government has to offer lenders and those offered by other sovereign borrowers has been widening.

The SA government now has to pay 8.7 percentage points a year more in rands than the average developed market borrower, ex the US (Germany and Japan included) and 7.6 percentage points a year more than the US has to offer for long-term loans. We also have to pay 3.1 percentage points a year more than the average emerging market borrower has to pay to borrow in their own currencies.