The immediate challenge for the newly appointed SA cabinet is to do what it takes to stimulate faster growth in output incomes and employment over the next few years. And to instill a strongly held belief that they will succeed in doing so.

The benefits of any more optimistic belief that growth will accelerate would be immediate. The interest rate on longer dated RSA bonds would come down as the danger of a debt trap for SA receded. As it does with faster growth in tax and other revenues for the Republic.

Governments cannot formally default on the loans they issue in the local currency. But they may be tempted to pay down such debt by issuing more currency – should the interest burden on the debt become politically intolerable. Printing more money than economic actors are willing to hold, leads inevitably to more inflation as they get rid of their excess money holdings. Investors are very well aware of the process of inflation- led as it always is by governments unwilling to accept harsh economic realities.

Such inflationary dangers call for compensation for lenders in the form of higher interest rates. There is a lot of inflation priced into long term interest rates in SA that makes borrowing particularly burdensome for SA taxpayers. Very low interest rates of the kind now demanded of European and the Japanese governments, practically eliminates any possibility of a debt trap, even when the Debt to GDP ratios are more than double the ratio in SA, as they are. South Africa would look so much healthier were interest rates a lot lower.

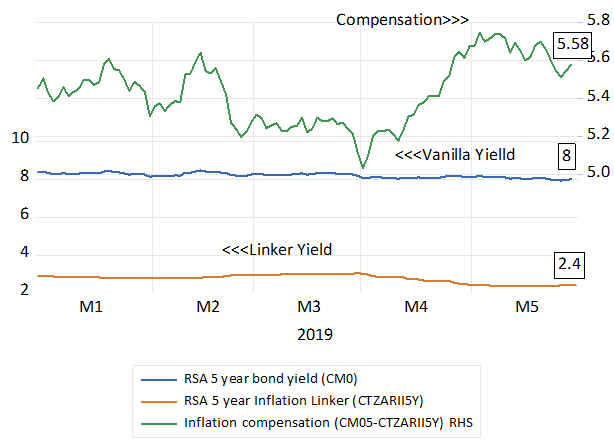

The running yields provided to match supply and demand for RSA bonds provides a very clear and continuous measure of how well the government is rated by investors for its ability to avoid inflation- and stimulate growth. The difference between the yield on a vanilla RSA bond and an inflation protected bond of the same period to maturity indicates how much inflation is expected by investors. It is a risk that the owner of an inflation linked bond largely avoids. Hence the difference between the yield on a five year vanilla RSA bond (currently around 8% p.a) and the lower yield on an inflation protected bond (currently 2.4% p.a) reveals that inflation in SA is expected to average 5.6% p.a. over the next five years and about 6.5% p.a. over the next ten years. Headline inflation is now significantly lower at 4.4% p.a.

Fig.1: RSA Bond yields and compensation for expected inflation (5 year bonds)

Source; Thompson Reuters, Bloomberg and Investec Wealth and Investment.

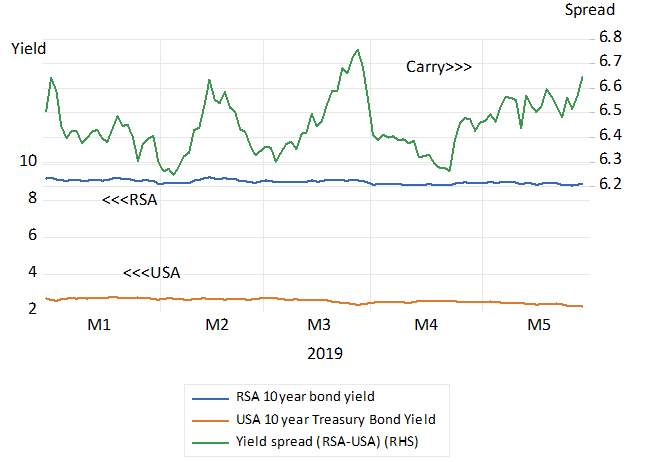

Another important signal comes from the difference between RSA rand bond yields and those on US Treasury Bonds of the same maturity. This spread indicates how much the rand is expected to depreciate over the years. The difference between 10 year RSA yields and US 10 year Treasury bonds is of the order of 6.6% p.a. That is the rand is expected to depreciate against the US dollar at an average over 6% p.a. over the next ten years. This clearly implies much more inflation in SA compared to the US- hence a further reason for much higher interest rates.

