Brian Kantor

12th January 2023

Introduction – Covid losers and winners

In the early days of the economy wide lockdowns of 2020, I remarked that “Today is a time of epidemiologists, central bankers and yes, of schemers too…..” I added that we will discover in due course whose reputations will have survived the economic crisis better intact. I was alluding to Edmund Burke’s unenthusiastic Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790)

The pandemic, as we well know, has had many losers and more than a few beneficiaries. Perhaps economists who have long observed monetary events are among the less disadvantaged by Covid19. Inflation reared up dramatically and new evidence about its causes and consequences was on offer and demanded interpretation. The experience and analysis of the high inflation nineteen seventies when I learnt my monetary economics became relevant again. The problem for the US economy and those with much diminished wealth is that the Fed does not have a monetarist model of inflation [1] As inflation came down after 1980 and money supply growth rates became less variable, and the supply of and demand for money were mostly well matched, such neglect of the role of money in determining inflation was perhaps understandable. The neglect turned out to be anything but benign under the extreme behaviour of the money supply after 2020. History may well come to judge central bankers much less kindly than the commentators appear to be doing today.

The updated evidence on inflation to December 2022

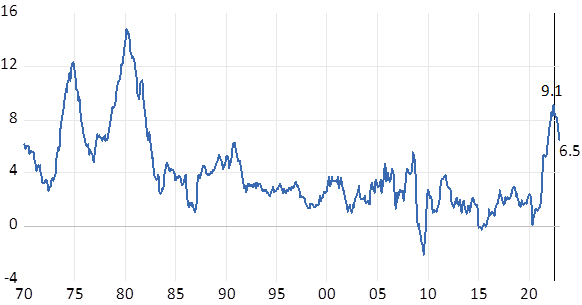

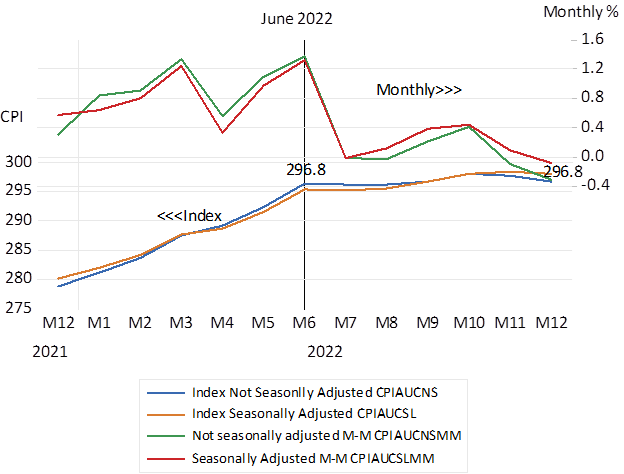

The headline inflation rate in the US peaked at 9.1% in June 2022. It fell rapidly and was 6.5% in December 2022. The monthly increases in the price level, slowed down very significantly after June. The CPI, not seasonally adjusted, was no higher in December 2022 than they were in June. The seasonally adjusted version was only slightly higher over the six months and both versions of the CPI fell in December 2022. On a six-month view there was no inflation in the US. (see figures 1 and 2 below)

Fig. 1; US Headline Inflation 1970-2012

Fig.2; The US CPI Unadjusted and Seasonally Adjusted and Monthly percentage change in US Prices January 2021 to December 2022

Source; Federal Reserve Bank of St.Louis and Investec Wealth and Investment.

The convention of measuring inflation as the year-on-year growth in the CPI has not helped to understand inflation dynamics under current highly unusual and volatile circumstances. Six months can be a very long time for an economy. Waiting a year to see what happens may be too long for a business or a central bank making a judgment and adjusting accordingly. If these monthly increases in the CPI remain at these levels for a further six months, the headline inflation will recede (but gradually) to close to zero by June 2023. There would be no good reason to expect a reversal of these trends, absent any new supply side shocks to the economy. Shocks over which the Fed has no influence, should be ignored because they are temporary and reverse as the recent post -Covid supply side shocks have reversed.

The demand side of the US price equation will not pose an inflationary danger if recent subdued trends in spending and in the money supply and bank credit are maintained. Without any sharp reversal of short-term interest rates this seems highly likely. The Fed has done what it needed to do to contain inflation and that was to contain increases in aggregate spending.

Unfortunately, the Fed greatly underestimated inflation and its persistence on the way up and has almost as egregiously overestimated it on the way down. Monetarists will argue – with new evidence on their side- that these failures to forecast the direction of inflation – that the Fed paid too little attention to the sharp swings in the growth in the money supply post 2020. These money swings were of unprecedented magnitude, which was every reason to attempt to moderate them and to have anticipated their impact on demand and prices.

