With the SA inflation rate above the upper band of the target it was inevitable that the Reserve Bank’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) at its latest meeting and Press Conference, would focus on inflation and the risks to it rather than the unpromising growth outlook and the prospect of even slower growth to come. The question that should have been asked of the Governor and the members of the MPC is why they appear to believe that higher short term interest rates would help to reduce inflation in SA. The connection is by no means as obvious as traditional monetary theory might suggest- that higher interest rates lead to less inflation and vice-versa.

The answer, following conventional theory, might have been that higher rates would slow down spending and so further inhibit pricing power at a retail and manufacturing level. It might well do that- slow down spending further and harm the economy accordingly. But by slowing down the economy it would discourage foreign investors from investing in South Africa. This could mean a weaker rand and so more rather than less inflation. Slower growth with more inflation is not something the Reserve Bank should wish to inflict on South Africans. The evidence is however very strong that interest rate changes in SA do not have any predictable impact on the exchange rate and therefore on inflation.

The reality is that the exchange value of the rand is highly unpredictable and volatile, highly independently of SA short term interest rates, for both global and SA reasons that encourage or discourage the demand for risky rand denominated assets. This means that inflation is beyond the immediate control of the Reserve Bank. Therefore while low inflation is a highly desirable objective for economic policy – inflation targeting –becomes a very bad idea when domestic demand is growing too slowly rather too rapidly for economic comfort. Higher interest rates in these circumstances are a bad idea because higher interest rates leads to still slower growth in the economy and because growth determines capital flows and so the exchange value of the rand, higher short rates imposed by the Reserve Bank may in fact lead to more rather than less inflation.

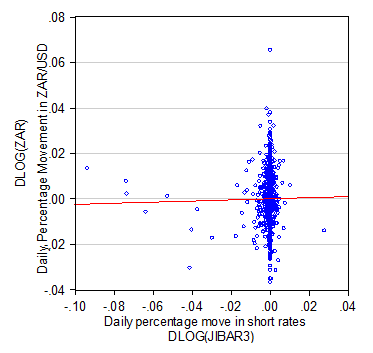

In the figure below this point is made. It is a scatter plot of daily percentage moves in the ZAR/USD exchange rate and short term interest rates, represented by the 3 month Johannesburg Inter bank rate (JIBAR). As may be seen there has been about the same chance of an interest rate move leading to a more or a less valuable rand since January 2008. The correlation statistic for this relationship is very close to zero, in fact 0.000006 to be exact.

A scatter plot- daily percentage moves in short rates and the ZAR ( daily data January 2009- September 2013)

Source I-net Bridge Investec Wealth and Investment

The theory behind inflation targeting is that exchange rates follow rather than lead domestic inflation. The theory does not hold for an economy that depends, for want of domestic savings, on a highly variable flow of foreign capital. This leads in turn to a highly variable and unpredictable exchange rate. The best monetary policy can do in the circumstances is to accept this reality. That is to allow the exchange rate to act as the shock absorber of variable capital flows and to accept the consequential short term price trends – while using interest rates as far as they can be used – to moderate the domestic spending and credit cycles.

In practice this is how the Reserve Bank has reacted to recent exchange rate weakness that was so clearly not of its monetary policy making. Doing nothing by way of interest rate changes or intervention in the forex markets was the right thing to do. It remains the right thing to do until the global capital markets calm down. It is just as well that in the past week the rand has strengthened, improving the inflation outlook and so helping to keep the Reserve Bank on the interest rate fence, where it should stay.

If the rand stabilizes – better still strengthens further in response to global forces or SA reasons – for example better labour relations – one may hope for lower interest rates. The weakness of domestic spending calls for lower not higher interest rates. Lower rates would will help stimulate faster growth. And so doing would add expected value to SA companies, especially to those heavily exposed to the SA economy and the domestic spender. This would add to the incentives for foreign investors to buy JSE listed shares. It would also encourage foreign controlled businesses in South Africa to add to their plant and equipment and retain cash rather than pay out dividends to foreign shareholders. Such a more favourable outlook for the SA economy and the capital that flows in response may well strengthen the rand and improve the inflation outlook.

A focus on inflation targets, beyond Reserve Bank control via interest rate determination, prevents the Bank from doing the right thing for what interest rates do influence in a consistent way and that is domestic spending. Lower interest rates and the demands for credit that accompany them can stimulate demand and higher interest rates can be used to discourage demand when it becomes excessive. When domestic spending growth is adding significantly to domestically driven pressures on prices higher interest rates are called for. This is clearly, and by the Reserve Bank’s admission, not the case now. The opposite is true, domestic demand is more than weak enough to deny local price setters much pricing power. And in these circumstances higher wages conceded to Union pressure lead to fewer jobs and on balance less rather than more spending. Prices are set by what the market will bear rather than operating costs. Operating margins rise and fall with operating costs- – in the absence of support form customers- and prices do not necessarily follow.

A target for what is judged to be sustainable growth in domestic spending might be a useful adjunct to monetary policy that regards low inflation as helpful to economic growth. A target for inflation, without a predictable exchange rate, just gets in the way of interest rate settings that should be helpful for growth.