Ben Bernanke has now retired as Fed chairman, having rewritten the book on central banking.

He has done this not so much by what he and his fellow governors (including his successor Janet Yellen) did to address the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) that erupted in 2008, but by the enormous scale to which he supplied cash to the US and global financial system as well as in injecting new capital to shore up financial institutions whose failure would pose a risk to the financial system.

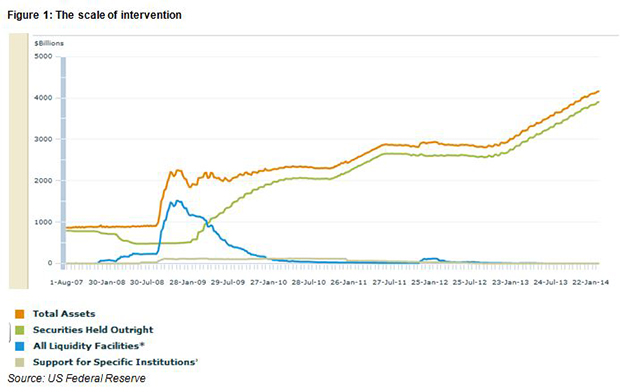

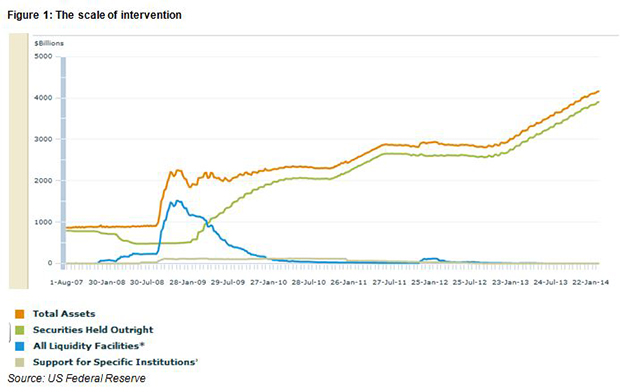

The scale of Fed interventions in the financial markets is indicated in the figure below which highlights the explosive growth in the asset side of its balance sheet. The initial actions taken after the collapse of Lehman Brothers in September 2008, what may be regarded as classical central bank assistance for a financial system in a crisis of liquidity, was superseded by further massive injections of cash into the US and global financial system as the figure makes clear. The cash made available by the central bank in exchange for securities supplied (discounted) by hard pressed banks, when only cash would satisfy depositors and other lenders to banks, alleviated the panic and allowed normally sound financial institutions to escape the run for cash. But Quantitiative Easing (QE) thereafter became much more than a temporary help to the financial system.

Chairman Bernanke recently took the opportunity to explain his actions and the reasoning behind them in a valedictory address to his own tribe (that of professional economists) gathered at the annual meeting of the American Economic Association (AEA) in early January 20141. On the role of a central bank in a financial crisis, he said:

“For the U.S. and global economies, the most important event of the past eight years was, of course, the global financial crisis and the deep recession that it triggered. As I have observed on other occasions, the crisis bore a strong family resemblance to a classic financial panic, except that it took place in the complex environment of the 21st century global financial system. Likewise, the tools used to fight the panic, though adapted to the modern context, were analogous to those that would have been used a century ago, including liquidity provision by the central bank, liability guarantees, recapitalization, and the provision of assurances and information to the public.”

Furthermore:

“The Federal Reserve responded forcefully to the liquidity pressures during the crisis in a manner consistent with the lessons that central banks had learned from financial panics over more than 150 years and summarized in the writings of the 19th century British journalist Walter Bagehot: Lend early and freely to solvent institutions. However, the institutional context had changed substantially since Bagehot wrote. The panics of the 19th and early 20th centuries typically involved runs on commercial banks and other depository institutions. Prior to the recent crisis, in contrast, credit extension …….. Accordingly, to help calm the panic, the Federal Reserve provided liquidity not only to commercial banks, but also to other types of financial institutions such as investment banks and money market funds, as well as to key financial markets such as those for commercial paper and asset-backed securities. .Because funding markets are global in scope and U.S. borrowers depend importantly on foreign lenders, the Federal Reserve also approved currency swap agreements with 14 foreign central banks.

