The case for a company buying back its own shares is clear enough. If the shareholders can expect to earn more from the cash they could receive for their shares than the company can expect to earn re-investing the cash on their behalf, the excess cash is best paid away.

Growing companies have very good use for the free cash flows they generate from profitable operations. That is to invest the cash in additional projects undertaken by the company that can be expected by managers to return more than the true cost of the cash. This cost, the opportunity cost of this cash, is the return to be expected by shareholders when investing in other companies. Such expected returns, a compound of share price gains and cash returned, are often described as the cost of capital. And firms can hope to add wealth for their shareholders when the internal rate of return realized by the company from its investment decisions exceeds the required returns of shareholders.

All firms, the great and not so good, will be valued to provide an expected market competing rate of return for their shareholders. Those companies expected to become even more profitable become more expensive and the share prices of the also rans decline to provide comparable returns. How then can a buyback programme add to the share market value of a company? Perhaps all other considerations remaining the same- including the state of the share market, the share price should improve in proportion to the reduced number of shares in issue. But far more important could be the signaling effect of the buy backs. Giving cash back to shareholders, especially when it comes as a surprise, will indicate that the managers of the company are more likely to take their capital allocating responsibilities to shareholders seriously.

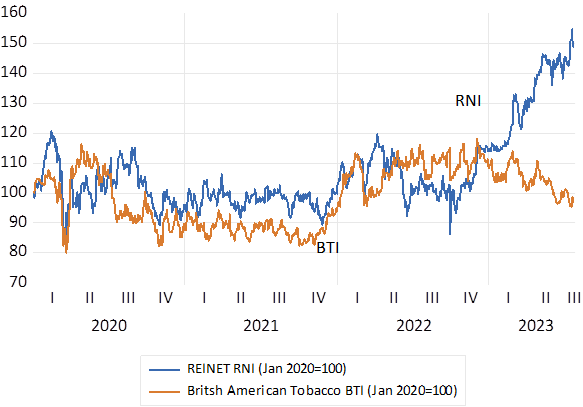

The case of Reinet (RNI) the investment holding company closely controlled by Mr. Johann Rupert is apposite. Mr. Rupert believes the significant value of the shares bought back by Reinet have been “cheap” because they cost less than their book value or net asset value (NAV) Yet the market value of Reinet still stands at a discount to the value of its different parts and may continue to do so. Firstly, shareholders will discount the share price for the considerable fees and costs levied on them by management. Secondly, they may believe the unlisted assets of Reinet may be generously valued in the books of RNI, so further reducing the sum of parts valuation suggested by the company and reducing the value gap between true adjusted NAV and the market value of the holding company. Finally, the market price of RNI has been reduced because the returns realized by the investment programme of RNI may not be expected to beat their cost of capital and will remain a drag on profits and return on capital. Therefore the value of the holding company shares is written down – to provide market competing, cost of capital equaling, expected returns- at lower initial share prices. And realizing a difference between the NAV reported by the holding company (its sum of parts) and the market value of the company – share price multiplied by the number of shares in issue (net of the shares bought back)

Yet for all that, the shares bought back may prove to be cheap should Reinet further surprise the market with further improvements in its ability to allocate capital. And the gap between NAV and MV could narrow further because the value of its listed assets decline. Indeed, shareholders should be particularly grateful for the recent performance of RNI when compared to the value of its holding in British American Tobacco (BTI) its largest listed investment. RNI has outperformed BTI by 50% this year. Unbundling its BTI shares – an act normally very helpful in adding value for shareholders because it eliminates a holding company discount attached to such assets- would have done shareholders in RNI no favours at all this year.

Fig.1; Reinet (RNI) Vs British American Tobacco (BTI) Daily Data (January 2020=100)

