The Naspers value gap (net asset value less market value) has narrowed significantly since the restructuring – which will see a Newco being listed in Amsterdam – was announced to the market. What does this mean for shareholders?

The proposed restructuring of Naspers, first mooted in March and now confirmed in a circular to shareholders on 29 May, has been favourably received by the market. The intention is to restructure Naspers into two linked companies: a Newco (to be named), with a primary listing in Amsterdam and a secondary listing on the JSE, and a new Naspers with its primary listing still in South Africa.

The Newco will hold the international assets of Naspers, including its 31% of Tencent, and will focus on global opportunities. The South African Naspers will have a 73% share of the Newco, will hold the local assets of Naspers and will also pursue investment opportunities – presumably mostly in South Africa.

Naspers shareholders in absolute terms were, at the start of June, about R120bn better off than they were three weeks previously, according to calculations by my colleague Thane Duff of Investec Wealth & Investment. The Naspers share price has outperformed that of Tencent recently.

To explain, the large gap between the net asset value (NAV) of Naspers (the sum of its parts of which the holding in Tencent dwarfs all the others) and the market value of Naspers (now R1.462 trillion rand) has narrowed by as much as R120bn in recent weeks.

This value gap (NAV less market value – which we can describe as the difference in the value of Naspers were all its assets unbundled to shareholders and its value as an ongoing business) however, remains a considerable R386bn. The value of the Naspers holding in Tencent is currently worth 127% of the market value of Naspers – or as much as R1.85 trillion.

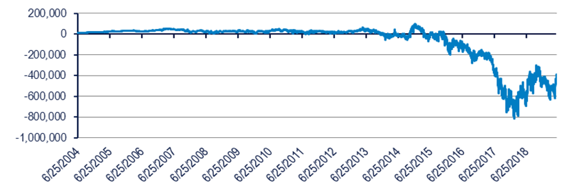

This value gap emerged only in 2015, with the appointment (coincidentally?) of Bob van Dijk as CEO. The value gap has been as much as R800 billion since then and is now close to its post-2015 low. Its further direction will be of crucial importance to shareholders and, one hopes, also the senior managers of Naspers who control its destiny through the high voting shares they own.

Figure 1: Naspers – NAV minus market value (R billion)

The NAV and market value of Naspers have much in common. Common to both is the market value of the listed assets it owns (Tencent and MailRu being the most important). Also common is the value accorded to the unlisted assets of Naspers, though the value ascribed to these unlisted assets by the directors and included in the balance sheet may well be greater than the value accorded them by the market.

This could be one reason why NAV exceeds market value. What will not be recorded in the Naspers balance sheet or in NAV, but will affect the market value, is the expected cost of running the Naspers head office, as assumed by investors and potential investors. The more shareholders are expected to pay management for their services in the future – including the extra shares to be issued to managers that will dilute their share of the company – the less Naspers shares will be worth today.

A further force that can add to or subtract from the value of a company is the expected value to its shareholders of the business that the company is expected to undertake in the future. The more profitable the investment programme of a company is expected to be, the more value a company will offer its shareholders. Profit in the true economic senses means the difference between the internal rate of return on shareholder capital invested by the firm and its opportunity cost, that is, the returns its shareholders could expect from similarly risky investments made with its capital when invested outside the company. It is the economic, not the accounting profit earned after allowing for the cost of utilising equity as well as debt capital, that matters for the market value.

This cost of their capital for SA shareholders – or the required return on the capital they have entrusted to Naspers – is of the order of 14% a year. This 14% is equivalent to the returns currently available to wealth owners in the RSA bond market (about 9% a year for a 10-year bond) plus a premium, to compensate for the risks that these returns may not be met from the averagely risky SA company.

If Naspers were expected to achieve consistent returns of more than 14% on the large capital investments it makes every year, this programme could be expected to add to its market value. If the market expected otherwise, where the returns on the investments would fall short of their costs, then the investment programme would be expected to destroy the wealth of shareholders. And the more Naspers was expected to invest, the more value destruction would be reflected in its share price: that is, the larger the difference between NAV and market value would become.

