The mood may have changed even if the SA economic facts have not. But the Moody’s negative watch can do SA good without doing any harm.

Moody’s has raised legitimate concerns about the risks facing economic policy makers in SA that will resonate strongly with observers not only outside but also inside government circles. The question one would have to ask is what is especially new about these threats to SA political and economic stability. Perhaps the Moody’s decision to put SA’s credit rating on negative watch tells us more about the changing world of credit and especially for credit rating agencies than it is does about the direction of SA economic policy. What is clearly especially galling to the Treasury is that Moody’s appears to have been unimpressed by the strong affirmation of the conservative fiscal policy settings outlined by Finance Minister Gordhan in his speech to Parliament in October backed up in his recently issued Medium Term Budget Policy Statement. The government has planned to maintain the ratios of government revenue and government expenditure to GDP, to reduce debt to GDP ratios and to give greater impetus to capital formation rather than improved benefits for those who work for or depend on government.

The populist threats to the conservative setting of fiscal policy or the all-important role played in the economy by privately owned businesses, both domestic and foreign, are not new and will remain an ever present in SA, as they will almost everywhere else (Switzerland perhaps excepted and Wall Street Masters of the Universe not excluded) . The greatest risk to stability in SA is slow rates of economic growth that frustrate ambitions of individuals and firms and the financial capacity of the public and private sectors. This can lead to attempts at quick fixes by politicians.

The rating agencies have long been very well aware of these dangers to the impressive conservative fiscal and monetary policy directions taken by the new SA. Aware enough, that is, to have made SA’s ascent to an investment grade credit status a long hard ride. It is this status that has now been put on negative watch by Moody’s (though not by Standard and Poor’s). But Moody’s was not entirely negative in its judgment. It did not derate RSA credit, for the following reasons as we quote below from its statement:

“To date, South Africa’s fiscal picture and economic policy parameters have remained generally in line with Moody’s expectations, hence the continued A3 rating. The South African authorities’ economic stewardship has been effective for more than a decade, during which time they brought public finances and inflation under control and significantly bolstered the country’s external liquidity position. In addition, meaningful progress has been made in raising living standards, expanding social services and physical infrastructure, and putting in place a financial support mechanism for the most underprivileged. Finally, the outlook for South Africa’s public finances has not diverged significantly from Moody’s projections when the country entered into recession in 2009, roughly the time of Moody’s last sovereign rating action, despite the rather sluggish economic recovery over the past two years….”

The Moody’s rationale for a negative watch on RSA credit went as follows and is highly deserving of serious attention especially by those in the tripartite alliance inclined to believe in quick fixes or the magic wands that are meant to provide well paid jobs for all (that current policies applied to regulate the SA labour market have so singularly And conspicuously failed to do), a fact of SA economic life well recognized incidentally by Minister Gordhan in his policy review.

To quote the rationale:

“The primary driver behind Moody’s decision to change the outlook on South Africa’s government ratings to negative is the rising pressure from society at large, as well as from within the ANC and its political partners, to ease fiscal policy in order to address South Africa’s high levels of poverty and unemployment. In Moody’s view, spending beyond the substantial amounts already budgeted in response to such demands could push debt to levels more commensurate with lower-rated sovereigns. South Africa’s direct debt and guarantees for state-owned companies’ obligations currently approach or exceed 50% of GDP. Moreover, a substantial proportion of the government budget is already absorbed by wages, social support and debt service, limiting the room for new growth-supportive spending.

“Secondly, Moody’s is concerned that economic growth will be somewhat slower than previously expected in the years ahead due to a weaker global economy, depressing any rebound in South African employment levels over the coming years. This would in turn aggravate existing frustrations over the lack of economic opportunities. Moreover, job creation in this environment would not be enough to absorb new entrants to the labour force nor reduce the already high levels of unemployment. In Moody’s opinion, this situation poses risks to political stability over the longer term. Thirdly, Moody’s believes that the political leadership’s unwillingness to definitively reject demands from certain segments of the political spectrum for more activist policy interventions is harmful to South Africa’s economic prospects, in particular private investment. The agency also says that nationalisation of the mines and/or other sectors — however unlikely to happen — would not achieve the stated aim of accelerating progress on black economic transformation. Instead, such moves are more likely to do the opposite, reducing the country’s attractiveness to both local and foreign investors, and encouraging the outward migration of citizens and businesses. Such actions would in turn raise the risk premium on government debt, further inflating the already-rising costs of debt service. Overall, Moody’s believes that the next two years will be especially challenging for South Africa’s political system, with the potential for further pressures emerging for the established economic policy framework during this period.”

The most important factor restraining growth in SA over the next 12 months are not the structural weaknesses of the SA economy or the populist threat to property rights and fiscal policy settings. It is the European government debt crisis and the threat it poses to global growth and sothe demand for SA goods and services, including services supplied to tourists. The behaviour of the rand and so the outlook for inflation and its impact on interest rates paid on debt issued by the RSA is completely dominated by these global forces. RSA specific political or monetary policy influences on these important influences on the growth outlook and the willingness of SA firms and households to invest or spend are conspicuously absent. It is not the Moody’s watch that moved the rand yesterday but higher yields on Italian government debt.

Hopefully these facts of economic life have been well appreciated at the Reserve Bank sitting today to decide on the repo rate. As the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) of the Bank pointed out in its latest statement, the SA economy is being held back by a lack of foreign and domestic demand. The short term outlook for the global economy has deteriorated. The outlook for the domestic economy is not conspicuously improved, at least according to Moody’s. The Reserve Bank can only hope to stimulate domestic demand by lowering interest rates. It cannot expect to have any predictable influence on foreign demand or the value of the rand (and so on the outlook for inflation) with its interest rate settings.

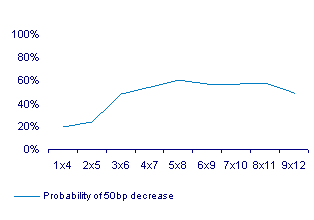

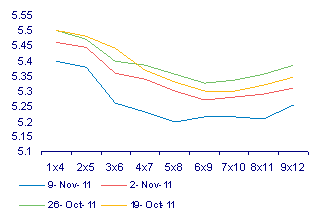

That lowering interest rates might do some good in promoting essential economic growth and so reducing SA risks (without doing any harm in the form of more inflation) should make a decision to cut interest rates an obvious one. If it was not altogether obvious at its last September meeting, it should be obvious today. And the Moody report would, it may be hoped, have made it even more obvious: the risks to the SA economy are not inflation (over which the Reserve Bank has no influence in the short term) but to growth, over which interest rate settings may have some influence. However the market place yesterday was not expecting a 50bps cut. This is despite the short term Forward Rate Agreements having shifted significantly lower over the past week, raising the probability of a 50bps cut to over 50% within three months. The probability of a cut today was still only about 20%.

We can hope the Reserve Bank will get it right and that the market has misread its better intentions. Brian Kantor