Source; Iress and Investec Wealth and Investment

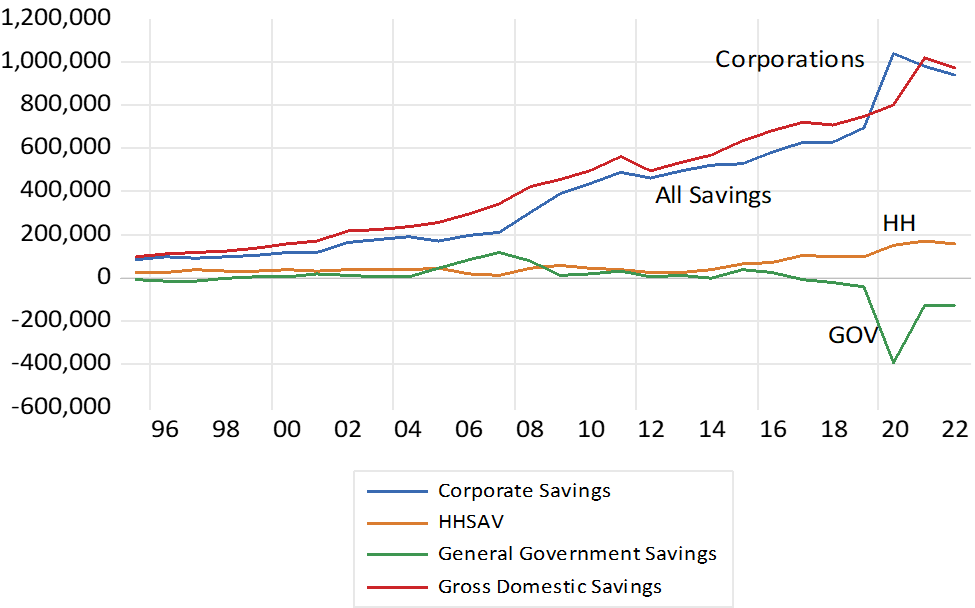

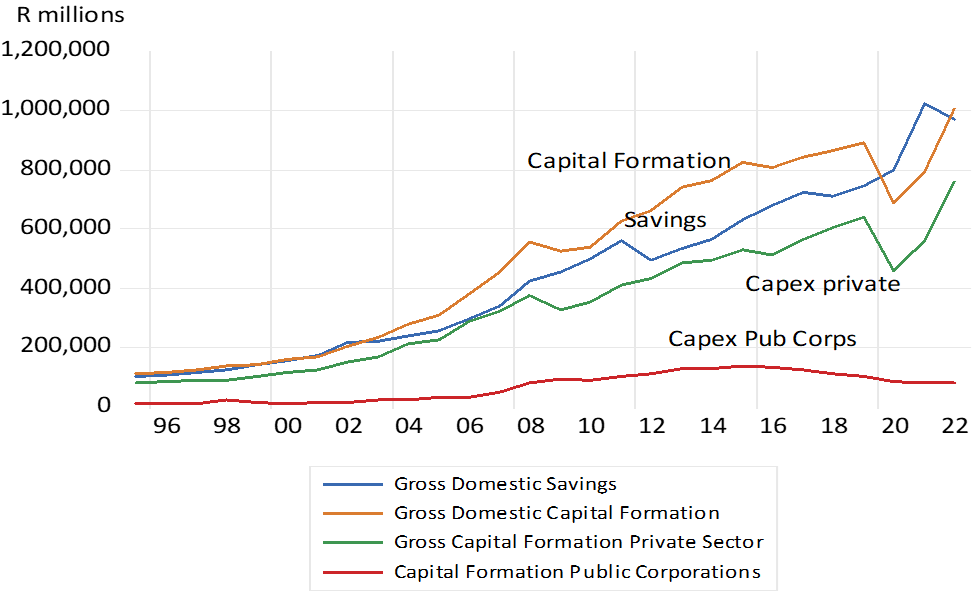

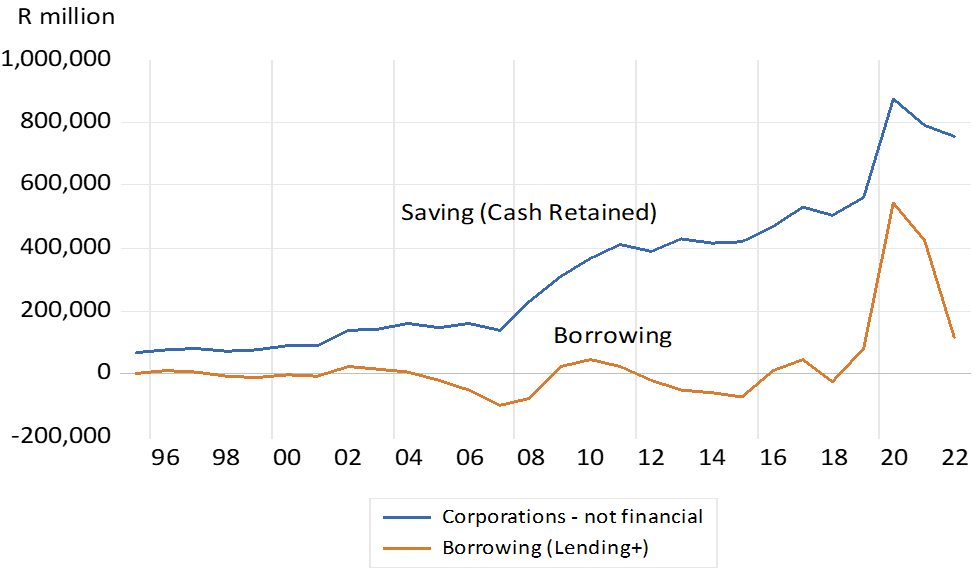

The recent trends in flows of capital out of and into businesses operating in SA are shown below. It may be seen that almost all the gross savings of South Africans consist of cash retained by the corporate sector, including the publicly owned corporations. (see figure 2) Though their operating surpluses and retained cash have been in sharp recent decline for want of operational capabilities and revenues rising more slowly than rapidly increasing operational costs. Their capital expenditure programmes have suffered accordingly as may be seen in figure 3. The savings of the household sector consist mostly of contributions to pension and retirement funds and the repayment of mortgages out of after-tax incomes. But these savings are mostly offset by the additional borrowings of households to fund homes, cars, and other durable consumer goods. The general government sector has become a significant dissaver with government consumption expenditure exceeding revenues plus government spending on the infrastructure. It may be noticed that the non-financial corporations in South