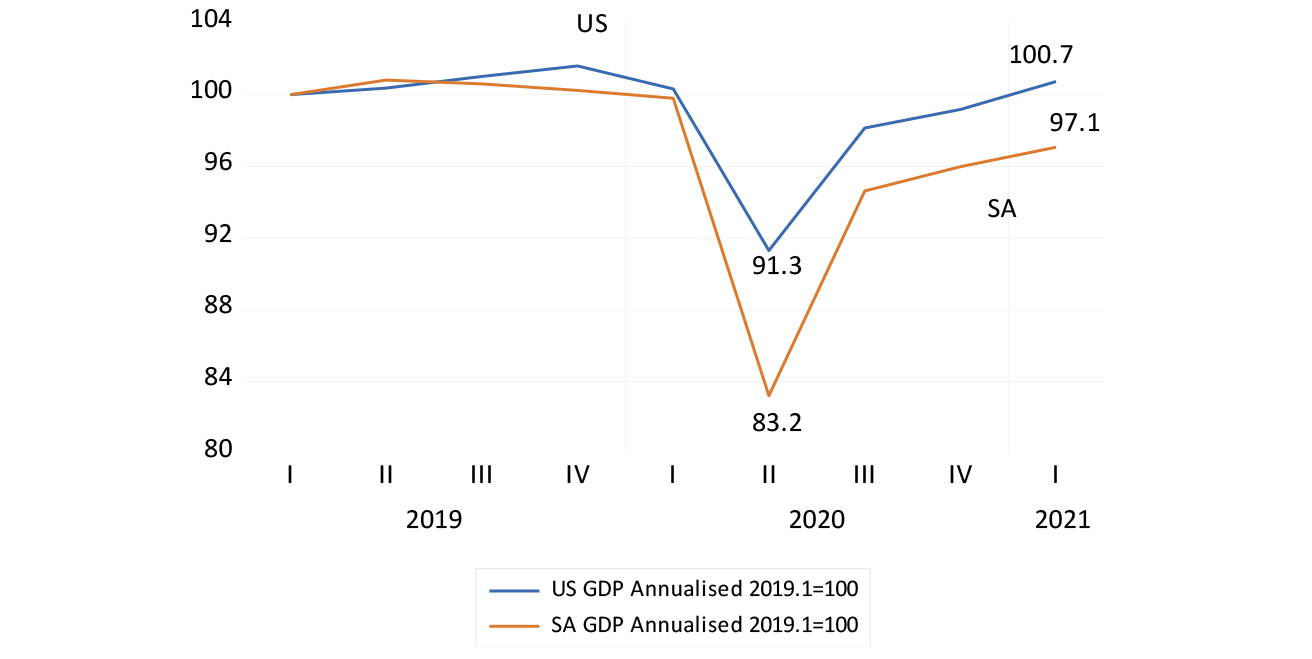

The steps taken in the US to counter the destruction of incomes and output caused by the lockdowns of economic activity can be regarded as a resounding success. Real US output is now ahead of pre-covid levels. By the end of 2021, GDP could well surpass the GDP that might have been expected absent the lock downs. It took a great deal of income relief in the form of cheques in the post from Uncle Sam, supplemented by generous unemployment benefits and relief for businesses.

The extra income means an increase in deposits, in other words money placed with the US banks, to be spent later or exchanged for other financial assets.

Deposits held by banks with the Federal Reserve System have increased by 85%, and deposits at the commercial banks have grown by 26% since March 2020. The source of the extra cash, the deposits at the commercial banks and the Fed, has been additional purchases of government bonds and mortgage-backed securities in the debt markets from the banks and their clients, which are being maintained at the rate of US$120bn a month.

