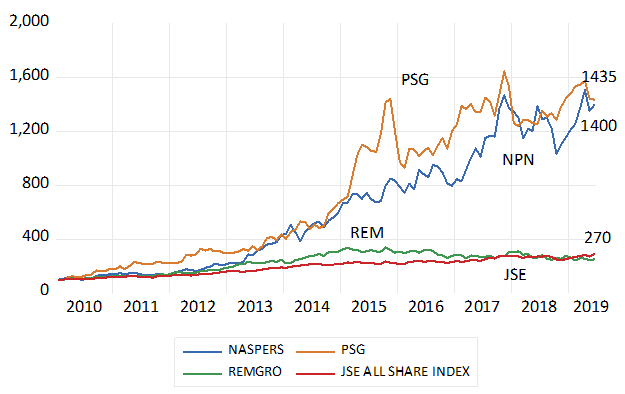

Investment holding companies have long played a large role on the JSE. Two of the more important of them, Naspers and PSG, have provided spectacular returns for their shareholders in recent years. R100 invested in PSG in January 2010 with dividends reinvested in the stock has grown to R1435 by late June 2019. The same R100 invested in Naspers would have almost as well for its shareholders over the same period having increased its rand value by 14 times.

Not all holding companies are equal. A one-time darling of the JSE, Remgro has barely managed to keep pace with the JSE All Share index- R100 invested in Remgro or the JSE in 2010 would have grown to about the same R250.

Total returns; Naspers, PSG, Remgro and the JSE All Share Index (2010=100)

Source; Bloomberg, Investec Wealth and Investment

The advantage enjoyed by the managers of an investment holding company is that the capital made available to them is permanent capital. It cannot be cashed in, as is the case with a mutual fund or unit trust, that may be obliged to redeem capital and may have to sell down their assets to do so.

It therefore can invest in potentially market return beating companies, companies that will return more than their opportunity costs of capital – if only in time. Its often significant shareholdings may give it a useful, active role in improving the performance of the operating companies it invests in.

While shareholders in a listed investment holding company cannot force any liquidation of assets, they can always sell their shares. At a price that would have to be attractively low enough to promise the buyer a return at least as good as is promised elsewhere in the market place – for a similar degree of risk.

This market-clearing price, multiplied by the number of shares issued will determine the market value of the holding company. And this market value, as in the case of Naspers (since 2014) and Remgro (continuously since 2010 )– has been well blow their Net Asset Value (NAV). That is the holding company is likely to be worth than the sum of its parts – were the parts unbundled to its shareholders. No doubt to the chagrin of its managers when their company is judged to be worth more- sometimes much more – dead than alive. And who may well have delivered market beating returns in the past.

The market and net asset value of the holding company will always have much in common. The market value of its listed assets and its net debt would be included in both- as would the value of its unlisted assets- though the market may judge them to be worth less than the director’s estimates included in NAV.

The market value will however be influenced by two other important forces, not reflected in its marked to market, balance sheet, its NAV. Included in market value, but not NAV, will be two unknowns -the expected implicit costs to shareholders of running the head office- and the present value of its ongoing investment programme. Past performance may not be a good guide to expected performance as we are often reminded. The economic value expected to be added by the extra capital to be invested by the holding company may be presumed by the market place, to be insufficiently promising to compensate for the costs of running the head office. Hence reducing market value relative to NAV

The way for the managers of a holding company to close the value gap between NAV and Market Value is clear. That is to adopt a highly disciplined approach to acquisitions and investments. And be as disciplined in the rewards offered managers. A plan to list major unlisted assets to prove their value and to unbundle them when their investment case has been proved, will help add market value. Market value adding – performance related pay – can also be well aligned with the interest of shareholders if made dependent on closing this gap between NAV and market value.