Africa have not only undertaken less capital expenditure with the cash at their disposal- they have also become large net lenders- rather than marginal borrowers- in recent years. (see figure 5)

Fig.2; South Africa; Gross Savings Annual Data (R millions)

Source; South African Reserve Bank and Investec Wealth and Investment

Fig.3; South Africa; Gross Savings and the Composition of Capital Expenditure by Private and Publicly Owned Corporations

Source; South African Reserve Bank and Investec Wealth and Investment

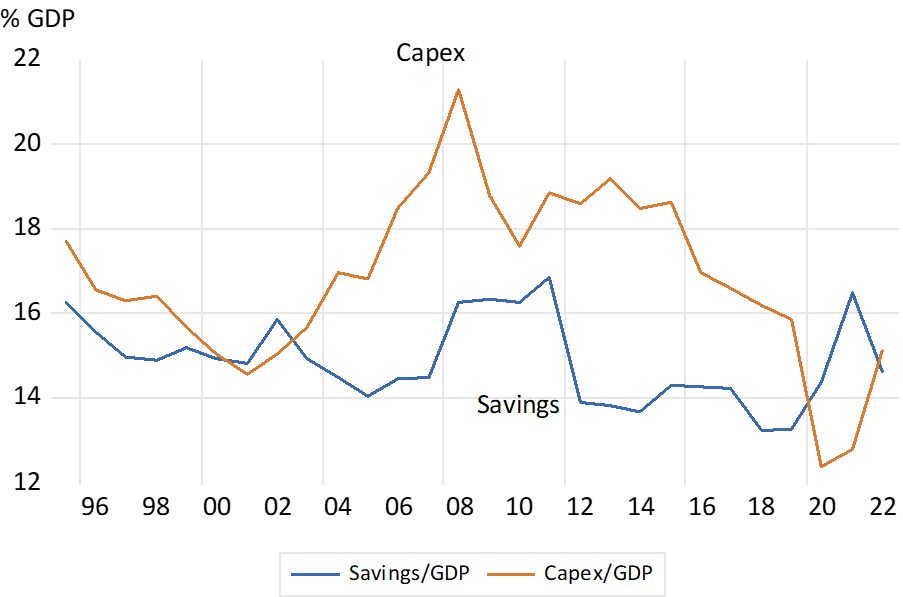

In recent years, during and post the Covid lock downs, total gross saving has come to exceed capital; formation providing for a net outflow of capital from South Africa. Rather a lender than a borrower might be the Shakespearean recipe, but the problem is that both gross savings and capex in South Africa commands a comparably small share of GDP as shown below. South Africans save too little it may be said for want of income to do so. But they invest too little in plant and equipment and the infrastructure that would promote the growth in incomes, consumption and savings. The source of capital exported is that the gross savings rate held up while the ratio of capex to GDP fell away significantly.

