The latest twist to the euro debt crisis has come in the form of US money market funds withdrawing cash from European banks. However the European Central Bank (ECB) can print all the cash the banks may require – in exchange for collateral (including European government’s sovereign debt) provided by banks – to replace the deposits lost by the European Banks. This process is well under way.

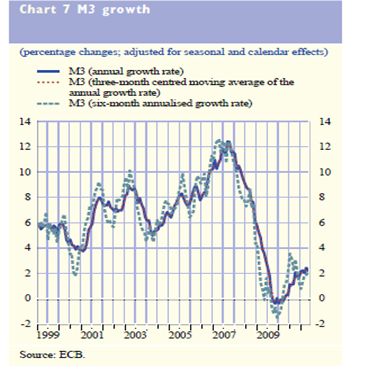

The ECB in its latest August Monthly Review editorial said that there was “ample liquidity” in the system; enough to keep the ECB still explicitly worried about inflation (amazingly so). Besides indicating its almost ritual concerns about inflation, the editorial also discusses the liquidity supplementing actions under way. To quote the editorial: “While the monetary analysis indicates that the underlying pace of monetary expansion is still moderate, monetary liquidity remains ample and may facilitate the accommodation of price pressures.”

Reference is also made in the editorial to the large and unusual steps that are being taken to add liquidity to the system. To quote the ECB again: “As stated on previous occasions, the provision of liquidity and the allotment modes for refinancing operations will be adjusted when appropriate, taking into account the fact that all the non-standard measures taken during the period of acute financial market tensions are, by construction, temporary in nature…”.

A primary task of any central bank is to save the financial system from imploding for want of liquidity (cash) – caused by a run on the banks – by providing liquidity that it can create without any cost. The withdrawal of US money market funds from Euro banks may be regarded as such a run which could engulf all European banks if it is allowed to degenerate into some kind of panic. This would affect even those banks with strong balance sheets.

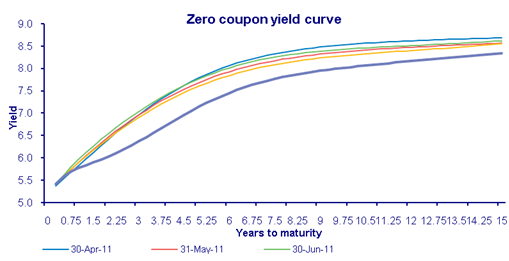

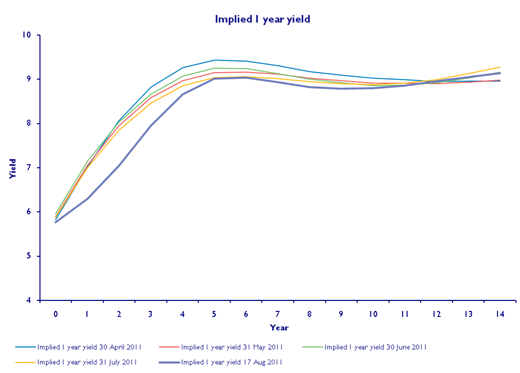

Only the ECB has the power to print euros to support the system (the other national central banks tied to the euro no longer have this power). If these other central banks were not constrained by fixed exchange rates to the euro they would be printing money to save their own banks; and if they could there would be no sovereign debt crisis, only an inflation danger. Yet despite QE1 and QE2 and vast amounts of cash injected into the US financial system (that saved it from imploding) the danger of US inflation remains a very distant one, as indicated by very low yields on US Treasury Bonds. The low yields on German bonds indicate the same and make the ECB’s concerns with inflation given the current uncertainties seem otiose. It should be encouraging to those anxious about the future of European banks, their sovereigns and the euro that current spreads on Italian and Spanish government bonds have declined from well over 6% and stabilised around the 5% level. Any downward move in these yields would be comforting; any significant move higher would add to anxieties.

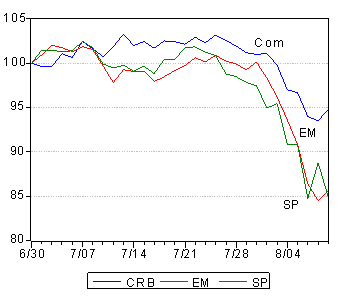

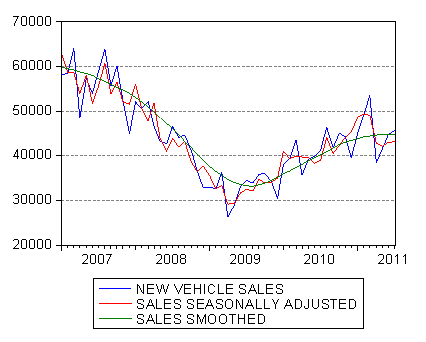

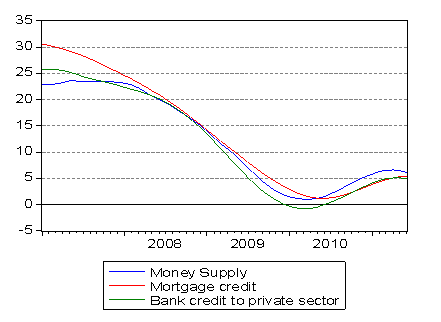

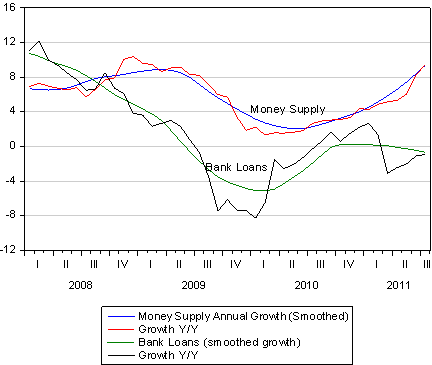

The ample liquidity that the ECB refers to is taking the form of increases in the deposits the Euro banks are holding with their central banks. Like their US counterparts the banks in Europe are holding cash in excess of their legal reserve requirements though, as in the US, not enough cash to prevent the European money supply, broadly defined, from growing. Though, as we show in the chart below, this money supply growth may be slowing down in Europe while picking up in the US. This pick up in money supply growth rates, despite little growth in bank lending, is very welcome and not consistent with a recession.

The question is asked as to why European banks are now valued at considerably less than the value of their books. The answer is that it is only partly to do with the crisis of confidence in the survival prospects of the banks themselves. The quality of the assets on the books of the banks, including sovereign debt, is suspect. Also, the banks are holding more cash earning very little or no interest income, implying lower earnings to come. Furthermore, of perhaps greater significance for the value of banks, the European banks will have to or be required to raise additional capital to secure their futures. The capital may come from the market or, if shareholders are not forthcoming, from their governments. The earnings outlook for European banks is not promising. They will survive – but may not be able to generate returns on capital that justify any premium to book value.