Funding extra government spending via loans from the central bank, can be a helpful form of government finance when spending is growing rapidly to meet an emergency.

Today is a time of epidemiologists, central bankers and yes, of schemers too. We will discover in due course whose reputations will have survived the economic crisis better intact.1

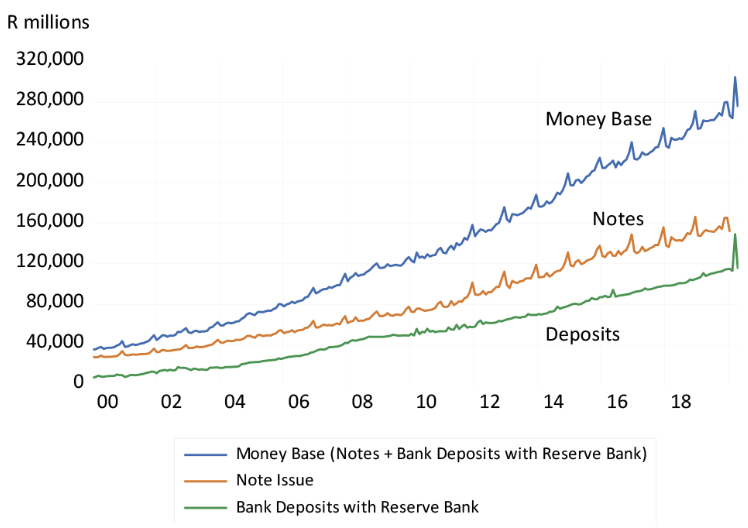

Central banks have an essential duty to create extra money for a growing economy. They do so on a consistent basis in normal times. Their extra money comes in two forms: as notes and coins and in the deposits private banks keep with their central banks.

The SA Reserve Bank has not failed in its duty to supply more cash to the economy over the past 20 years. For much of the period it might have supplied too much cash. More recently, it can be criticised for supplying too little for the health of the economy as we shall demonstrate.

The sum of the notes and the deposits issued by the SA Reserve Bank (the money base) grew by 7.9 times between 2000 and April 2020, from R35bn to R275bn at an average compound rate of 8.7% a year over 20 years.

Source: SA Reserve Bank and Investec Wealth & Investment

1 With apologies to Edmund Burke, responding to the excesses of the French Revolution: “Today is a time of sophists, economists and schemers.” – Reflections on the French Revolution

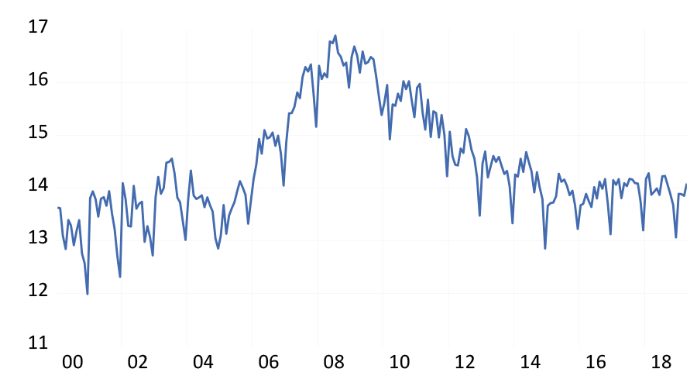

Figure 2: Calculating the money multiplier – the ratio of broad money (M3) to central bank money (money base) 2000 to 2019

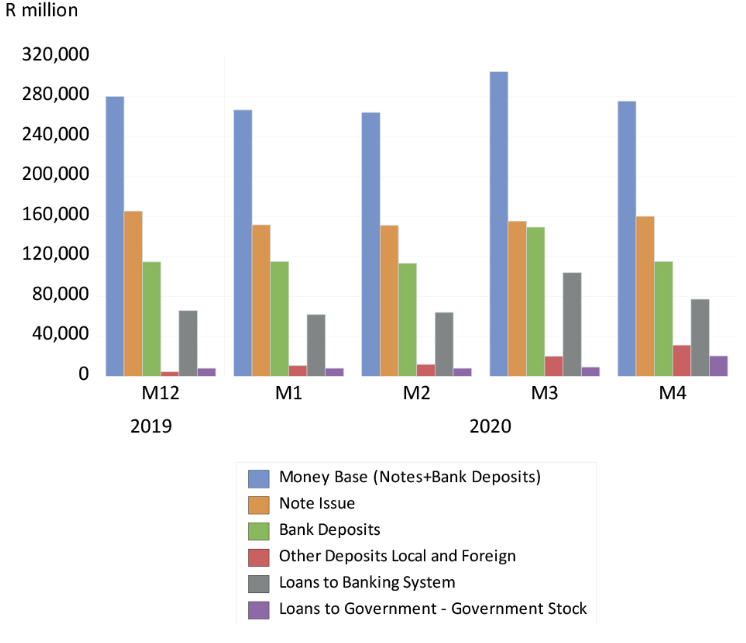

The Reserve Bank balance sheet has been updated to April 2020. The money base (notes plus bank deposits) as at the end of April 2020 was in fact R5bn smaller than it was at 2019 year-end, despite the crisis. The money base fell by R29.4bn between March and April 2020, even though the note issue itself rose by R4.82bn in April, surely in response to crisis fears. The deposits of the banks however fell more sharply, from R103.4bn in March to R77.34bn by April.