Fig.4; South Africa, Gross Savings and Capital Formation – Ratio to GDP – Annual Data, Current Prices

Source; South African Reserve Bank and Investec Wealth and Investment

Fig. 5; South African Non-Financial Corporations; Cash from Operations Retained and Net Lending (+) or Borrowing(-) Annual Data

Source; South African Reserve Bank and Investec Wealth and Investment

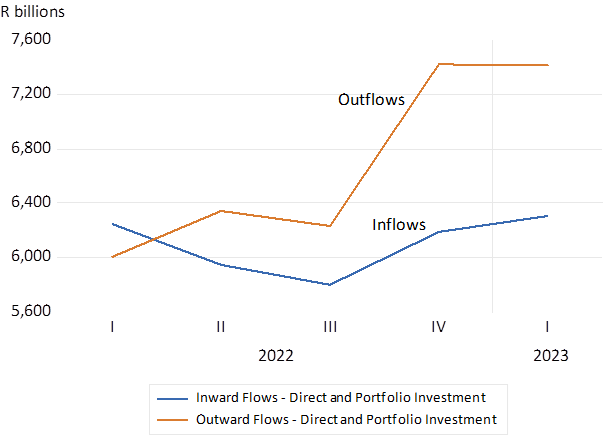

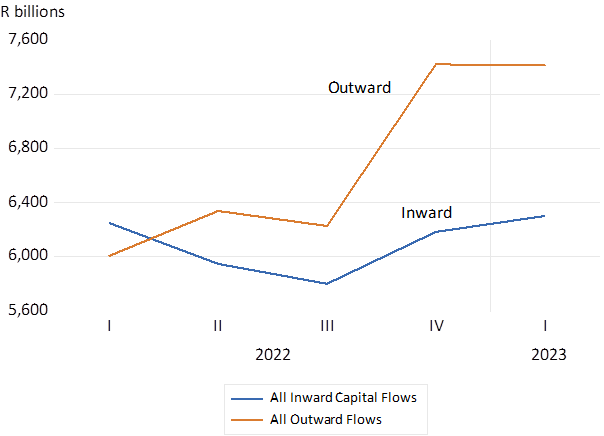

The reason many SA companies are buying back shares on an increasing scale is the general lack of opportunities they have had to invest locally with the cash at their disposal. And the cash received has been invested offshore rather than onshore on an increasing scale. For want of growth in the demand for their goods and services for all the obvious reasons. As a result the aggregate of the value of South African assets held abroad at march 2023 exceeded those of the foreign liabilities of South Africans, at current market valuations, by R1,699 billion. Total foreign assets were valued at approximately 9.5 trillion rand.

Fig 6; South Africa; Inflows and Outflows of Capital; Direct and Portfolio Investment. Quarterly Flows 2022.1 – 2023.1[i]

Source; South African Reserve Bank and Investec Wealth and Investment

Fig.7; All Capital Flows to and from South Africa; Quarterly Data (2022.1 2023.1)

Source; South African Reserve Bank and Investec Wealth and Investment

The reluctance to invest in SA makes realizing faster growth ever more difficult. That the cash released to pension funds and their like is increasingly being invested in the growth companies of the world, rather than in SA business, is the burden of a poorly performing economy that South Africans have to bear. Rather a borrower than a lender be- if the funds raised can be invested in a long runway of cost of capital beating projects. Faster growth in the economy would lead the inflows of capital and restrain the outflows of capital required to fund a significant increase in the ratio of capital expenditure to GDP and a highly desirable excess of capex over gross savings.

[i] The investments are defined as direct when the flows are undertaken by shareholders with more than 10% of the company undertaking the transactions. And as portfolio flows when the shareholder has less than 10%. Much of the economic activities of directly owned foreign companies in South Africa, including their cash retained and dividends paid to head office will be regarded as direct investment. For example, describing the activities of a foreign owned Nestle or Daimler Benz in SA.