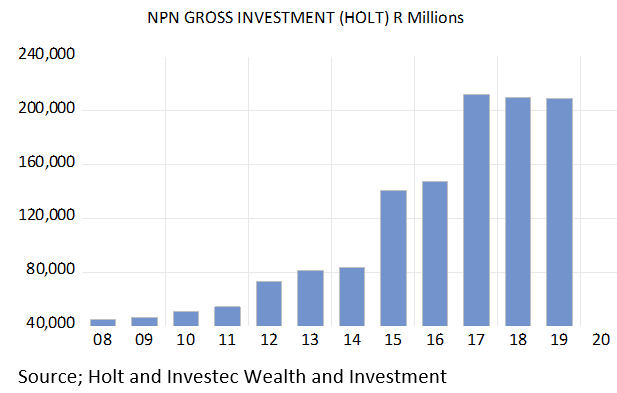

We draw on the Credit-Suisse-Holt database for estimates of the recent investment activity of Naspers. The sums invested are large in absolute terms as may be seen in figure 2 below: they’re estimated as of the order of R200bn per annum in recent years. Holt also estimates a currently negative return on capital invested by Naspers – that is, a negative cash flow return on investment (CFROI). If the estimate of the scale of the Naspers is correct, then the investment programme is large enough to account for a large reduction in its market value accorded by a sceptical share market.

The recent sale by Naspers of 2% of its Tencent holding realised nearly US$10 billion. A large additional war chest it must be agreed, but not perhaps enough to result in as much value destruction of the order recently observed.

It suggests that shareholders also attach significant costs to them of the rewards expected to be awarded to managers – perhaps particularly in the form of share issues and options – that over time can consistently dilute their share of the company. If the number of shares issued as remuneration amounts every year to as much as 1% of the shares in issue, this becomes an expensive exercise for shareholders.

Figure 2: Naspers – gross investment

Source: Holt and Investec Wealth & Investment

Will the future be much different for Naspers shareholders?

The critical issue for shareholders in the restructured Naspers remains as before. How successful – how economic value adding or destroying – will its investment programme become, and how generous will the company be to its managers?

There seems little likelihood of much change in behaviour of either kind that would cause investors to change their assumptions about Naspers. The managers are unlikely to become less ambitious in their search for game-changing investments of the kind it made in Tencent. But it will soon be doing so out of two highly interlocked companies.

The international investment activities will presumably be conducted out of Amsterdam. The South African company will also have an investment programme of its own, presumably in South African and African opportunities. One imagines, however, that the larger investments bets will be made internationally by the Amsterdam-listed company, given the much larger opportunity set. Dividends (largely from Tencent) that flow out of Amsterdam back to South Africa will presumably be influenced by the scale of this investment programme.

One anticipates that both companies will not easily convince investors that they are capable of undertaking enough value-adding investments to compensate for the cost of management. Therefore, the Naspers shares will be priced lower (to compensate for value destruction and head office costs) for an expected return in line with market averages. Given a lower than otherwise share price for both companies, both are likely to stand at a discount to NAV and should continue to offer a value gap of significance.

Yet the Amsterdam company will also be priced to offer a market-related return for a company listed in Amsterdam and, under the jurisdiction of the Netherlands, a developed economy. The owners of the 27% free float in the new Amsterdam company will accordingly attach a lower real discount rate to the expected benefits of their share of the company. They will be satisfied with lower expected nominal and real returns, because they will attach less risk to doing business with the government of the Netherlands than with the SA government.

The lower returns required of a company in the Netherlands will be equivalent to the yield on a Netherlands government bond (close to zero, even negative) plus the same 5% risk premium. This makes for a required nominal return of 5% rather than the 14% required of a South African-listed company, where inflation is expected to be much higher and the sovereign risk premium is higher.

The important difference in real expected returns (returns adjusted for expected inflation) is an expected average real 5% in the Netherlands (given no expected inflation, only a risk premium) and a real return in South Africa of about 3% higher (8% real return expected from the average South African company). This 8% real is the equivalent of the 14% nominal required return, less the 6% inflation rate expected in South Africa.

This lower real discount rate makes Naspers shares worth more in Amsterdam than they would be worth in South Africa (all else remaining unchanged) and also worth more for shareholders in Naspers South Africa with their Amsterdam investment.

But all else will not remain the same, including the market value of Tencent shares. This will still be the main force driving the value of the Naspers companies. What could change the game for shareholders – and help further lower the gap between NAV and market value – would be for the company to reward its managers on their ability to close this value gap. That surely would align the interest of managers and shareholders and therefore add value.