Our markets have been dominated by global events – with the JSE, the rand and to a lesser extent the SA bond market gyrating closely in tune with global markets, especially emerging markets, in response to degrees of global risk aversion.

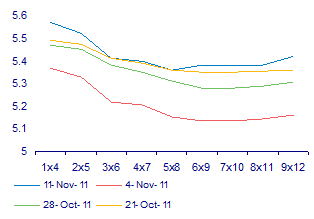

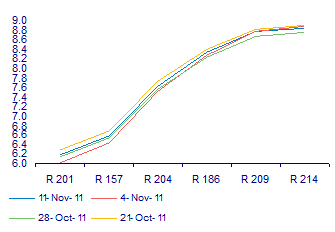

Friday 11 November however was an unusual day in the SA bond and equity markets. Market moves were dominated by an SA specific event: the meeting and outcome of the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) of the Reserve Bank that reported back on Thursday afternoon. The market by Friday had significantly revised its view on the interest rate outlook. The market had attached only a small probability of a cut in rates on the Thursday before, but had been pricing in an above 50% probability of a cut within three months.

As we show below the market, in the light of what was said rather than what was decided at the MPC meeting, now regards the chance of a cut in rates anytime soon as highly remote. The yield curve that was upward sloping, indicating the likelihood of higher interest rates a year out, has shifted up and become steeper indicating higher rates to come, and sooner.

Clearly such expected interest rate moves are not helpful to the growth outlook for SA, which has if anything deteriorated in recent months, with the risks attached to Europe and its implications for global growth, as was confirmed by the Reserve Bank. Also indicated by the Reserve Bank was the weakness in domestic demand.

Hence the failure on Friday of the equity market to respond to better news about Europe or to the strength in offshore equity markets. The rand was similarly unmoved by stronger equity markets, perhaps also because the SA growth outlook had deteriorated.

It is surely clear to all on the MPC that the SA economy can do with all the help it might get from lower interest rates. It is not getting that help because the inflation outlook has deteriorated. The inflation outlook however has deteriorated because of a weaker rand; the rand is weaker for reasons completely out of the influence of the MPC, namely the Eurozone debt crisis.

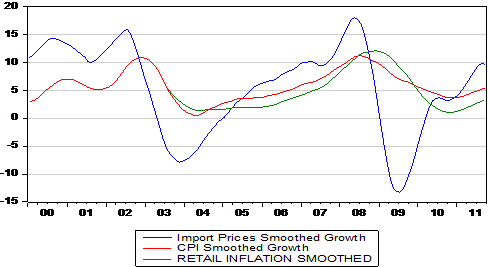

The MPC should know but seems not to recognise that interest rate settings in SA have no predictable influence at all on the exchange value of the rand. As we show below the correlation between changes in interest rates and the changes in the value of the rand is close to zero – there is no observable influence of changes in interests rates on the exchange value of the rand and therefore on the prices paid for imported and exported goods that in turn have such a strong direct bearing on price setting behaviour in SA. The correlation co-efficient is close to zero. Moreover, since the MPC last cut interest rates in November last year, the rand has been all over the place driving inflation in one and then the other direction.

The evidence is overwhelming that interest rates have not had any meaningful influence on inflation outcomes in SA. Moreover they cannot be expected to have any predictably anti-inflationary purpose until the rand responds to SA, rather than global forces. This surely cannot be predicted to happen any time soon.

Like it or not monetary policy can only influence aggregate demand in SA. Its impact on the price level has been and will be overwhelmed by moves in the rand. Thus higher interest rates, especially when accompanied by a weaker rand and the higher prices that follow, can only mean less spending and less output and employment – without perhaps having any helpful influence on inflation or the outlook for inflation. By not lowering rates or even, heaven forbid, contemplating raising them, the MPC has consistently burdened the SA economy with less growth without any predictable influence on inflation.

And should the response to this critique take the form that monetary policy must fight not just inflation but inflationary expectations, it should also be recognised that there is also no evidence of this in South Africa. Inflation may have affected inflation expected in SA (even though inflation expected has been remarkably stable, suggesting that such effects have been of small magnitude). But there is no evidence of any feedback effects (ie more inflation expected leading to more inflation). It has not happened perhaps because the theory is faulty but much more obviously, because inflation in SA follows the exchange rate and does not lead it.

South Africans have been called upon to make sacrifices in the form of slower growth for lower inflation or at least inflation in line with inflation targets, which make no sense at all. A new narrative for SA monetary policy is long overdue. This does not have to mean more inflation or more inflation expected. If the narrative recognises and explains the facts of the matter and monetary policy were set accordingly it would mean faster and more sustainable rates of growth. By attracting more capital to SA to fund growth could mean a stronger rather than weaker rand over the long run and so less rather than more inflation over the long run. But this would mean recognising that inflation targeting – given the openness of its financial and currency markets to unpredictable global forces – has not been a sound basis for monetary policy in SA. Brian Kantor