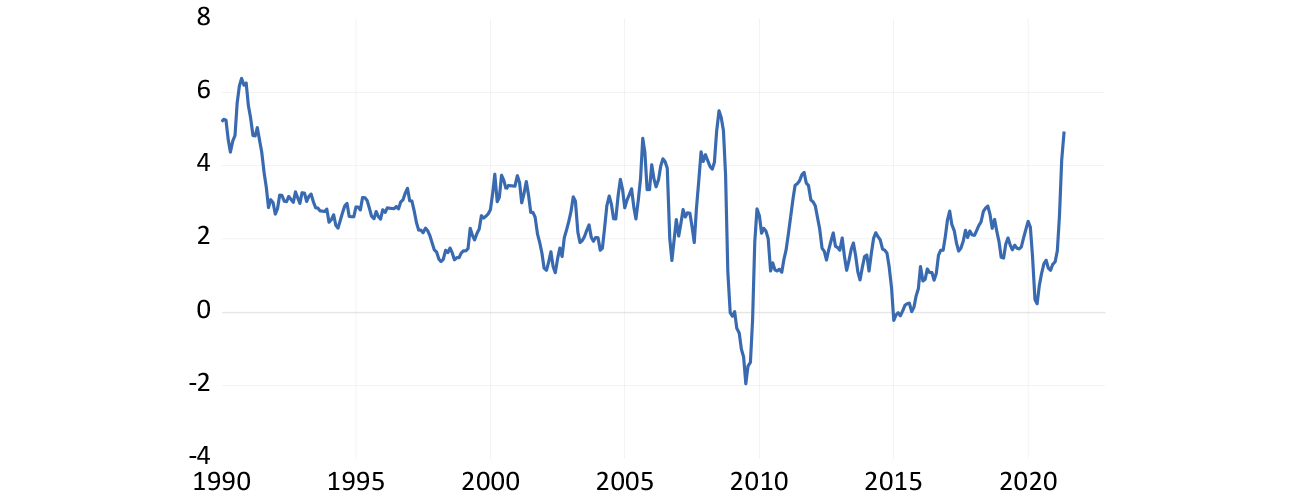

The assets and the liabilities of the Fed have increased by 36% over that period. This is money creation on an awe-inspiring scale and it has worked, as intended, to promote demand for goods and services. Providers of goods and services are struggling to keep up with demand, while also struggling to add to payrolls, leading to upward pressure on prices. The US CPI was up by 5% in May – a rate of inflation not seen since 2008 and before then only in the 1990s.

Inflation in the US – annual percentage changes in CPI

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis and Investec Wealth & Investment, 15/06/2021

However, the outlook for inflation in the US is less obvious than usual. The Fed has been surprised by the pick-up in the inflation rate, as was indicated by the Federal Open Market Committee and Fed chief Jerome Powell’s press conference on 16 June. Powell remains confident that the increase in inflation is transitory and the Fed does not intend raising interest rates any time soon, at least not until the economy has returned to full employment, which is judged to be some way off.

(It should be noted that full employment may mean a lower number than previously estimated, given that two million potential workers have withdrawn from the labour market since the lockdowns. They may however wish to return to employment should the opportunities to do so present themselves; this is one of the uncertainties the Fed is trying to deal with as it looks to understand the post-Covid world.)

A number of Fed officials however have brought forward the time when they think the Fed will first raise its key interest rates, to the first quarter of 2023, a revision that surprised the market and moved long-term interest rates higher. The bond market nonetheless remains of the view that inflation in the US over the next 10 years will remain no higher than the 2% average rate targeted by the Fed. The Fed will be alert to the prospect that more inflation than this will arise.