“Providing liquidity represented only the first step in stabilizing the financial system. Subsequent efforts focused on rebuilding the public’s confidence, notably including public guarantees of bank debt by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation and of money market funds by the Treasury Department, as well as the injection of public capital into banking institutions. The bank stress test that the Federal Reserve led in the spring of 2009, which included detailed public disclosure of information regarding the solvency of our largest banks, further buttressed confidence in the banking system.”

In the accompanying notes to his speech, the following explanations of shadow banking as well as the special arrangements made to boost liquidity were specified as follows:

“Shadow banking, as usually defined, comprises a diverse set of institutions and markets that, collectively, carry out traditional banking functions–but do so outside, or in ways only loosely linked to, the traditional system of regulated depository institutions. Examples of important components of the shadow banking system include securitization vehicles, asset-backed commercial paper conduits, money market funds, markets for repurchase agreements, investment banks, and nonbank mortgage companies.

“ Liquidity tools employed by the Federal Reserve that were closely tied to the central bank’s traditional role as lender of last resort involved the provision of short-term liquidity to depository and other financial institutions and included the traditional discount window, the Term Auction Facility (TAF), the Primary Dealer Credit Facility (PDCF), and the Term Securities Lending Facility (TSLF). A second set of tools involved the provision of liquidity directly to borrowers and investors in those credit markets key to households and businesses where the expanding crisis threatened to materially impede the availability of financing. The Asset-Backed Commercial Paper Money Market Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility (AMLF), the Commercial Paper Funding Facility (CPFF), the Money Market Investor Funding Facility (MMIFF), and the Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility (TALF) fall into this category.”

The initial injections of liquidity by the Fed to deal with the crisis was followed by actions that did write a further new page to the central bankers’ play book. That is, in the form of very large and regular additional injections of additional cash into the financial system, made on the Fed’s own initiative, in the form of a massive bond and security buying programme, which accelerated in late 2011 and early 2013 (QE2 and QE3) that was undertaken not so much to shore up the financial system that had stabilized, but undertaken as conventional monetary policy to influence the state of the economy by managing key interest rates and especially mortgage rates.

Usually, monetary policy focuses on changes in short term interest rates, leaving long term interest rates and the slope of the yield curve to the market place. But in the US, the mortgage rate, so important for the US housing market, is a long term fixed rate of interest linked to long term interest rates and US Treasury Bond Yields. These long term fixed mortgage rates (30 year loans) available to homeowners are made possible only with the aid of government, in the form of the government sponsored mortgage lending bodies Fannie Mae and Freddy Mac, whose lending practices did so much to precipitate the housing boom and bust and were particularly in need of rescuing by the US Treasury. Their roles in the crisis do not feature in the Bernanke speech made to the AEA.

The state of the US housing market is a crucial ingredient for improving the state of US household balance sheets that are so necessary if households are to spend more in order that that the US economy can recover from recession. Households account for over 70% of all final demands in the US and only when households lead can firms be expected to follow with their own spending plans. These household balance sheets had been devastated by the collapse in house prices, by 30% on average from the peak in 2006 to the trough in average house prices in 2011. It was this boom in house prices followed by a collapse in them that was the proximate cause of the financial crisis itself.

This bubble and bust, after all, happened on Bernanke’s watch as a governor and then as chairman of the Fed, for which the Fed does not take responsibility. A fuller explanation of the deeper causes of the GFC was offered by Bernanke in his speech to the AEA:

“The immediate trigger of the crisis, as you know, was a sharp decline in house prices, which reversed a previous run-up that had been fueled by irresponsible mortgage lending and securitization practices. Policymakers at the time, including myself, certainly appreciated that house prices might decline, although we disagreed about how much decline was likely; indeed, prices were already moving down when I took office in 2006. However, to a significant extent, our expectations about the possible macroeconomic effects of house price declines were shaped by the apparent analogy to the bursting of the dot-com bubble a few years earlier. That earlier bust also involved a large reduction in paper wealth but was followed by only a mild recession. In the event, of course, the bursting of the housing bubble helped trigger the most severe financial crisis since the Great Depression. It did so because, unlike the earlier decline in equity prices, it interacted with critical vulnerabilities in the financial system and in government regulation that allowed what were initially moderate aggregate losses to subprime mortgage holders to cascade through the financial system. In the private sector, key vulnerabilities included high levels of leverage, excessive dependence on unstable short-term funding, deficiencies in risk measurement and management, and the use of exotic financial instruments that redistributed risk in nontransparent ways. In the public sector, vulnerabilities included gaps in the regulatory structure that allowed some systemically important firms and markets to escape comprehensive supervision, failures of supervisors to effectively use their existing powers, and insufficient attention to threats to the stability of the system as a whole.”

The obvious question for critics of Bernanke is why the Fed itself did not do more to slow down the increases in the supply of credit from banks and the so called shadow banks? Perhaps the Fed could not do more, given its lack of adherence to money and credit supply targets and its heavy reliance on interest rates as its principal instrument of policy.

Given what happened in the housing price boom, it seems clear that policy determined interest rates should have been much higher to slow down the growth in credit. But it may also be argued that interest rates themselves are insufficient to moderate a credit cycle. This is an essentially monetarist point not addressed by Bernanke. In other words, to say there is more to monetary policy than interest rates. The supply of money and bank credit is deserving of control according to the monetarist critique. The Bernanke remedy for protecting the system against the prospect of a future financial crisis is predictably familiar: better regulation and more equity on the books of banks and other lenders. It may be argued that there will always be enough capital, regulated or not, in normal times, and too little in any financial crisis regardless of generally well funded financial institutions. Prevention of a financial crisis may prove impossible and the attempt to do so may be costly in terms of too little, rather than too much, lending and leverage in normal conditions (when lenders are appropriately default risk-conscious and do not make bad loans on a scale that makes for a credit and asset price bubble that ends in tears). The cure for a crisis should always be on hand and the Bernanke recipe will hopefully not be forgotten in the good times.

