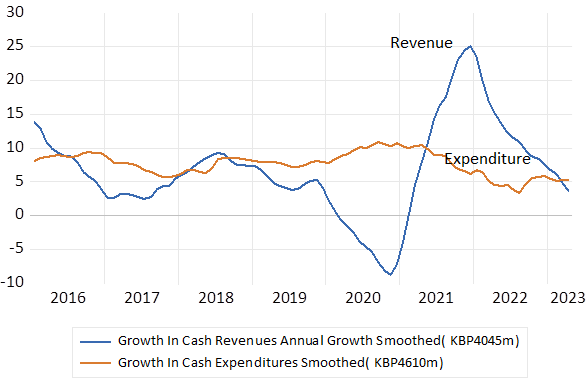

An unexpected shortfall in SA government revenues, has provoked something of a fiscal contretemps. R60b less revenue than was estimated in the February Budget has followed an even larger windfall in 2021 linked to the post Covid inflation of metal prices. The recent pull back in metal prices and in mining company profits has seen government revenues falling back sharply from peak growth rates of 25% in late 2021 to zero growth. Government expenditure has stayed on an essentially modest growth tack of about 5% p.a.

Recent Trends in SA National Government Revenues and Expenditure. Growth smoothed Y/Y

Source; SA Reserve Bank and Investec Wealth and Investment

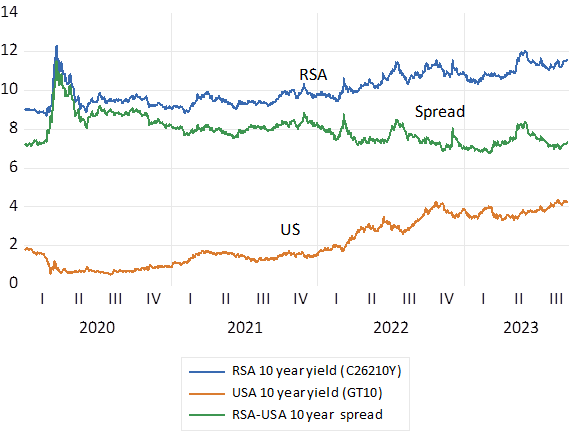

Less revenue means more borrowing. South African taxpayers are already paying a high price for our highly compromised credit-rating. We pay an extra 2.7% p.a. more than Uncle Sam to borrow US dollars for five years. And a rand denominated RSA five-year bond offers investors 5.5% p.a. more than a US Treasury of the same duration (9.89-4.39) The spread on a ten-year RSA over the US Treasury yield is even higher, over 7.3 % p.a. (11.57-4.25). The reason for such expensive, after expected inflation, borrowing costs and risk spreads is the persistent skepticism of potential investors in SA bonds, local and foreign, about the willingness and consequences of South Africa having to live within the limits of government revenue- heavily constrained as it is expected to be – by very slow growing GDP. The further forward lenders are asked to judge our growth prospects and fiscal policy settings, the wider have been the risk spreads and the higher the cost of issuing long dated debt.

RSA and USA 10 year bond yields and risk spread.

