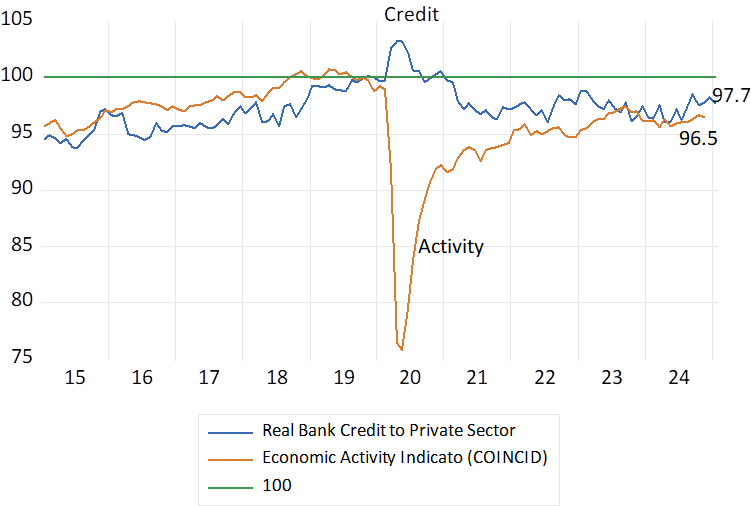

I propose a case study in monetary policy. The economy to be investigated is stagnant. Very little growth in GDP is being recorded. Spending on capital goods, plant and equipment is even more subdued than spending by households. The demand for bank credit has not grown in real terms for a number of years. Indeed, is still below pre Covid levels, as is economic activity. But not all the news is bad. Inflation is well down – indeed prices have hardly increased for six months.

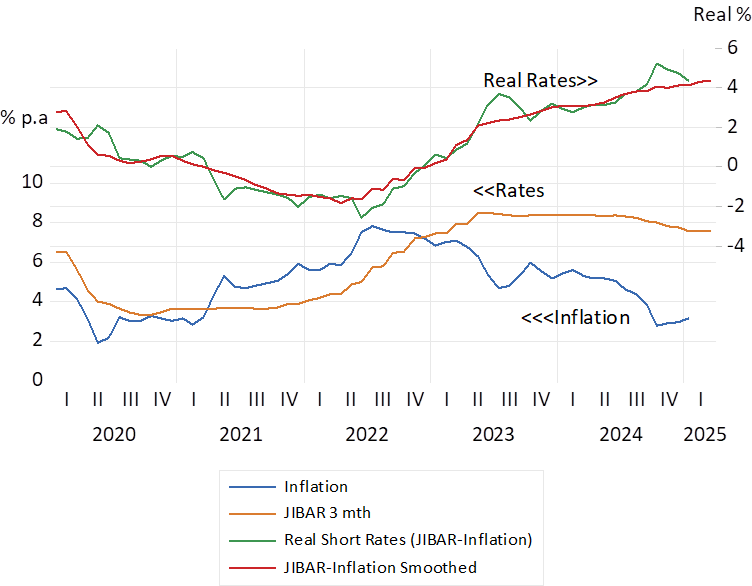

But short-term borrowing costs have lagged well behind the declining inflation rate. The difference between the interbank lending rate for 3 months and annual inflation, real rates, is 4.4% p.a. a level not approached since 2003. It would seem perfectly obvious that the appropriate policy response would be to cut the key repo rates immediately and significantly to stimulate much needed spending growth for which interest rate settings are a significant discouragement.

But as readers will have guessed the economy is South Africa. The charts tell the story. Yet the Reserve Bank has successfully guided the money market to expect little by way of interest rate relief. The Forward Rate Agreements between banks indicate that short rates are expected to decline by no more than 50 b.p. over the next twelve months and that even a cut of 25 b.p. at its meeting this week is considered unlikely. This reluctance of the SARB to do what would be obvious to most is what makes this case study particularly compelling.

Real Bank Credit supplied and demanded by the Private Sector and the Real Economy. Monthly Data (2019=100)

SA; Real Short-term interest rates and Inflation 2020-2025. Monthly Data.