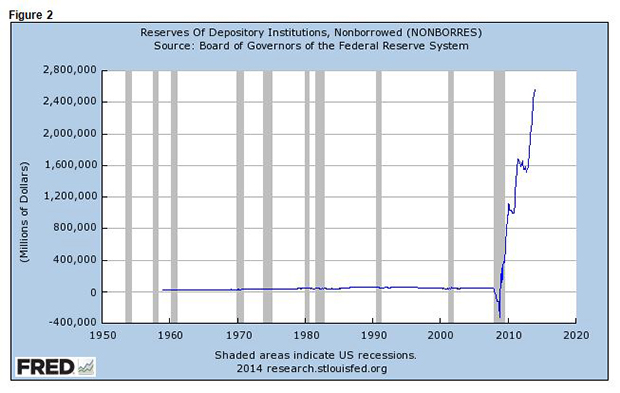

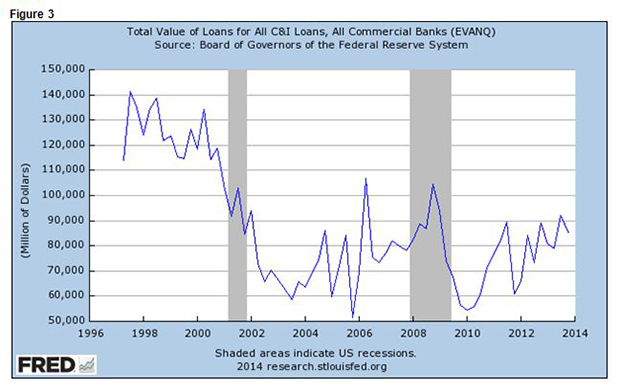

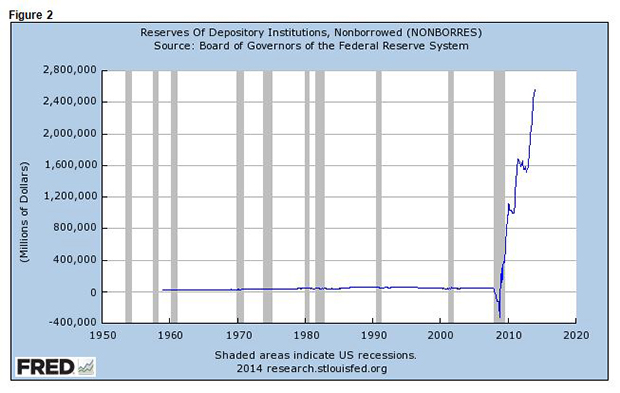

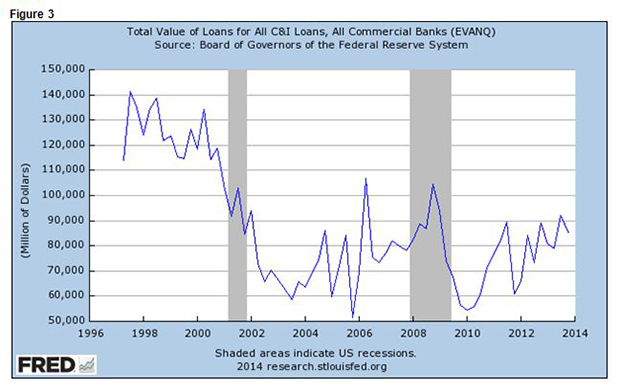

Any current concern about monetary aggregates would have to be on the liabilities side of the Fed balance sheet, conspicuous not so much for the volume of deposits held by the member commercial banks with the Fed, but with the historically unprecedented volume or ratio of deposits (cash) held by these banks with the Fed, in excess of their regulated cash reserve requirements. Also conspicuous is the lack of growth in bank lending to businesses – despite the abundance of cash on hand (see figures 2 and 3).

As Bernanke explained:

“To provide additional monetary policy accommodation despite the constraint imposed by the effective lower bound on interest rates, the Federal Reserve turned to two alternative tools: enhanced forward guidance regarding the likely path of the federal funds rate and large-scale purchases of longer-term securities for the Federal Reserve’s portfolio. Other major central banks have responded to developments since 2008 in roughly similar ways. For example, the Bank of England and the Bank of Japan have employed detailed forward guidance and conducted large-scale asset purchases, while the European Central Bank has moved to reduce the perceived risk of sovereign debt, provided banks with substantial liquidity, and offered qualitative guidance regarding the future path of interest rates.”

The use of forward guidance to help the market place forecast the path of interest rates more accurately, so reducing uncertainties in the market place leading hopefully to better financial decisions, predates the Bernanke chairmanship of the Fed. However, he should be credited with taking the Fed to new levels of transparency and much improved communication with both the marketplace and the politicians. In Bernanke’s words:

“The crisis and its aftermath, however, raised the need for communication and explanation by the Federal Reserve to a new level. We took extraordinary measures to meet extraordinary economic challenges, and we had to explain those measures to earn the public’s support and confidence. Talking only to the Congress and to market participants would not have been enough. The effort to inform the public engaged the whole institution, including both Board members and the staff. As Chairman, I did my part, by appearing on television programs, holding town halls, taking student questions at universities, and visiting a military base to talk to soldiers and their families. The Federal Reserve Banks also played key roles in providing public information in their Districts, through programs, publications, speeches, and other media.

The crisis has passed, but I think the Fed’s need to educate and explain will only grow.”

Historically US banks held minimum excess cash reserves, meeting any demand for cash by borrowing reserves in the Federal Funds market (the interbank market for cash), so making the Fed Funds rate the key money market rate and the instrument of Fed monetary policy. Holding idle cash is not usually profitable banking – but it has become so to an extraordinary degree. Furthermore, the large volume of excess reserves means that short term interest rates fall to zero from which they cannot fall any further. The reason they have remained above zero is that the Fed has been willing to reward the banks for their excess reserves by offering 0.25% p.a on their deposits with the Fed.

Every purchase of bonds or mortgage backed securities made by the Fed in its asset purchase programme must end up on the books of a bank as a deposit with the Fed. But before the extra phases of QE, the banks would make every effort to put their cash to work earning interest rather than holding them largely idle (as they are now doing). But it would appear that the Fed expects the demand for excess cash to remain a permanent feature of the financial landscape and can cope accordingly.