There would seem no reason to risk nor threaten a recession to maintain low rates of inflation in 2023. Nor to frighten investors and businesses about such possibilities, given the outlook for inflation. The fright has been severe enough to remove trillions of dollars off the value of US equities and government and other bonds. There is good reason for the Fed and the market to forecast satisfactorily low rates of inflation in 2023. On the evidence of inflation and its causes, the Fed guidance should be on the likely and reassuring prospect of a soft landing.

A unique experiment in fiscal and monetary policy – Government spending and money creation – a predictably inflationary combination

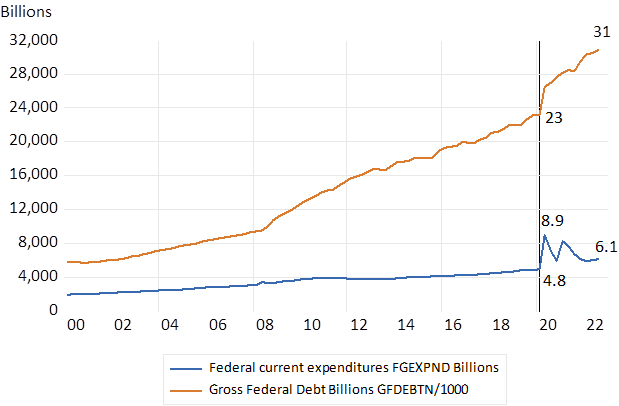

The US reactions to the lockdowns in the form of vast injections of income transfers and increases in the money supply provided a unique experiment in economic policy. In Q2 2020 current federal government expenditure grew by 4.1 trillion dollars, from 4.8tr to 8.9tr. The spending was funded mostly with debt a part was funded by running down the treasury balance with the Fed. Federal government debt increased by about 3 trillion dollars in Q2 2020. It grew further from 23 trillion pre-Covid to 32 trillion by Q3 2022.

The income sacrificed by the lock-down was immediately replaced and even exceeded by the generosity of government grants. As was reflected in an equally rapid increase in the deposits held by households at banks. Households initially saved much of the extra money transferred to them from the Treasury as Covid relief. The opportunity to spend more on services, face-to-face was restricted, as was the supply of goods by the anti-Covid repressions.

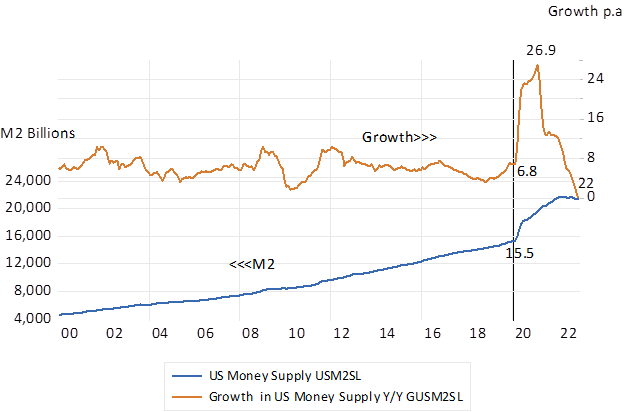

The broad money supply (M2) that includes most bank deposits and money market funds, increased from 15.5 trillion dollars in early 2020 to a peak of 21.7 trillion by February 2022, from which levels it declined in 2022. The growth in the money supply was as much as 27% p.a. in February 2021. This extra spending by the Federal Government, rapidly executed, was unprecedented even when compared to war times. The extraordinary growth in the money supply engineered by the Fed was also on a scale not previously known, even when compared to the actions taken during the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2008-09 to share up the financial system with money.

Fig.3 US Federal Government Expenditures and Federal Debt. Quarterly Data

Source; Federal Reserve Bank of St.Louis and Investec Wealth and Investment.

Fig. 4: The US Money Supply (M2) and Annual growth rates (Monthly data)

Source; Federal Reserve Bank of St.Louis and Investec Wealth and Investment.