Source; Bloomberg and Investec Wealth & Investment

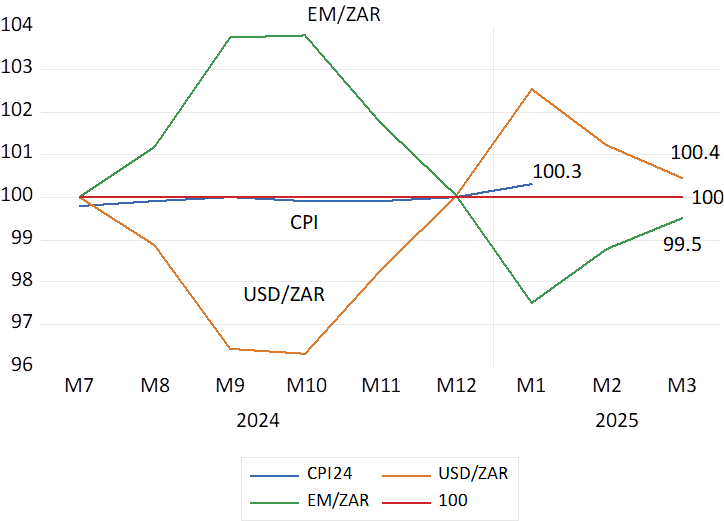

Some further facts might illuminate the case further. Why it should be asked has inflation come down so dramatically in SA? It is because spending (the demand side) remains depressed and because the supply side of the price equation has been especially helpful over the past year. It must be so given that exports and imports directly affected by the cost or value of foreign exchange are equivalent to 60% of GDP. And the ZAR has been unusually mighty.

Where the exchange rate goes so go prices – as has been the case in recent years. Rand weakness in 2023 led prices and inflation higher – and interest rates followed. Then strength in the rand since early 2024 has helped to largely stabilise the prices of imports and the CPI since mid-2024.

The ZAR Vs the USD and the EM Basket and the CPI. Lower number indicate ZAR strength. August 2024=100. Monthly Data

Source; Bloomberg and Investec Wealth & Investment

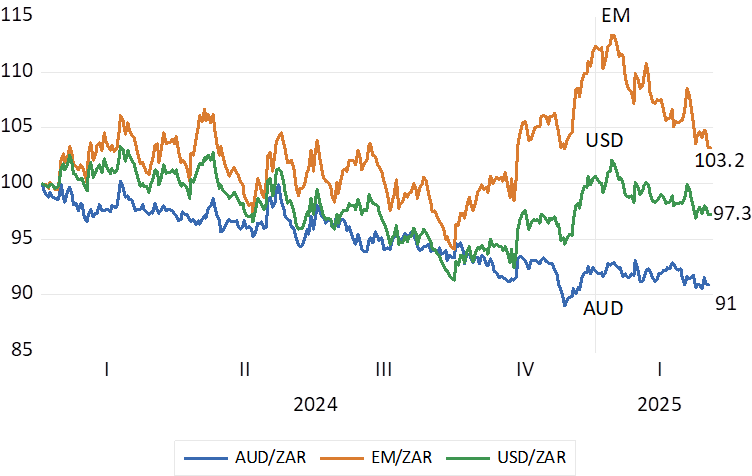

Exchange Rates; ZAR Vs the USD, Aussie dollar and EM Basket (Jan 2024=100) Daily Data

Source; Bloomberg and Investec Wealth & Investment

How then does one explain the behaviour of the rand- the single most important influence on the CPI? The introduction of the GNU improved the outlook for structural reforms and faster growth in GDP -and so improved the case for investing in SA to the benefit of capital flows and the rand. The biggest threat to fiscal sustainability in SA and to its bond market and so to the level of longer-term interest rates and debt service costs, is the absence of growth. Slower growth expected means a weaker rand and more inflation and more inflation expected and higher borrowing costs. And vice versa. The Reserve Bank contributes to growth via the influence of its interest rate settings on demand. The exchange rate nor therefore inflation is not under its direct control.

No doubt we will learn from the SARB about the global risks it has to contend with. But these are risks over which it has no predictable influence or the ability to predict confidently. Parliament and its decisions about the allocation of taxpayer’s money, especially to capital expenditure, will dominate the immediate outlook for growth and the ZAR. Inflation expected has only declined marginally in recent months. Yet again will be given by the SARB as a reason for not lowering interest rates further. But inflation expected can only recede with persistently lower inflation. That can only come with persistent rand strength. It too is beyond any direct control by the SARB.

The SARB focus should be on managing the demand side of the economy – using its interest rate settings to prevent too much spending that might lead prices higher and avoid too little spending that would depress growth. Which now means lower interest rates. It is simple logic.