According to Bernanke:

“Large-scale asset purchases have increased the size of our balance sheet and created substantial excess reserves in the banking system. Under the operating procedures used prior to the crisis, the presence of large quantities of excess reserves likely would have impeded the FOMC’s ability to raise short-term nominal interest rates when appropriate. However, the Federal Reserve now has effective tools to normalize the stance of policy when conditions warrant, without reliance on asset sales. The interest rate on excess reserves can be raised, which will put upward pressure on short-term rates; in addition, the Federal Reserve will be able to employ other tools, such as fixed-rate overnight reverse repurchase agreements, term deposits, or term repurchase agreements, to drain bank reserves and tighten its control over money market rates if this proves necessary. As a result, at the appropriate time, the FOMC will be able to return to conducting monetary policy primarily through adjustments in the short-term policy rate. It is possible, however, that some specific aspects of the Federal Reserve’s operating framework will change; the Committee will be considering this question in the future, taking into account what it learned from its experience with an expanded balance sheet and new tools for managing interest rates.”

It seems clear that the market is not frightened by the prospect that abundant supplies of cash will in turn lead to more inflation as the cash is lent and spent, as monetary history foretells. The market clearly believes in the capacity of the Fed to remove the proverbial punchbowl before the party gets going. Judged by the difference between yields on vanilla Treasury bonds and their inflation protected alternatives, inflation of no more than 2% a year is expected in the US over the next 20 years. According to Bernanke, who is much more concerned with the dangers of deflation, arguing that inflation of less than 2% should be regarded as deflation (given the hard to measure improvements in the quality of goods and services). Therefore if inflation is less than 2% this becomes an argument for more, rather than less, accommodative monetary policy by the Fed.

The market clearly finds the Bernanke arguments and guidance highly convincing. These expectations are a measure of Bernanke’s success as a central banker. He has surely helped save the financial system from a potential disaster and has done so without adding to fears of inflation.

The US economy has not however enjoyed the strong recovery that usually follows a recession. Bernanke has some explanation for this tepid growth:

“In retrospect, at least, many of the factors that held back the recovery can be identified. Some of these factors were difficult or impossible to anticipate, such as the resurgence in financial volatility associated with the European sovereign debt and banking crisis and the economic effects of natural disasters in Japan and elsewhere. Other factors were more predictable; in particular, we appreciated early on, though perhaps to a lesser extent than we might have, that the boom and bust left severe imbalances that would take time to work off. As Carmen Reinhart and Ken Rogoff noted in their prescient research, economic activity following financial crises tends to be anemic, especially when the preceding economic expansion was accompanied by rapid growth in credit and real estate prices.16 Weak recoveries from financial crises reflect, in part, the process of deleveraging and balance sheet repair: Households pull back on spending to recoup lost wealth and reduce debt burdens, while financial institutions restrict credit to restore capital ratios and reduce the riskiness of their portfolios. In addition to these financial factors, the weakness of the recovery reflects the overbuilding of housing (and, to some extent, commercial real estate) prior to the crisis, together with tight mortgage credit; indeed, recent activity in these areas is especially tepid in comparison to the rapid gains in construction more typically seen in recoveries.”

He also blames the slow recovery on the unintended consequence of unplanned government fiscal austerity:

“To this list of reasons for the slow recovery–the effects of the financial crisis, problems in the housing and mortgage markets, weaker-than-expected productivity growth, and events in Europe and elsewhere–I would add one more significant factor– – 18 – Since that time, however, federal fiscal policy has turned quite restrictive; according to the Congressional Budget Office, tax increases and spending cuts likely lowered output growth in 2013 by as much as 1-1/2 percentage points. In addition, throughout much of the recovery, state and local government budgets have been highly contractionary, reflecting their adjustment to sharply declining tax revenues. To illustrate the extent of fiscal tightness, at the current point in the recovery from the 2001 recession, employment at all levels of government had increased by nearly 600,000 workers; in contrast, in the current recovery, government employment has declined by more than 700,000 jobs, a net difference of more than 1.3 million jobs. There have been corresponding cuts in government investment, in infrastructure for example, as well as increases in taxes and reductions in transfers.