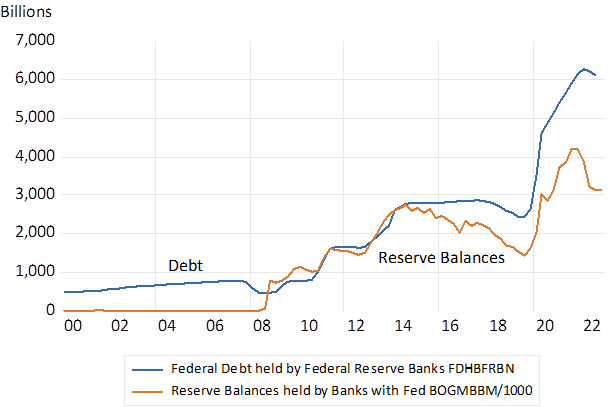

Quantitative easing (QE) that is the large-scale purchases by central banks of US government bonds was reversed and became quantitative tightening in late 2022, as may be seen in figure 5 below. To be noted also is the decline in the cash reserves of the US banking system- held with the Federal Reserve Banks in 2022. Nevertheless, the US banks continue to hold vast excess reserves, over the now redundant required reserves. They receive interest on these deposits with the Fed and judged by the absence of money supply and credit growth the banks have not been switching from cash to overdrafts and their like, as they might have done, had demands for credit been more buoyant.

Fig. 5; The Federal Reserve Banks. Federal Debt and Reserves of the Banking System

Source; Federal Reserve Bank of St.Louis and Investec Wealth and Investment.

Inflation surprises and their deflationary after-shocks.

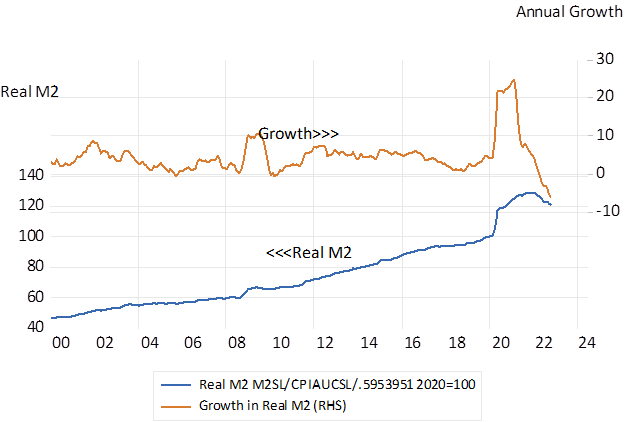

Yet the rapid and persistent increase in spending and in prices that followed the lockdowns in 2021 came as a surprise to many, including the Fed. But less so to those few economists who regard changes in the money supply as a reliable leading indicator of economic activity and of the price level. Attention to the forces that influence the supply of and the demand for money now leads one to conclude that the inflationary danger to the US economy, the prospect of a process of continuously rising prices, sustained over an extended period-of-time, has passed. The problem for investors and the market in stocks and bonds, is that the Fed has not yet shared this view. It should be noticed in figure 6 that the Money Supply adjusted for consumer prices has declined since January 2022 having peaked in September 2021. The year-on-year growth in Real M2 was a negative ( -6%) in October 2022

Fig.6; Real Money Supply (M2/CPI) 2020=100

Source; Federal Reserve Bank of St.Louis and Investec Wealth and Investment.

The increase in the inflation rate revealed in 2021, surprising the Fed and most market participants and their economic forecasters and advisors, caused the Fed and other central banks to react vigorously with much higher short term interest rates, intended to fight the new inflation. And to restore the reputation of the Fed as an effective inflation fighter.

These higher borrowing costs, combined with higher prices, perhaps a more powerful influence on intentions to spend, has absorbed the spending power of households. Higher prices have also increased the demand for money and helped reduce the post-Covid excess supplies of money (deposits at banks) held by households. Higher price levels, higher incomes and greater wealth all serve to increase the demand to hold money in portfolios, or as transactions balances. Higher prices have their supply and demand causes. They also have their effects – they restrain the willingness and ability to continue to spend more- all other influences, including especially ongoing money supply growth, remaining unchanged. Which to repeat has largely been the case even if not intentioned by the Fed.

