The equity markets late yesterday in Europe and also late in the New York day made a spectacle of themselves and it was not a pretty sight at all, especially when the futures on the DJ Industrials and S&P 500 moved sharply higher after the close. The biggest losers (on a day that saw the major markets down by more than 4%, having been up by the same percentage more or less the day before) were the European and US banks.

SocGen, a major French bank, was down over 26% by the close of the trading day on rumours, soon denied, that French sovereign debt was about to be downgraded by the rating agencies. BNP Paribas lost 11% on the day and Credit Agricole almost 15% off. On the other side of the Atlantic, Bank of America was down another 10.9% while Citi and Goldman Sachs both lost 10.5% on the day. JPMorgan escaped relatively lightly with a 5.6% loss and Wells Fargo was down 7.7% on the day.

We have pointed out before that no national bank can hope to survive the default of its sovereign, or even in some senses, the serious expectation of its default if it were forced to revalue its assets at their reduced market value. This is because the presumed safest part of the banks’ balance sheets are committed and required by banking rules to be invested in significant proportions in sovereign debt.

The way governments and their banks usually avoid notional default on their debts is by printing money. This may mean more inflation, but also avoids banking failure since the banks’ assets and their liabilities also inflate more or less to the same degree.

The European Central Bank (ECB) is the only central bank in the euro system with the power to print euros. It continues to demonstrate a degree of reluctance to do so, out of fear (or perhaps German fears) of providing an easy way for European governments to get out of their fiscal crises and so avoid the necessity of cutting spending. The reality is that the ECB will have no alternative but to buy the bonds of threatened European governments if a banking crisis is to be avoided; or to indicate that it would be prepared to do so aggressively if called upon. Such unambiguous intentions might in themselves be more than enough to put the bond and bank short sellers to flight. The primary purpose of any central bank is to avoid a financial crisis and to use its considerable (and essential) power to print money without limits in order to prevent crisis. Further, when circumstances permit, they have the power to take the cash back again, usually with the profits that come with crisis resolution. The actions taken by the US Fed to pump money into the US financial system not only saved the system but did so at a profit to taxpayers. The ECB no doubt is well aware of this responsibility. Exercising it with vigour is well overdue. After all, financial instability is a threat not only to the financial system but to the real economy.

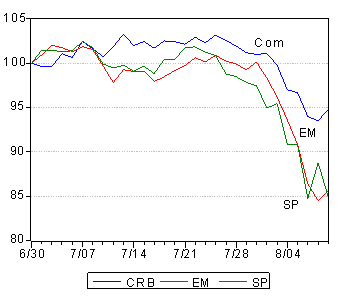

It is of interest to note that the emerging equity and the commodity markets (and so the rand) after having been engulfed by global fears on Monday, actually ended yesterday higher rather than lower. The volatility yesterday was clearly a crisis of confidence in European banks and in the willingness of the ECB to deal with it rather than new fears about the global economy. Commodity markets in general, as represented by the Reuters CRB Index can be regarded as having survived rather well the recent revival of risk aversion