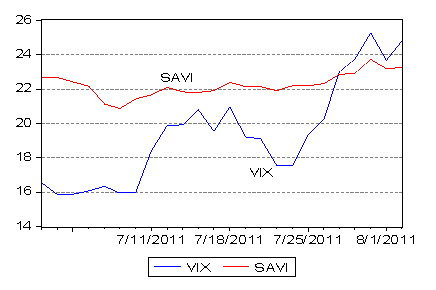

The world as reflected in equity markets has become a riskier environment. Day to day and even intraday, share price movements have become more pronounced (volatility or risks rising) with an inevitable and distinct downward bias. The outlook for the global economy has become more uncertain and this uncertainty has been demonstrated in the form of lower and more volatile valuations. In the figure below we show how much daily percentage moves in the S&P volatility indicator, the VIX, and daily per cent moves in the S&P 500 have increased over the past week.

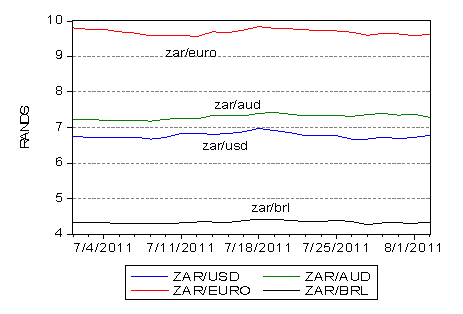

In a clearly riskier environment such as this, a degree of rand weakness might have been expected. In fact the rand has held up very well against not only the US dollar and the euro, but also the Aussie dollar and the Brazilian real.

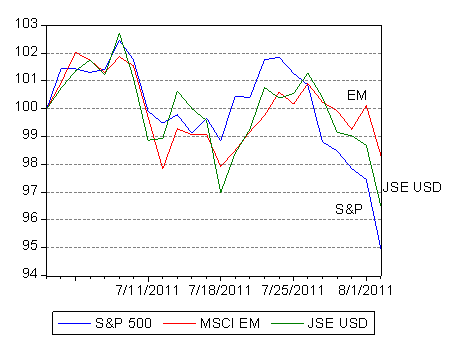

The explanation for these unusual currency events – the rand strengthening in a riskier environment – deserves an explanation. The explanation is to be found in the behaviour of emerging equity markets from which the JSE and the rand take their cue. Emerging equity markets have held up better than the US market. It may be seen that this quarter and particularly this week, the emerging market (EM) Index has declined less than has the S&P 500. The average EM market by the close on 2 August was off by a mere one and a half per cent compared with 30 June. The S&P 500 had lost nearly 5% over this period and the JSE about 3% in US dollars.

Moreover the emerging markets have not been as volatile as the New York equity markets. The volatility priced into options traded on the JSE represented by the SAVI is now less than that of volatility priced into the S&P 500, as represented by the VIX that.

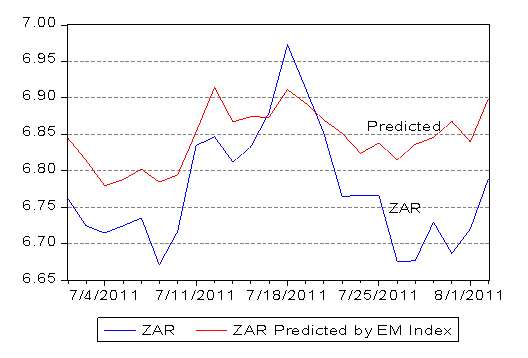

And so when we run our model (utilising daily data since January 2009) to explain the rand/US dollar exchange rate with the EM Equity Index, the model predicts a rand/US dollar rate of R6.90 compared with an actual R6.80 on 2 August.

The enhanced risks therefore may be recognised as more uncertainty about the outlook for the US economy than anxiety about the prospects for emerging market economies (as well as the companies that serve them, including those listed on the JSE). This makes every sense. It is the developed world that needs to get its fiscal house in order, not the emerging economies that are mostly in comparatively good economic and fiscal shape.

Perhaps the agitated state of the developed equity markets indicates that there is now even less confidence in the ability of the Obama administration to sustain faster US growth, given the shenanigans that accompanied the lifting of the US debt ceiling. It was not the President’s nor his party’s finest hour.

It is surely up to President Obama to prove that the market is misjudging him. But he has little time to prove the market wrong before facing the US electorate in November 2012. To build the confidence that would revive spending plans of firms and households and employment, he would need to convince Americans that he can implement a realistic long term plan to deal with the US deficit without raising tax rates. Faster economic growth is essential to this purpose. Such a plan would have to include critical features like reining in the threatened runaway government spending on medical benefits under Obama care. This will not come easily.