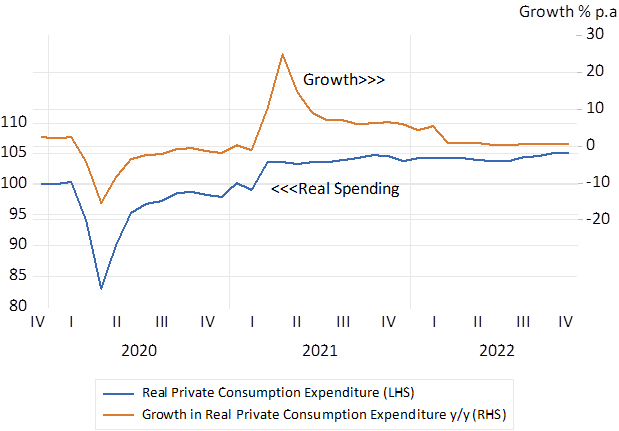

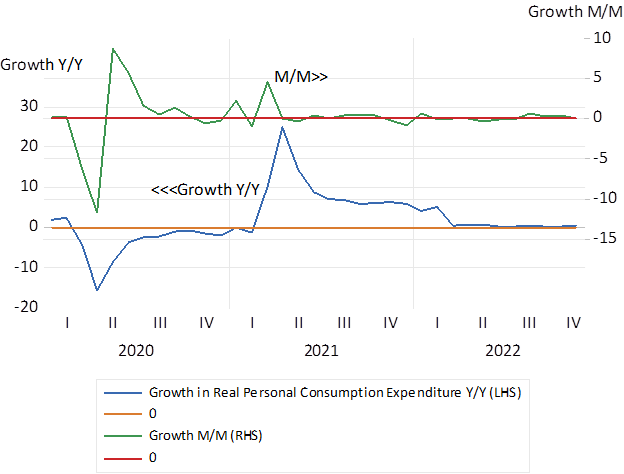

The flat path of private consumption expenditure in 2022

The absence of further growth in the money supply and bank credit in 2022 has helped to restrain the growth in real private consumption expenditure (PCE) as we show below. PCE accounts for about 70 per cent of all US spending and the capital expenditure, spending on plant and equipment, undertaken by US facing businesses is also dependent on the expected pace of real PCE.

Fig. 7; US Real Private Consumption Expenditure and Growth. Monthly Data to December 2022.

Source; Federal Reserve Bank of St.Louis and Investec Wealth and Investment.

Fig.8; Growth in PCE. Annual and Monthly

Source; Federal Reserve Bank of St.Louis and Investec Wealth and Investment.

Other measures of economic activity, for example the monthly surveys of activity in the manufacturing sector and now also for the service sector, indicate that the US economy is shrinking. Both the ISM and S&P Global services PMI readings are now below 50 for the US indicting a contraction in the supply of services that and have followed the contraction in US manufacturing PMI, a figure also below 50. The quarterly estimates of real GDP that draw upon higher frequency data are very likely to confirm that income and output growth is at best growing very slowly or is also in decline. If the future is to be like the past, these leading indicators of economic activity, contracting, portend a decline in real GDP, that is a recession.

The decline in the money supply and in the supply of and demand for bank credit (the asset side of bank balance sheets) was not an explicit intention of Fed policy – it has been an unintended consequence of higher prices and interest rates that have depressed the growth in spending by households and firms. The Fed does not target the growth in the money supply. Nor to my observation has the Fed ever referred to this slow growth in money as a cause or indicator of inflation to come.

Only persistent and continuous increases in aggregate demand- accompanied necessarily by increases in the supply of money – can perpetuate high rates of inflation

The Fed therefore may be said to have done its job containing permanently higher inflation. Inflation, defined as a continuous increase in prices, caused by an increase in the supply of money, in excess of the demand to willingly hold that money. That is a decision to hold money willingly in portfolios rather than convert the additional money supplied to the economy into additional demands for goods, services and assets, financial and real. An exchange of excess money for goods, services and assets of all kinds that are substitutes for cash in portfolios, causes their prices to rise. This transmission of extra money to extra aggregate demand surely explains a significant part of the higher prices realised for goods services and assets, financial and real of all kinds in the recovery from the lockdowns of early 2020. That is excess supplies of money led and inflation followed, as traditional monetary theory, would have predicted.

By mid-2022 enough of the extra excess money supplied earlier in response to the stimulus of 2020-21 had been added to US portfolios. With the aid of higher prices, the demand to hold money has caught up with the extra supplies of money The absence of excess real demands for goods and services, as revealed by the stagnation of real private consumption expenditures, indicates that the adjustment to higher inflation in the form of extra demands to hold money, has been made in the US.

It is only a further increase in the money supply that can keep aggregate demand growing fast enough to counter higher prices and to result in continuously rising prices. This danger has passed. Aggregate demand for goods and services in the US is now weak enough and will remain weak enough to call for a reversal of Fed actions taken to date- without causing permanently higher inflation. This inflation too will pass- absent accommodation of higher prices with faster money supply growth – which it is not receiving.

The Fed panicked and should have guided to a soft landing of less inflation to come without having to induce a recession.

