The Rolling Stones captured the disillusion of the 1960s counter culture in their hit song “You Can’t Always Get What You Want”. It was released in 1969 after the initial wave of 1960s optimism had surged to anger and disenchantment. The song offers practical hope by suggesting that we should strive to get what we need since we’re bound to fall short in getting what we want.

The platinum industry has been one of great hope and now disillusionment. Has it been profitable and created value? Is it profitable today and what is implied in the share prices of platinum mining companies? By answering these questions, we can begin realistically to untangle economic wants and needs.

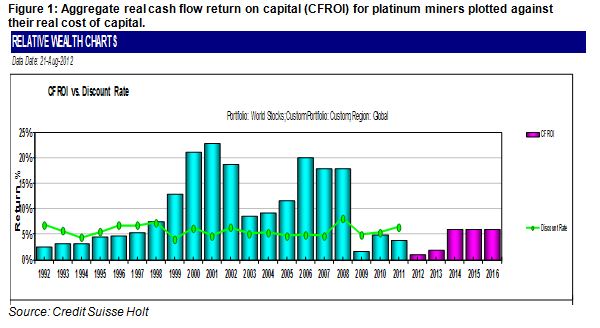

We’ve aggregated the historical financial statements of the four largest platinum miners (Anglo American Platinum, Impala, Lonmin and Northam) and calculated the inflation-adjusted cash flow return on operating assets, CFROI®. From 1992 to 1997, platinum miners were generating an unattractive return on capital, which slipped below the cost of capital. The years 1999 to 2002 provided the first wave of extraordinary fortune for this industry. The real return on capital exceeded 20%, making it one of the most profitable industries in the world at that time. The rush was on to mine platinum and build company strategies around this effort. Lonmin bet its future on platinum.

The second wave of fortune occurred during the global commodities “super cycle” from 2006 to 2008. Again, platinum mining became one of the most profitable businesses in the world as shown in our chart. The good times ended abruptly with the onset of the Great Recession in 2009, and platinum miners saw their real return on capital drop below 2% – well below the cost of capital, i.e., the return required to justify committing further capital to the industry.

Unfortunately, operating returns have not improved much and have remained below the cost of capital throughout the global slowdown due to increasing labour and excavation costs, and lower platinum prices. Suffice to say, platinum miners aren’t producing sufficient returns to satisfy shareholders. This has resulted in cost-cutting, lay-offs and chops to capital expenditure plans. These are natural economic consequences when a business is destroying economic value by not meeting its cost of capital.

And what does the future hold? We’ve taken analyst expectations for 2012 and 2013 and estimated the real return on capital. It remains very poor at a wealth destructive level of 2%. There is no hint of a return to superior profitability in the share prices of platinum miners. At best, the market has them priced to return to a real return on capital of 6%, which is the average real cost of capital.

It looks highly unlikely that platinum miners will be able to satisfy the wants of their stakeholders. All parties should focus on what is realistically possible and economically feasible. The workers and the unions already subject to retrenchment and very poor job prospects would surely be wise to focus on job retention rather than further gains in real employment benefits. Though grave damage to employment prospects in what was once a promising industry has surely already been done, northern Europe’s response to the Great Recession remains a potential template for management and labour. The cold reality is that capital in the form of increasingly sophisticated and robotic equipment will continue to replace labour. Management will have had their minds ever more strongly focused on such possibilities by recent events.

Moreover, SA has a responsibility to the global economy to supply platinum in predictable volume: the motor industry depends on this. Higher platinum prices, while a helpful short term response to disrupted output, would encourage the search for alternatives to platinum for auto catalysts. This would mean a decline in platinum prices over the long term.

Unless the industry can come to deliver a cost of capital beating return, its value to all stakeholders will surely decline. Perhaps they will even decline to the point where nationalising the industry with full compensation might seem a tragically realistic proposition.

Nationalisation will not solve the problem of poor labour relations and the decline in the productivity of both labour and capital in the industry. It would simply mean that taxpayers, rather than shareholders, carry the can for the failures of management. To its financial detriment, government would have to invest scarce funds in a capital-intensive industry that is not generating a sufficient return. Workers might think management (subject to the discipline of taxpayers rather than shareholders) would be a softer touch, but this would lead to the spiral of greater destruction of economic value and ultimately fewer jobs. Government and taxpayers should be very wary of signing a blank cheque. All parties need to focus on what is realistically possible and economically feasible. David Holland* and Brian Kantor

*David Holland is a senior advisor to Credit Suisse and was previously a Managing Director at Credit Suisse HOLT based in London in charge of the global HOLT Valuation & Analytics group.