While issuing debt is more dangerous than issuing equity it receives more encouragement from shareholders and the regulators [1]. Clearly debt has more upside potential. If a borrower can return more than the costs of funding the debt- return on equity improves- and there is less to be shared with fellow shareholders. But clearly the upside comes with extra risks that shareholders will bear should the transactions funded with debt turn out poorly. Any increase in the risks of default will reduce the value of the equity in the firm – perhaps very significantly so.

The accounting model of the firm regards equity finance as incurring no charge against earnings. Hence you might think would help the argument for raising permanent equity capital rather than temporary debt capital. But this is clearly not the case with the rules and regulations and laws that govern the capital structure of companies. It is also represented in the attitude of shareholders to the issuing of additional equity. They have come to grant ever less discretion to the company boards and their managers to issue equity. Less so with risky debt.

Perhaps the implicit value of the debt shield – taxes saved expensing interest payments – without regard to the increase in default risk- confuses the issues for investors and regulators. It is better practice to separate the investment and financing decisions to be made by a firm. First establish that an investment can be expected to beat its cost of capital,-. Cost of capital being the required risk adjusted return on capital invested whatever itsthe source including investing the cash generated by the company itself. Somethingof capital, including internally generated cash that could be given back to shareholders for want of profitable opportunities. When this condition is satisfied the best (risk adjusted) method of funding the investment can be given attention.

The apparent aversion to issuing equity capital to fund potentially profitable capes or acquisitions seems therefore illogical. Or maybe it represents risk loving rather than risk averse behaviour. Debt provides potentially more upside for established shareholders and especially managers who may benefit most from incentives linked to the upside.

Raising additional equity capital from external sources to supplement internal sources of equity capital is what the true growth companies are able to do. And true growth companies do not pay cash dividends, they reinvest them earning Economic Value Added (EVA) for their shareholders. A smaller share of a larger cake is clearly worth more to all shareholders

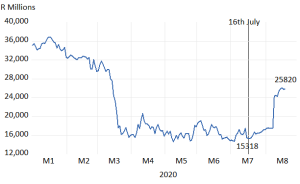

There are two recent JSE cases worth notice. TFG shareholders approved the subscription of an extra R3.95b of capital on July 16th to add about 20% to the number of shares in issue. The company on August 19th was worth R25.8b or R10.5b more than its market value of the 16th July. Or worth some R6.5b more than the extra capital raised. The higher share price therefore has already more than compensated for the additional shares in issue. ( see below)

The Foschini Group (TFG) Market Value R millions (Daily Data to August 19th 2020)

Source; Bloomberg, Investec Wealth and Investment

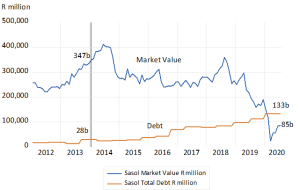

The other example is Sasol (SOL) now with a market value of about R80 billion so heavily depressed by about R110b of outstanding debt. The extra debt was mostly incurred funding the Lake Charles refinery that ran so far over its planned cost and called for extra debt. SOL was worth over R400b in early 2014 with debts then of a mere R28b. The market value of SOL (R86b) now less than the value of its debts, is clearly being supported by the prospect of asset sales and a potential capital raise. The company would surely be much stronger had the original investment in Lake Charles been covered more fully by additional equity capital. Capital they might have been able to raise with much less dilution. It might also have prevented the new management team from having to sell off what might yet prove to be valuable family silver that they intend to do. That is assets capable of earning a return above their cost of capital. If so a very large rights issue could still be justified to bring down the debt to a manageable level and as with TFG increase the value of its shares by more (proportionately) than the number of extra shares issued. (see chart below)

Source; Bloomberg, Investec Wealth and Investment

[1] Paul Theodosiou until recently non-executive chairman of JSE listed Reit Self Storage (SSS) and previously MD of now de-listed Acucap (ACP) of which I was the non-executive chairman repoded to my enquiry about the differential treatment of debt and equity capital raising as follows

Typically at the AGM a company will seek two approvals in respect of shares – a general approval to issue shares for cash (which these days is very limited – 5% of shares in issue is the norm) and an approval to place unissued shares under the control of directors (to be utilized for specific transactions that will require shareholder approval). These need 75% approval. So shareholders keep a fairly tight rein on the issue of shares.

Taking on or issuing debt, on the other hand, leaves management with far more discretion. Debt instruments can be listed in the JSE without shareholder approval, and bank debt can be taken on at managements discretion. The checks and balances are more broad and general when it comes to debt. Firstly, the MOI will normally have a limit of some kind (for Reits, the loan to value ratio limits the amount of debt relative to the value of the assets). If the company is nominally within its self-imposed limits, shareholders have no say. Secondly, the JSE rules provide for transactions to be categorised, and above a certain size relative to market cap, shareholders must be given the right to approve by way of a circular issued and a meeting called. The circular will spell out how much debt and equity will be used to finance the transaction, and here the shareholders will have discretion to vote for or against the deal. If they don’t approve of the company taking on debt, they can vote at this stage. Thirdly, shareholders can reward or punish management for the way they manage the company’s capital structure – but this is a weak control that involves engaging with management in the first instance to try and persuade, and disinvesting if there isn’t a satisfactory response.