The Fed has badly overreacted to its failure to contain inflation in the aftermath of Covid, as have other central bankers, including the Bank of England and the ECB. They have focused on inflation that has passed rather than the path of inflation to come. The Fed has failed to provide comfort that inflation is on the way down, as it is doing – given the absence of any strength in aggregate spending – that would be necessary to sustain continuous increases in prices.

Central bankers should not have been surprised as much as they were by post Covid stimulus and its impact on spending and on prices. Strains to complicated supply side chains and upward pressure on prices, given lockdowns were surely inevitable. Thereafter, the additional supply side shocks associated with the lockdowns and later with the Russian war on Ukraine became a further complicating factor driving prices still higher in 2022.

Yet the supply side shocks, most important, the impact of higher energy, also food and commodity prices, had clearly come to reverse by mid-2022. Accordingly headline inflation, the change in the CPI over twelve months, was bound to reverse sharply, as it has done, after the much higher prices of mid 2021 come to fall out of the Price Indexes.

Responding to supply side shocks to the price level.

Dealing appropriately with supply side shocks on the price level is a large part of the art of central banking. Central banks can only hope to influence the demand side of the price equation that equilibrates,with market clearing prices and quantities of all the many individual prices goods and services that make up the Consumer Price Index. The task set central banks is to help keep aggregate demand within the strict limits of the capacity of an economy to supply goods and services. This helps realise general price stability and full employment or potential output of the economy. It takes accurate forecasts of aggregate demand and supply to help fine-tune the economy with appropriately higher or lower interest rates, determined by the central bank. These interest rates act on the economy with a lag making forecasting the path of the economy essential to the purpose. It was a task admittedly made much more complicated in 2020 by the lockdowns of normal economic activity that were then overtaken by a major conflict in Europe.

Supply side shocks that will temporarily move the price level higher or indeed lower are therefore best ignored by policy setters and should be allowed to work their way gradually through the economy. Higher prices, as indicated earlier, are part of the normal adjustment process to less supplied or more demanded. Fewer than expected goods and services supplied to an economy could be the result of droughts or floods or famine or war. Or more usually, for less developed economies, a supply side price shock will be the result of a collapse in the foreign exchange value of a currency.

The case for ignoring supply- side shocks should be part of the forward-looking guidance central bankers offer the marketplace. It should therefore be carefully explained why the demand side of the economy may best be left as it was, not subject to higher or lower interest rates, given the absence of any demand side pressures on prices, should this be the case, as it has been the case in the US in 2022. And the central bankers should advise accordingly.

Steady as it goes is called for. A recognition of the limited powers of central bankers to always control prices within a narrow range- given the possibility of a severe supply side shocks -should be well understood and well communicated to the economy. The uncertain dynamics of inflation in 2021-2022 needed more sympathetic understanding and treatment than they appeared to receive from either the Fed or indeed most market commentators.

Post-Covid, central bankers including the Fed have continued to raise interest rates rapidly in response to higher prices, regardless of their supply side or demand side or mixture of both. They have not accommodated higher prices but allowed them to restrain demand and contain inflation – perhaps more than they needed to do. But they have not presented a confident front that inflation would and could be controlled without unnecessary damage to the economy.

It was surely possible to bring inflation back in line without a very costly recession as may still be the case. But with the right messaging it might also have been possible to do so without disrupting financial and asset markets that understandably became so fearful that the Fed would induce a recession.

Fanciful fears of self-perpetuating inflation explain the reactions of the Fed

Central bankers, rather than ignore the supply side shocks that partially explained the dramatic increase in the price level, fretted openly that economic actors would simply extrapolate their recent inflation experiences and can add continuously to prices. That higher inflation could lead to more inflation and so inflation becomes entrenched in the economy with highly damaging effects on economic growth over the long run. Much market commentary as well as Fed commentary has been about inflation becoming entrenched because of the danger of a higher wage- higher price spiral- that needed to be vigorously countered.

But such fears were highly exaggerated and have little evidence to support the notion of inflation simply feeding on itself. Absent a decision to react to a slow-down in an economy subject to the negative influence of higher prices, with still more of the money that initially caused prices to rise in the first place. It takes still more money to overcome the negative effect of higher prices themselves on demand and on the pace of economic growth. Prices will continue to rise only if the supply of money is allowed to continue to increase to offset the impact on spending of higher prices. This has not been the case in the US. The supply of money stopped increasing in 2022 and spending fell away to take the pressure off prices.