Source; Bloomberg and Investec Wealth and Investment

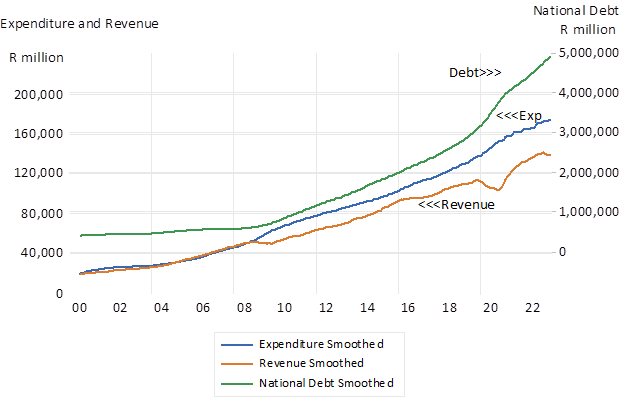

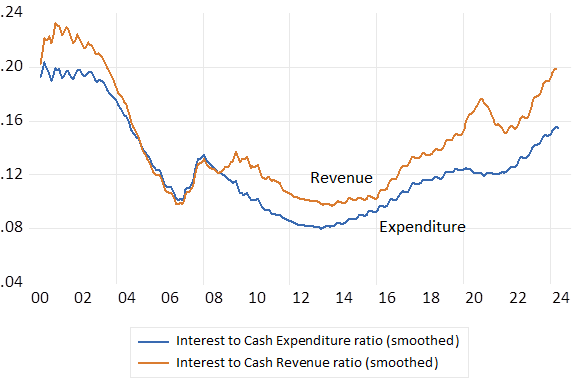

Yet if it is a crisis in the bond market (not immediately obvious given modest recent interest rate movements) the heavy burdens of raising debt for the SA taxpayer has been a long time in the making. SA national government revenues have consistently lagged government spending- by a per cent or two each year ever since the recession of 2010. And the Covid lockdowns were naturally much harder on revenues than government expenditure. These difference between revenue and expenditure have had to be covered by large extra volumes of additional government borrowing. The share of interest paid by the national government in revenues and expenditure has been rising sharply, doubling since 2014. Interest paid in serving the national debt is now 20% of all national government revenues and about 16% of all expenditures. It is not the kind of expenditure that helps win elections.

SA Government Revenue, Expenditure and Debt

Source; SA Reserve Bank and Investec Wealth and Investment

Share of Interest Payments in National Government Revenue and Expenditure

Source; SA Reserve Bank and Investec Wealth and Investment

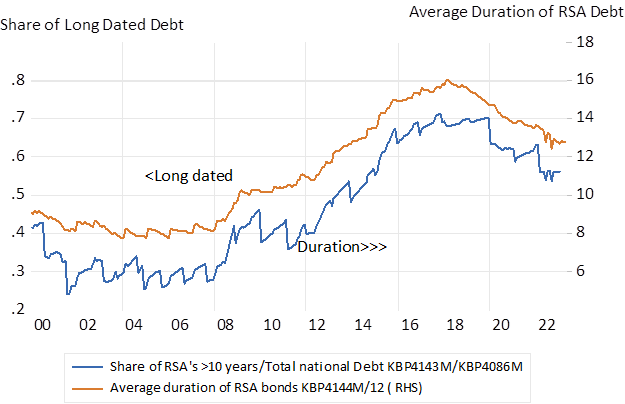

The share of RSA debt of more than ten years to maturity rose strikingly from 30 to over 70 per cent of all national government debt between 2008 and 2020 – at inevitably much higher rates. The government could immediately relieve part of the burden of high interest rates by reducing the extraordinarily long duration of RSA debt. As indeed it has been doing since 2018.

The extended duration of RSA debt. Long dated debt as share of total debt and average duration of all debt in years (Monthly data)

Source; SA Reserve Bank and Investec Wealth and Investment

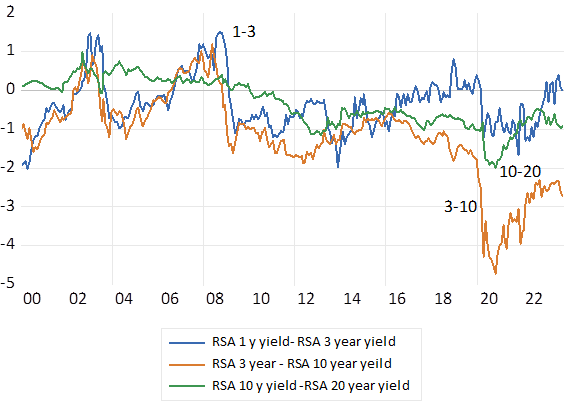

RSA Bond yield differences- by duration of debt

Source; Iress and Investec Wealth and Investment

It was a form of hubris to think that lenders would be willing to take a twenty year and longer view on the fiscal outlook for SA on reasonable terms. The long-term lender is highly exposed to inflation and default through inflation, that the short-term lender largely avoids. The benefits of borrowing long are apparently that it avoids the risks that rolling over short-term debt that may prove to be difficult at inconvenient moments in the money markets. But this makes even less sense when the SA Treasury was building its cash reserves at the Reserve Bank from R70 billion in early 2010 to R183 billion by January 2023.

Managing the interest burden of national debt can play a small part in solving the problem of slow growth for the SA government. Even should government and private spending in real terms remain as deeply and unpopularly constrained as it is likely to be this year and next. Only faster growth can avoid the interest rate trap as interest paid/all government spending should rise further. Absent growth the burden of paying interest, rather than undertaking other forms of spending, is very likely to make a resort to money creation, as an alternative to more borrowing, irresistible. The growth enhancing choices for economic policy should be obvious. There is really no other way.