The Reserve Bank’s portfolio of government stock, a small part of its asset portfolio, grew from R8.1bn at year-end to R20.6bn in April. This may be compared to loans made by the Reserve Bank for the banking system. They grew from R65.8bn at year-end to R103.9bn by March, but then (surprisingly in the crisis circumstances) fell back to R77.34bn by April month-end.

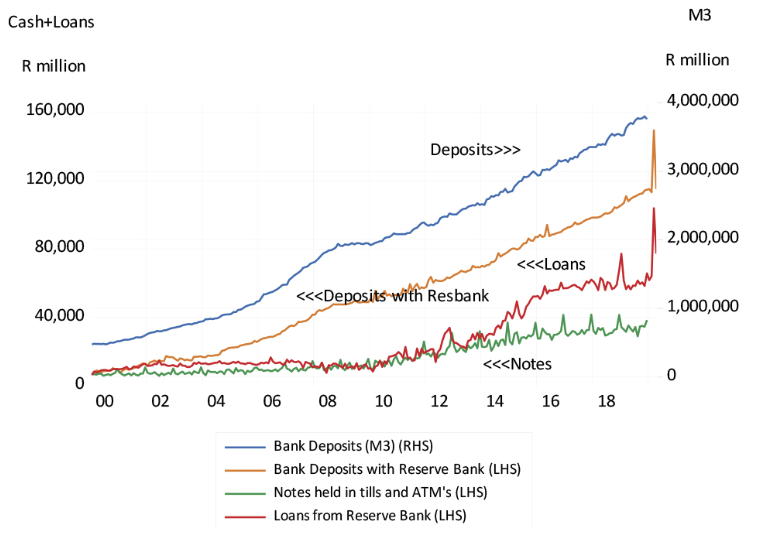

If the Reserve Bank were to embark on meaningful money supply growth loans to the banking system, its holdings of government stock would have to increase meaningfully. An increase in Reserve Bank lending to the banking system on favourable terms would allow the banks to support extra issues of short-term Teasury obligations at hopefully much lower rates of interest (see figures below for details of the balance sheets of SA banks since 2000 and of the Reserve Bank balance sheet this year).

Figure 3: SA banks deposit liabilities (M3), and uses and sources of cash

Source: SA Reserve Bank and Investec Wealth & Investment

Figure 4: The Reserve Bank balance sheet (selected items) to April 2020

Source: SA Reserve Bank and Investec Wealth & Investment

There is always a temptation for a government to borrow money from its central bank to fund its expenditure by issuing money. Almost zero cost money may be issued as an alternative to raising taxes or paying interest on the debt it raises to fund its expenditure. It is a temptation that is widely (but not always) resisted.

How much money should be created as a service to an economy and its banks that manage the payments system? The answer in very general terms is for a central bank to supply not too much and not too little cash for the economy. Not too much – that is not to supply more than the households, businesses and banks would willingly hold as a reserve of spending power. But to supply enough extra cash to satisfy demands that would grow normally in line with real economic activity.

It is not the supply of money and of associated bank and other credit that represents inflationary dangers or the danger of asset price bubbles that must all end badly for an economy. It is the excess of the supply of money – over the willingness to hold the extra money supplied – that is to be avoided if inflation is to be controlled.

Also to be avoided is to supply too little money. If the supply of extra money is constrained, economic actors would be inclined to cash in assets or save more to build up a cash reserve. This too would not be good for an economy.

The task central banks set themselves is to smooth the business, money and credit cycles by adjusting the cost of the money they supply to the economic system. They raise the repo or discount rates they charge the banks who borrow from them, when the economy and the supply of bank credit appears to be accelerating too rapidly. They will also lower the cost of their money, reduce the repo or discount rates, to encourage the banks to extend more credit to avoid or overcome a recession. However this fine balance of additional supplies of and demands for money is seldom achieved. The business cycle has not been eliminated by modern monetary policy.

The business cycle – extended periods of above and then below potential real growth – can be mostly linked to phases of more rapid and then much slower growth in money supply and bank credit. Inflation, for which a central bank usually has a target range, will tend to follow the direction of the business cycle.

The times when the price level takes a course independently of the direction of the business cycle calls for particularly sensitive attention by the monetary authorities. Raising interest rates in response to a supply side shock to the economy that results in temporarily higher prices (for example following a shock to the oil price, food supplies or to the exchange rate) may well prove to be pro- rather than counter-cyclical. It may slow the economy down further than it might otherwise have done.

These norms and objectives for monetary policy do not apply in the extremes of a crisis, when sudden demands for extra cash threaten the banking financial and payments system. The solution for a crisis is for a central bank to supply as much extra cash as is necessary to prevent ordinarily sound businesses and financial institutions from going under and dragging the economy down with them.

Shutting down an economy to fight a pandemic is a new challenge for monetary policy. It also calls for a rapid increase in the supply of central bank money and sharply lower interest rates where there is room to lower them.

Funding extra government spending via loans from the central bank, or funded by a banking system well supported with loans from the central bank, is a helpful form of government finance when spending is growing rapidly to meet an emergency, and correctly so. Funding with money or near money avoids the long-term burden for taxpayers of funding extra debt issues at high interest rates in an unwilling capital market. And by adding extra money to the system, it makes a much-needed recovery of spending more likely when the economy comes out of lockdown.

The extra money cannot be inflationary until the economy and spending recovers. At that point, the growth in the supply of money and credit can be reduced or reversed in the usual way.

When an economy is forced to its knees, an emphasis on inflation targets makes little sense. SA urgently needs and deserves (proportionately) as much extra money as is being provided in the developed world. By contrast, the money base in the US has been increased by 40% this year with more money on the way.