The determinants of inflation expected

It is surely not rational to set prices or wages regardless of what the market can be expected to bear. Economic actors with pricing power, including the power to demand higher wages, can easily be disappointed in their plans to charge more should demand for their goods and services at higher prices proves lacking. Slack being the difference between actual and potential GDP. [2] Economic slack can overcome more inflation expected as previously conventional central bank theories asserted. The highly reduced inflation equation in the Fed and other central bank models (Inflation = inflation expected – slack) indicates as such. The more slack, the less inflation, for any given expected inflation, is the theory.

Price setters would always like to raise prices or wages, to charge more, but they are restrained by the market for their offerings. They are forced to adjust their prices to what the market will bear, rather than what they might have expected their customers to have borne. The decline in inflation in the US recently helps make this important point. The US market in general is no longer able or willing to bear still higher prices for want of slack or potential slack.

The momentum of past inflation may well influence expected inflation. But it would not be rational to do so in some simple-minded way, given the possibility of slack in the economy. Any rational model of expected inflation would moderate inflation expected by slack expected. And the slack expected would depend upon the expected reactions of the central bank and might allow a role for the growth in money supply and bank credit.

We should expect more of a central bank than having to induce a recession to control inflation. The realistic promise should be one of a soft-landing and a central bank should acquire a reputation to deliver that. Inflation is to be avoided and can be avoided – but it should not have to take a highly destructive recession to do so.

Adding further increases in interest rates in the US and elsewhere to depress demand further in 2023 is a step too far- given the clear absence of buoyant demands from households. The opportunity exists for a soft-landing for the US economy, with inflation heading permanently lower to the 2% p.a. target of the Fed while avoiding a recession. But it will take an early pivot by the Fed to lower not higher interest rates by late 2023.

Employment, wages and prices- what is the relationship?

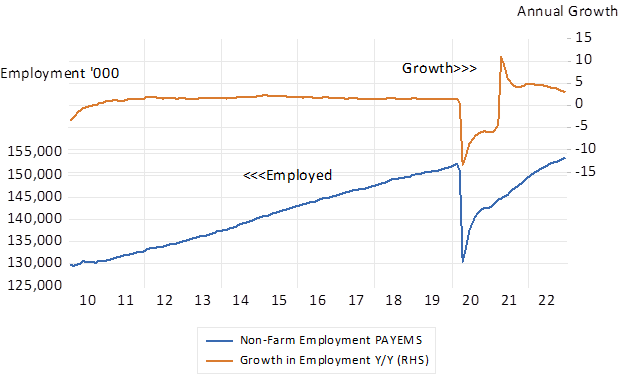

One other regular source of market moving news has been about the buoyant state of the labour market. The prospect of a recession, given very full employment, is a most unusual combination of circumstances. An un-employment rate below 4% and the growth in the numbers employed above 200,000 per month, as has been the case, are not normally consistent with a recession any time soon. (see figure 9 below)

As the financial markets were well-aware, a fully engaged labour force might well encourage the Fed to continue to worry more about the upside risks to inflation than the downside risks to growth. Especially if it held some conventional assumption about the higher wages that come with full employment will lead to further upward pressure on price- a wage-price spiral.

However interpreting the true state of the labour market- in particular the willingness of potential workers to supply labour – post Covid – is proving especially difficult. A taste for leisure rather than work has been facilitated by Covid relief and led to fewer potential employees seeking work. Given the lower participation rates in the labour force, employers particularly in the service sector, became unusually willing to pay-up to secure workers expected to remain in short supply.

The numbers employed outside agriculture appear to have caught up with pre-Covid levels. But are still below where pre-Covid trends in employment might have taken the labour market. The growth in the numbers employed month to month, which averaged a very steady 1.64% p.a. between 2011 and 2019. The post lockdown recovery saw the growth in US employment to peak at 10% in early 2021. The growth in the numbers employed now appears to be slowing down, consistently with a normal slow-down in spending.

Fig. 9; US employment and annual growth in employment. Monthly data

Source; Federal Reserve Bank of St.Louis and Investec Wealth and Investment.

The Fed view on the relationship between wages and prices – a recent pivot – and back

Yet the Fed in August 2020 revealed a willingness to experiment with the relationship between inflation and the state of the US economy, and more particularly, to experiment with the relationship between the state of the US labour market and wages and prices. Chairman Jerome Powell opined [3] that there was no predictable relationship between them and so the Fed would tolerate, even encourage, lower rates of unemployment and higher levels of employment, without exposing the economy to more inflation. In short, Powell pronounced that the Phillips curve that posits a costly trade-off of extra employment for lower inflation does not exist or, in his words, the curve has flattened.