“Although long-term fiscal sustainability is a critical objective, excessively tight near-term fiscal policies have likely been counterproductive. Most importantly, with fiscal and monetary policy working in opposite directions, the recovery is weaker than it otherwise would be. But the current policy mix is particularly problematic when interest rates are very low, as is the case today. Monetary policy has less room to maneuver when interest rates are close to zero, while expansionary fiscal policy is likely both more effective and less costly in terms of increased debt burden when interest rates are pinned at low levels. A more balanced policy mix might also avoid some of the costs of very low interest rates, such as potential risks to financial stability, without sacrificing jobs and growth.”

Bernanke then went on to paint an optimistic picture of the US economy:

“I have discussed the factors that have held back the recovery, not only to better understand the recent past but also to think about the economy’s prospects. The encouraging news is that the headwinds I have mentioned may now be abating. Near-term fiscal policy at the federal level remains restrictive, but the degree of restraint on economic growth seems likely to lessen somewhat in 2014 and even more so in 2015; meanwhile, the budgetary situations of state and local governments have improved, reducing the need for further sharp cuts. The aftereffects of the housing bust also appear to have waned. For example, notwithstanding the effects of somewhat higher mortgage rates, house prices have rebounded, with one consequence being that the number of homeowners with “underwater” mortgages has dropped significantly, as have foreclosures and mortgage delinquencies. Household balance sheets have strengthened considerably, with wealth and income rising and the household debt-service burden at its lowest level in decades. Partly as a result of households’ improved finances, lending standards to households are showing signs of easing, though potential mortgage borrowers still face impediments. Businesses, especially larger ones, are also in good financial shape. The combination of financial healing, greater balance in the housing market, less fiscal restraint, and, of course, continued monetary policy accommodation bodes well for U.S. economic growth in coming quarters. But, of course, if the experience of the past few years teaches us anything, it is that we should be cautious in our forecasts.”

It can be argued by his critics that the Bernanke innovations have been part of the problem rather than the solution. It would be very hard to argue that injecting liquidity and capital into the financial system to avert an incipient financial crisis in 2008-09 was the wrong thing to do. But it may yet be asked, then, if QE2 and QE3 were also necessary? Would not a sooner return to monetary normality have been confidence boosting, rather than undermining, business confidence, which is essential to any sustained recovery? Further bouts of QE have led to large additions to the excess cash held by banks, rather than additional lending undertaken by them that would have helped the economy along. Would the banks and the US corporations have put more of their strong balance sheets to work to help the economy along had monetary policy been less innovative, or at least had QE not been advanced as strongly as it was? Growth in bank credit and money supply (M2) has slowed down rather than picked up in recent years, despite the creation of so much more base money (see the figure on bank lending). That the banks have been able to earn 0.25% on their vast cash balances has surely encouraged them to hold rather than lend out their cash.

Furthermore, while fiscal policy could have been less restrictive in the short run, would any political failure to implement a modest degree of austerity at Federal and State level, not have made households even more anxious about their economic futures and the tax burdens accompanying them, leading to still less private spending?

The performance of the US economy over the next few years will be the test of the Bernanke years. If the US economy regains momentum without inflation, the Bernanke innovations will have proved their worth. They would then provide the concrete evidence that it is possible to create money, à outrance, and then take away the juice when that becomes necessary. Tapering of QE, the initial thought of which that so disturbed the markets in May 2013, is but a first tentative step to the actual withdrawal of cash from the system and the shrinking of the Fed balance sheet. The monetary experiment, conducted with deep knowledge of monetary history and theory that fortunately characterised the Bernanke years, remains an experiment. We must hope for the sake of continued economic progress both in the US and elsewhere that it proves a highly successful experiment.

1The Federal Reserve: Looking Back, Looking Forward, Remarks by Ben S. Bernanke, Chairman Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System at

Annual Meeting of the American Economic Association

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

3 January 2014

Source: Federal Reserve System of the United States, Speeches of Governors. All quotations referred to are taken from the published version of this speech.