Fig. 2; RSA and USA Treasury Bond Yields (10 Year) Daily Data 2019

Source; Thompson Reuters, Bloomberg and Investec Wealth and Investment.

The very latest news from the RSA bond market has not been encouraging about the prospects for growth enhancing reforms. If anything these interest rates spreads have widened rather than narrowed – indicating more not less inflation expected and no more growth expected. Hopefully the selection of the cabinet members and better knowledge of their good intentions will raise expected growth and lower long-term interest rates. Unfortunately SA has not benefitted from the global decline in government bond yields as have other emerging market borrowers.

Fig.3 Global Bond Yields. Movement in May 2019.

The level of short-term interest rates will be set by the Reserve Bank. We can hope that the Bank will recognize that inflationary expectations are largely beyond their influence. More inflation expected can add upward pressure to prices as firms with price setting powers attempt to recover the higher costs of production they may expect. But such attempts to raise prices can be thwarted by an absence of demand for their goods and services.

Very weak demand for goods and services over which Reserve Bank’s interest rates have had a direct influence has contributed to very slow growth -and lower inflation. But without reducing inflation expected.

The Reserve Bank should recognize that lower inflation- achieved by deeply depressing spending and growth rates to counter more inflation expected- will not bring less inflation expected over the longer run. That is a task for the cabinet. The role for the Reserve Bank is to do what it can to stimulate more growth by lowering short term interest rates.