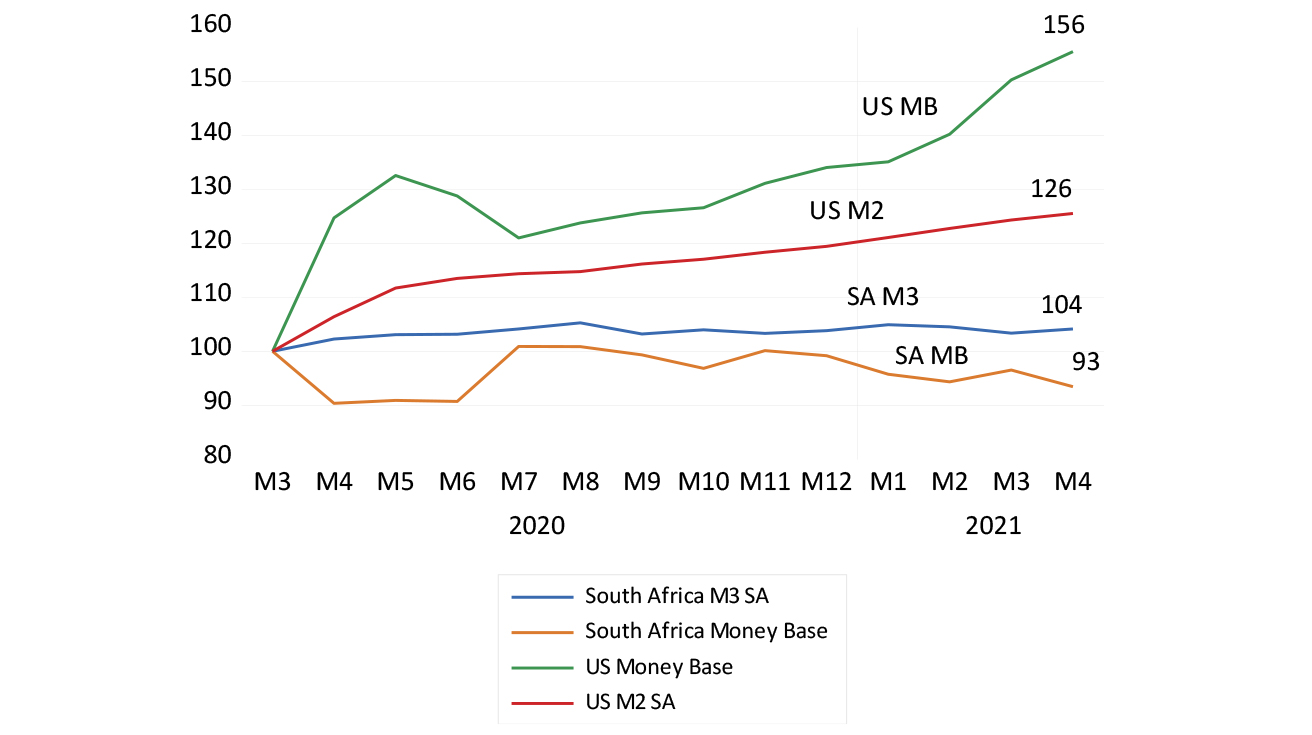

A tale of two central banks

The contrast of the actions of the Fed with those of the South African Reserve Bank (SARB) is striking. The SARB balance sheet contracted by R115bn, 10.8%, between March 2020 and May 2021. Since January 2020, the sum of notes issued plus deposits of the banks with the SARB (the money base) has declined by 6%, the supply of bank deposits (M3) has grown by a paltry 4% and bank credit by 2%. These are shocking figures for an economy struggling to escape a deep recession.

The SARB may be of the view that money and credit are less important for the economy, and that changes in interest rates are the only instrument they have to influence the economy.

Monetary comparisons between SA and the US (March 2020 = 100)

Source: SA Reserve Bank, Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis and Investec Wealth & Investment, 15/06/2021

The SARB seems to believe their lower interest rate settings have been accommodative and helpful to the economy. Higher interest rates would, of course, have been unhelpful and lower rates were certainly called for. However, the money and credit numbers indicate deeply depressing influences on the economy, influences that the SARB could and should have done much more to relieve, following the US example. There is more to monetary policy and its influence on the economy than movements in interest rates.

GDP in the US and SA (March 2000 = 100)

Source: SA Reserve Bank, Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis and Investec Wealth & Investment, 15/06/2021

It would be easy to despair of the prospects for the SA economy given the current, discouraging trends in the supply of money and credit. However, we can draw hope from the possibility that the US cavalry (with some Chinese assistance) will rescue us, in the form of rising prices for metals and minerals that are very much part of the inflation process currently under way in the US.

Metal prices have always led the SA business cycle, in both directions. They may well lead us out of the current morass, after which the supply of money and credit will then pick up momentum to reinforce the recovery, as they have always done in a pro-cyclical way. The responses to the lockdowns have made it clear how our monetary policy reacts to the real economy. A favourable wind from offshore may lift the money supply and bank credit, without which faster growth is not possible.