Economic theory has long explained the demise of the Phillips curve observed first in the high inflation slow growth, stagflation 1970s. Economic agents, be they firms or trade unions, or indeed highly paid executives, learn to build inflation into their price and wage settings. A view on inflation – inflationary expectations – are rationally baked into their budgets and plans, and current price and wage decisions. Thus it is not realised inflation that will have a real impact on hiring and production decisions. Since expected inflation will be reflected in the prices and wages agreed to in advance, it will be inflation surprises, higher or lower, that will invalidate, to a degree, the best-laid plans of businesses and their employees and force an adjustment to price and wage plans.

The financial markets and the outlook for inflation – fighting the Fed and losing

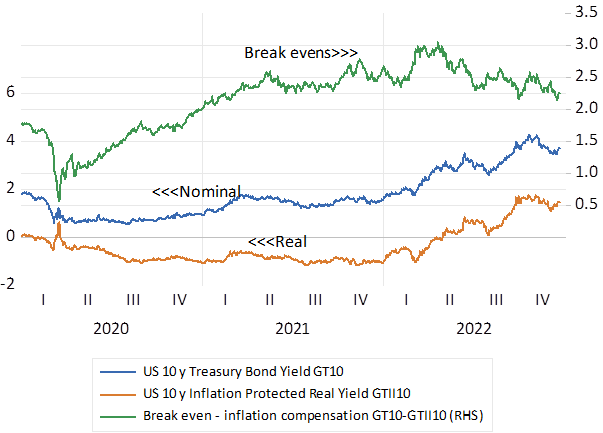

The marketplace, correctly in my opinion, has maintained a different more benign view of the outlook for inflation than has the Fed and its officers. Expectations of inflation over the long run are revealed by the differences between the yield on vanilla and inflation linked bonds. They have remained well contained and close to the 2% p.a. inflation target of the Fed.

By year end 2022 the difference between the nominal yield offered by a 10 year US Treasury and the real, fully inflation protected, yield on a 10 year US bond, a TIPS, (Treasury Inflation Protected Security) was of the order of 2.25% p.a. Investors exposed to the risk that inflation would erode the purchasing power of their fixed interest income, of 3.7% p.a. for ten years were offered an extra 2.25% p.a. to accept this inflation risk. Investors in either the vanilla or inflation protected bonds would breakeven if inflation turned out to average 2.25% p.a over the next ten years as expected in the bond market. This inflation compensation -the breakeven yield spread provides a highly objective view of inflation from investors with much to gain or lose should inflation turn out higher or lower than expected.

The surprising feature of the behaviour of the long bond yields through a period of much higher inflation is that real as well as nominal bond yields have risen sharply- helping to close the gap between them. Higher nominal yields to accompany more inflation and to provide compensation for more inflation expected is not a surprise. The surprise is the increase in real yields that have accompanied more inflation and amidst widespread expectations of slower growth – even recession to come. Forces that might ordinarily be expected to reduce the case for businesses to raise more capital and lead to lower rather than higher real interest rates.

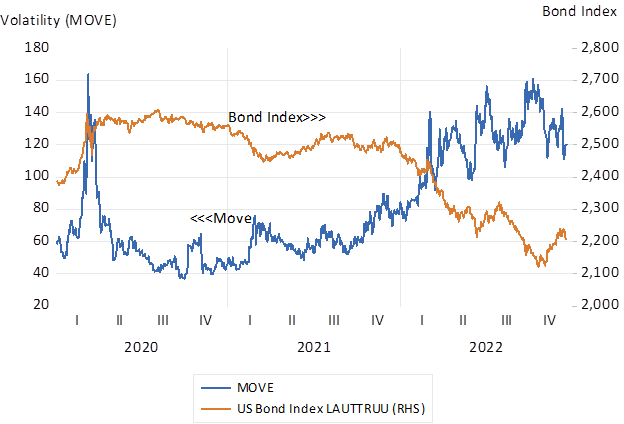

My explanation for this anomaly was that volatility as measured in the bond markets had also risen with uncertainty about the actions the Fed might take to control inflation. Therefore, all yields, nominal and real, rose to compensate investors for the extra risks they believed they were taking. More perceived risk means lower bond and equity values in 2022 that are necessary to provide higher expected returns in both the equity and bond markets in 2022. Subject to these increased risks to interest rates the bond markets in 2022 proved anything but safe havens for investors.

Fig.10; US Bond Market; 10 year Conventional and Inflation Protected Treasury Bonds. Yields and inflation compensation (break- evens)

Source; Bloomberg and Investec Wealth and Investment.

