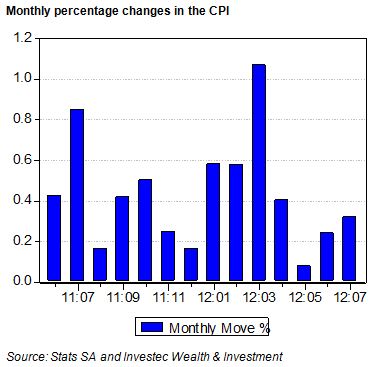

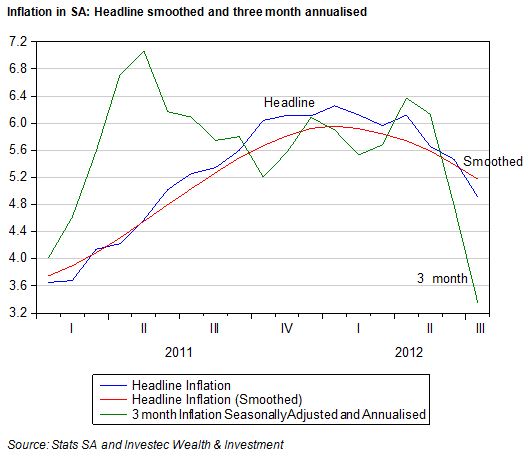

Headline CPI inflation declined to 4.9% for the 12 months to July. This welcome lower rate of inflation does not tell the full story of the direction of prices. A year can be a long time in economic life and what happens to prices in between can be much more revealing about inflation trends. Over the past three months prices have increased very slowly – more slowly than they did a year ago, as we show below. Prices rose by 0.08% in May, 0.24% in June and 0.32% in July.

These relatively small monthly increases compared to a year before have brought down the three month rate of inflation, seasonally adjusted and annualised, sharply lower to well below 4%. ( See below)

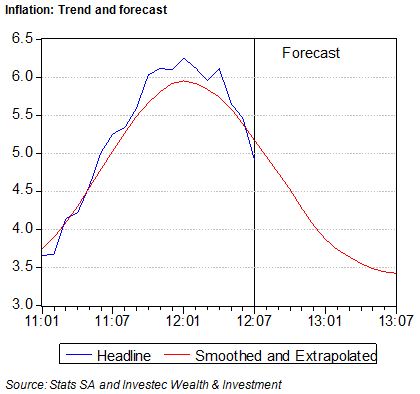

If current trends in the CPI persist, the outlook is for an inflation rate of no more than 3.5% this time next year, as we show in the chart below. It should be noticed that monthly increases in the CPI were particularly rapid early this year, thus offering the possibility of seeing year on year inflation come down further in early 2013 (that is, if monthly increases then turn out to be below the rather high monthly increases of early 2012).

These trends could be damaged by a combination of a weaker rand and supply side disruption (drought and war) which might drive global grain and oil prices higher. If global growth gathered enough momentum to drive up metal and commodity prices generally, for demand side reasons, the rand might well strengthen to moderate such influences on the prices of imported and exported goods. Faster growth in export markets would be very helpful to the SA economy. It could bring faster growth without more inflation, because the rand will strengthen.

Slower global growth would be very likely to weaken the rand and cause the inflation numbers and outlook to deteriorate. The domestic economy will also be harmed by such trends. It would mean slower growth and higher inflation. The case for raising interest rates under such adverse circumstances is a poor one. It would mean still slower growth without any predictable impact on the inflation rate.

The Reserve Bank, under present leadership, seems unlikely to raise rates should this adverse scenario materialise. If the economy stays its present course (less inflation and growth that remains below potential growth), the case for lowering rates improves. The more hopeful scenario – the SA economy to benefit from a reviving global economy and higher commodity prices and a more valuable rand meaning no more inflation – the case for lower interest rates also improves.

And so in the light of currently lower inflation, the case for lower interest rates has improved. Furthermore it is hard to contemplate more favourable or less favourable economic circumstances that would drive short rates higher. We might describe the outlook for (lower) interest rates in SA as the Marcus Put. Brian Kantor