Bond markets: Operation twist in reverse, or just bowling a wrong ‘un?

The US Federal Reserve System has been conducting operations to reduce the interest yield on long dated US Treasury Bonds, and by so doing attempting to twist the yield curve, that is buying longer dated bonds in order to reduce long term interest rates.

Meanwhile in SA, we are seeing something of a twist in reverse. We will discuss this topic further in this piece, but first some explanation of the US version.

The Fed has been borrowing short from its member banks to buy long dated US government debt. It has committed some US$400bn to the scheme. The Fed owns about US$1.675 trillion of US government debt or over 10% of all US debt in issue. It also holds US$841bn of mortgage backed securities issued by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the government sponsored enterprises that support the mortgage market in the US. The Fed has been buying these securities in the market and the sums paid out have mostly ended up as excess cash reserves (deposits) held by banks with the Fed itself. What the Fed pays out has ended up with the Fed.

Mortgage loans in the US are typically long dated loans for up to 30 years, at fixed rates of interest linked to the yield on long dated Treasuries. The intention of the Fed is to reduce mortgage rates to encourage demand for homes and house prices. By so doing it would encourage a recovery in home building activity. Higher house prices would also help US households recover some of the equity they have lost in their homes.

According to US Flows of Funds Accounts published bty the Fed, the average US home is worth 30% less than it was in 2006. In 2005 homeowners’ equity in their homes (the difference between the market value of their homes and their mortgage liabilities) was worth over $13 trillion. The value of this equity had shrunk to $6.2 trillion by September 2011 and the share of owners’ equity in their homes from 59.8% to 38.6%. The net worth of US households has held up much better than their equity in homes over this period, having declined marginally from over $59 trillion in 2005 to $58.7 trillion in 2011. This represents 5.1 times the disposable incomes of households, which is a very high wealth to income ratio by international standards.

Without a recovery in the housing market, the prospects for US economic growth cannot be regarded as promising: hence Operation Twist. Long term interest and mortgage rates have remained exceptionally low, presumably mostly attributable to the safe haven status of US government debt in a highly risk averse world, rather than to Operation Twist itself or the quantitative easing (purchases of bonds and other securities) already conducted by the Fed.

And so to the reverse

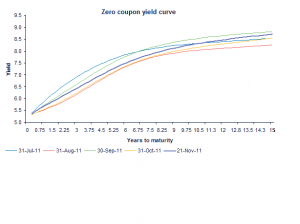

The SA Treasury has also been conducting its own intervention in the market for SA government debt. This may be described as the reverse of operation twist. The Treasury has been very busy extending the maturity profile of RSA government debt, actively buying up short dated government securities before due date and issuing much long dated securities of both the conventional and inflation linked variety. With the yield curve in SA upward sloping and getting more so (see below) this means that for now, or until the yield curve turns flat or negative, the SA taxpayer is paying up to 2% per annum more for its longer term borrowing. This additional expense of servicing interest bearing domestic rand denominated debt of the order of R800bn might well be better incurred helping the poor or giving tax relief to businesses to employ them. Why then the rush to roll over RSA debt before it matures and especially to convert lower interest short term debt to higher longer dated debt, before it is required to do so?

Source: Investec Securities and Investec Wealth and Investment

The average duration of SA debt, that is the time it takes for investors to recover their capital through a mixture of coupon payments and principal repayment, has risen significantly over recent years as we show below. Zero coupon bonds issued at a discount have a duration equal to the time to maturity. For debt with a predetermined coupon, the higher the nominal coupon payment, the shorter the duration. The average duration of US government debt is shorter than RSA debt – somewhere between four and five years.

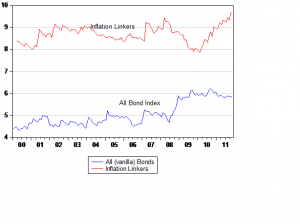

Were these refinancing operations of the SA Treasury being conducted in the vanilla bonds alone, one might conclude that the Treasury, in preferring long to short, had a negative view on the inflation outlook for SA. Borrowing long is a good idea when inflation turns out to be unexpectedly high – borrowing short makes sense when the market overestimates the inflation rate incorporated into long term interest rates.

However the opposite is true when issuing inflation linkers and the Treasury has been especially aggressive converting its short dated inflation linkers into much longer dated inflation linkers. If inflation was expected to rise above expectations, an issuer would much prefer issuing short dated inflation linked securities, rather than the longer dated maturities. These long dated linkers would bring ever higher interest payments and receipts as inflation rose.

At recent auctions the Treasury has been issuing inflation linkers with 20 years to maturity (for example the R202) at real yields of 2.6% to redeem the once dominant R189 that is due to mature in 2013. The R189 is currently priced to offer a negative real yield of -0.07%. Or in other words, the Treasury is now paying out something like 240bps extra to roll over this inflation linked debt, rather than waiting for this shorter term debt to mature in two years time.

Average duration of RSA Inflation and Vanilla Bonds

Why Europe is not a good example

Why then would the Treasury be pursuing such aggressively expensive debt management? Hopefully it is not in response to the difficulties European governments and their debt managers have been seen to have in rolling over their debt with highly bunched maturity schedules. These refinancing difficulties arise because the Greek, Portuguese, Italian and Spanish governments cannot call upon the services of their own central banks to convert, without limit, interest bearing into non-interest bearing government debt- that is to say cash. Their central bank sits in Frankfurt and appears very reluctant to convert longer dated Euro debt into cash. This is not a problem for the US. If faced by any temporary reluctance to bid for longer dated Treasuries, the Fed could come to the rescue with extra cash.

So could the SA Reserve Bank, if called upon, issue rands in exchange to overcome any refinancing emergency that might show up. Rolling over debt can only become a solvency or liquidity problem when the borrowing is undertaken in a foreign currency. Rolling over debt cannot be an issue when the debt is issued in an inconvertible currency that can be created without limit by a central bank should this be forced upon a government with its independent central bank. And most important, the knowledge that in last resort, government debt issued in the inconvertible currency of the land can always be converted in to cash, would surely be enough to fully overcome fears that government debt could not be rolled over. By exchanging cash for government securities (if conducted without limits), a central bank could invoke an inflation problem. However it could also overcome any refinancing problems (as the Italians and Greeks, now without such a fallback position, are fully aware).

There is presumably a case for smoothing what may be bunched repayment schedules for maturing government debt. But there is also a case for anticipating them in advance when scheduling debt, to avoid bunched repayments making such smoothing operations unnecessary in the first place. Paying a large interest premium to do so does not make good sense; nor is long dated debt issued by the RSA necessarily superior to issuing shorter dated debt.

Long term interest rates are the geometric average of expected short rates over the same period. To think otherwise is to second guess the market in fixed interest and there is little reason to believe the issuers of debt have superior insight about the direction of interest rates than lenders have. There are however some unintended consequences of longer duration: the longer the duration the more responsive the All Bond Index will be to unexpected changes in interest rates. Adding risks to fixed interest rate bonds in general discourages demand for them.

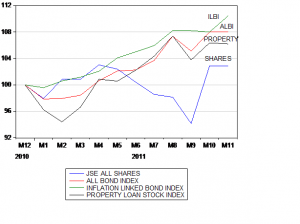

Furthermore the recent debt management operations in the inflation linkers (which have meant additional demand for them) have made this class of bonds an outperformer over the past year. Is the SA Treasury, in its urgency to substitute long dated for short dated RSA securities (to avoid what it regards as potential embarrassments in the debt market), misreading the nature of the Euro debt problems – at the expense of the SA taxpayer? Brian Kantor

Asset Class Performance 2011 to November 18th