Fig. 11; US Bond market volatility index (Move) and the Bond Index. Daily Data

Source; Bloomberg and Investec Wealth and Investment.

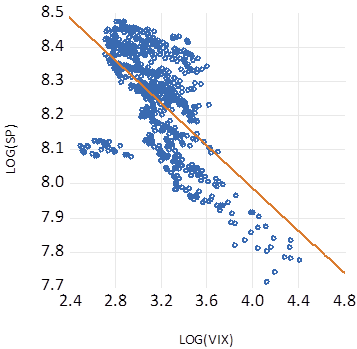

Fig. 12. The S&P 500 index and the Volatility Index (Vix) Log Values Daily Data 2020- 2022

Source; Bloomberg and Investec Wealth and Investment.

Conclusion – The Fed is now following rather than leading the data

Expected inflation or expected GDP influences current valuations and business operations. The future is all in the price as may be said, but the future may turn out very differently. It is only surprises that move financial markets and the real economy as in the expectations adjusted Philips curve discussed earlier. These ideas were incorporated into economic theory in the nineteen seventies and eighties and the developers of the theory were rewarded with a number of Nobel Prizes for economics. [4]The task of central banks following the expectations sensitive and now conventional central bank wisdom, is to help anchor inflationary expectations to avoid such surprises. The Fed hopes to do so by providing forward guidance on central bank policy intentions with which the market hopefully concurs and behaves accordingly providing a higher degree of market stability. Thus, by reducing uncertainty about the future path of inflation and the real economy helpful guidance helps make business plans more accurate and less subject to alterations in output and employment plans. Closing the potential gap between expectations and economic and financial market outcomes is thought to reduce risk and required returns and therefore helps promote economic growth.

However, the Fed in its recent latest post- rapid inflation incantation, has been very disinclined to offer any comfort to investors about its intentions. Fears of unknown, and what are presented as highly unpredictable inflation, rather than slow growth, remain uppermost in its thinking.

The notion that higher inflation could be self-fulfilling and harmfully so for the economy over the long run appears to dominate their approach. The Fed appears willing to accept a recession if necessary to the purpose of reducing inflation expected and so inflation. A view that the market is understandably fearful of. And to some extent the market has not accepted the Fed view as has been revealed in forward interest rates, lower forward rates, than appear in Fed Open Market Committee guidance (the so-called dot plots of OMC members)

My own view is that the market is very likely to be closer to the truth on inflation and therefore on the path of interest rates than the Fed. That the Fed, more than the market, is likely to be surprised by the inflation and interest rate outcomes.

Central bankers are unlikely to emerge from Covid with their reputations for sound judgment about inflation fully intact. No more than the epidemiologists whose predictions of disaster proved highly fallible. The case for economic lockdowns given their cost and collateral damage has become increasingly suspect with the knowledge since gained.

Perhaps the next time society is threatened by an epidemic the cost-benefit analysis of economists may carry more weight with the politicians and their officials who appear so independently powerful to exercise executive authority. And maybe next time, without the lockdowns, the temptation to add as much stimulus as was added post-Covid – with all its consequences – inflation followed perhaps by recession – will be resisted to a greater extent.

The Jury will stay out on these issues through much of 2023. My contention that inflation is heading lower because the money supply is decreasing is well supported by the latest trends as of December 2022. The monthly increases in the US CPI are all pointing to much lower headline inflation. A trend that will become ever more obvious to all observers including those at the Fed. The case for higher short term interest rates will then surely have been lost. The case for assisting the US economy with lower interest and a pick-up in money supply growth rates will then become irresistible.

[1] I offered a monetarist interpretation of these developments in early 2022

Brian Kantor, Recent Monetary History; A Monetarist Perspective, Journal of Applied Corporate Finance • Volume 34 Number 2 Spring 2022

[2] I wrote about the beliefs of central bankers in 2016

Brian Kantor, The Beliefs of Central Bankers About Inflation and the Business Cycle—and Some Reasons to Question the Faith. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance • Volume 28 Number 1 Winter 2016.

[3] All references to Chairman Powell and his thoughts are taken from his speech to the symposium on economic policy organized by the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City 8/27/2020;

New Economic Challenges and the Fed’s Monetary Policy Review

Chair Jerome H. Powell. At “Navigating the Decade Ahead: Implications for Monetary Policy,” an economic policy symposium sponsored by the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Jackson Hole, Wyoming (via webcast)

[4] My own attempt to follow the chain and train of such new thoughts can be found in Rational Expectations and Economic Thought, Brian Kantor, Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. XVII, December 1979,pp 1422-1441