A post-script on debt management in SA

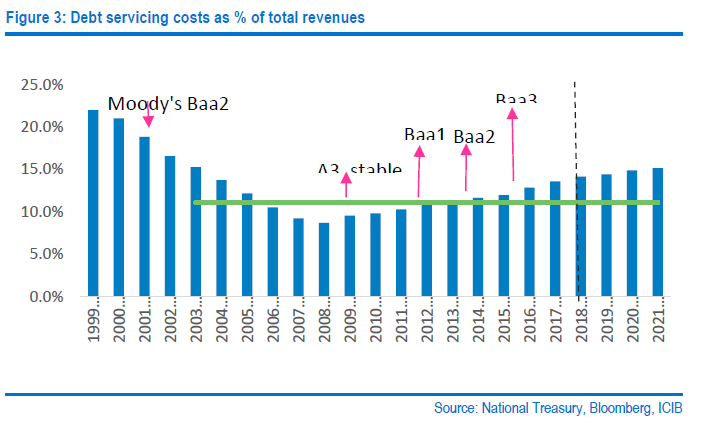

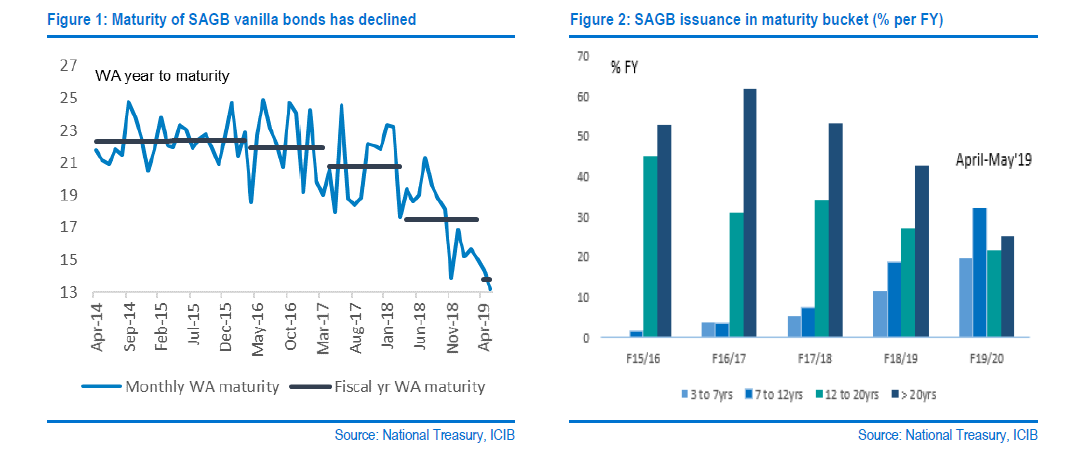

The SA Treasury has long adopted a policy to lengthen the maturity of RSA debt. The policy appears to have been reversed somewhat recently in response to the pressure on the budget placed by more debt funded at higher interest rates. We show the maturity structure of RSA debt issues in recent years below. We also show how debt service costs have risen as a share of tax revenues. [1]By international standards the duration of RSA debt is exceptionally high.

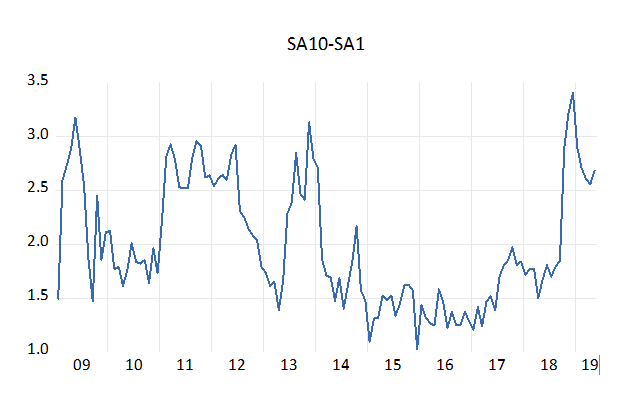

Borrowing long has been more expensive for the RSA than borrowing short. The term structure of rand denominated bond yields has been consistently upward sloping since 2008. The average monthly difference in these yields has been 2% p.a. between 2010 and 2019. See the figure below that charts the difference between 10 year and 1 year RSA yields.

Fig.4: The slope of the RSA yield curve RSA 10 year – RSA 1 year bond yields

The case the Treasury makes for extending maturities is to avoid the danger of so described roll over risk. The longer the maturity structure of the debt incurred, the less often has debt to be refinanced. Though surely the breadth and depth of the market for RSA bonds is surely enough protection against not being able to refinance debt when it comes due, or before it comes due. As are the large cash reserves the Treasury keeps with the Reserve Bank. Paying so much more to borrow long rather than short seems a very expensive way to avoid the unknown danger that it may be difficult to place debt at some unknown point in time.

But there is more than roll over risk to be considered. The Treasury preference for borrowing long- when inflationary expectations are elevated (over six per cent per annum as they have been for much of the period since 2010) – indicates little confidence in the ability of monetary policy to meet its inflation target of between 3 and 6 per cent p.a.

Borrowing long – extending the maturity structure of national debt -adds to the temptation to inflate away the real value of debt incurred. Investors are surely aware of their vulnerability to the consequences of a debt trap- the danger that a country will print money to retire expensive debt that will then lead to inflation and much reduce the real value of their loans.

Such reliance on borrowing long that brings with it inflationary temptation must show up in higher long term interest rates – relative to shorter rates- to compensate for the extra risks incurred in lending long. Having to roll over short term debt at market related interest rates that will rise with inflation makes lenders less hostage to the danger of unexpectedly high inflation. It may even act to discipline government spending and borrowing because inflating away the debt burden is not an option. Accordingly it reduces the danger of inflation and by doing so may improve a credit rating. Borrowing long is an opportunity that a government treasury should best resist- as proof of its anti-inflationary credentials.