19th January 2022

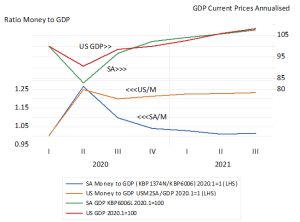

Fiscal and monetary policy in the US and SA will command close attention in 2022. The US will be expected to adjust to the success it has had overcoming the Covid threat to its economy. Success has led to excess in the form of much higher rates of inflation. Larger fiscal deficits, that approached 16% of GDP in late 2020 were incurred to supplement incomes with checks drawn on the Treasury has seen the Federal debt to GDP ratio rise to 128% of GDP. Consequently the ratio of money (bank deposits) to incomes (GDP) is now 25% higher than they were before Covid. This huge stock of money will continue to be exchanged for other assets and for goods – and services -when the time is right. The money will not go away – it will merely lose more of its real value as prices – including asset prices – rise further at the inflation rate.

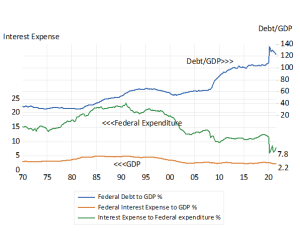

It is a question of how much and how quickly interest rates go higher to restrain spending. Longer term interest rates may rise should inflation be expected to rise permanently to higher levels – which is not yet the case. The problem with higher interest rates is that they have important fiscal implications. Paying higher market determined interest rates to keep the bond market open to issues of more government debt – takes away from other spending – it may demand higher taxes or less government spending – not well suited to make governments popular.

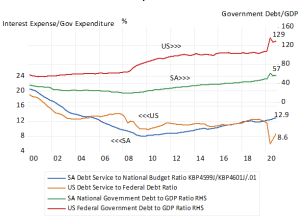

The US, given the currently low cost of raising debt, remains in a favourable fiscal setting. The average yield on all federal debt is below 2%, while the debt service ratio – the ratio of interest paid to the Fed budget – is below 9%. It was about double that rate in 2000 when the debt to GDP ratio was about 50% Every-one per cent increase in the average cost of funding the US debt, means an extra 250 billion dollars of interest to be paid out – on top of the current 500 billion payments. It will require a resolute, politically independent and inflation fighting central bank to tame inflation. (see figure below)

US Fiscal Trends

The comparisons of SA with the US are not alltogether unfavourable. The national debt to GDP ratio is much lower – only about 60% The debt-service ratio is significantly higher equivalent to 13% of the national budget. it was over 20% of the budget in 2000. The average yield on all RSA Treasury debt has gradually fallen to about 6%. It was 10% in 2008. (see figure below)

SA and the US – some fiscal comparisons

Source; Federal Reserve Bank of St.Louis, South African Reserve Bank, Investec Wealth and Investment

The SA Reserve Bank did not (wrongly in my view) do quantitative easing. The broader money supply has hardly grown at all since early 2020. The money to GDP ratio has fallen back to where it was before Covid. (see below) There is no excess demand.

South Africa and the US – some money and GDP comparisons

Source; Federal Reserve Bank of St.Louis, South African Reserve Bank, Investec Wealth and Investment

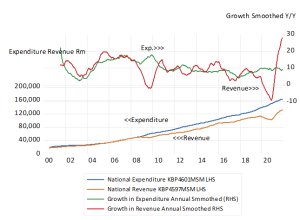

Of further relevance is that SA Government Revenues have been growing significantly faster than government expenditure. Thanks to the global inflation reflected in higher metal and mineral prices leading and much improved and taxable mining incomes. Both monetary and fiscal policy settings therefore remain austere. They explain why the economy is growing so slowly.

South Africa Fiscal Trends

Source; South African Reserve Bank, Investec Wealth and Investment

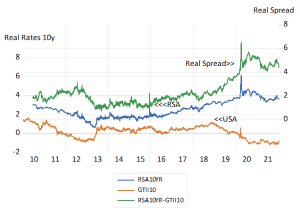

The problem is that our market determined credit ratings have remained unchanged and our cost of raising long term debt very expensive. The RSA pays about 8% more for ten-year money than the US. Even more discouraging is the extra real 4% we offer on long dated inflation protected bonds.

SA Interest rates and risk spreads

Source; Bloomberg, Investec Wealth and Investment

Every-one per cent move in our government borrowing costs- would be worth an extra R37b a year to the Treasury. Lower interest rates would also reduce the returns required by businesses and help revive what is a very depressed rate of capital expenditure. The world of bond investors demands compensation for the danger that SA will sooner or later confront a debt-service trap from which printing money, and the accompanying debt destroying inflation, might be the preferred escape. They are much more generous to the US.

It is fundamentally the failure to grow faster that puts government revenues and Budgets at risk. The best SA can do this year to lower borrowing costs would be to sustain smaller fiscal deficits. And for the Reserve Bank to recognize that growth- not inflation – is the SA problem- and to set short-term interest rates accordingly. To help keep debt service costs down and improve the government revenue line.