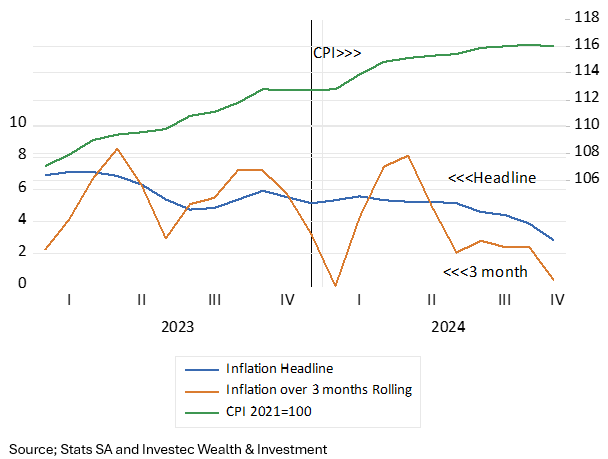

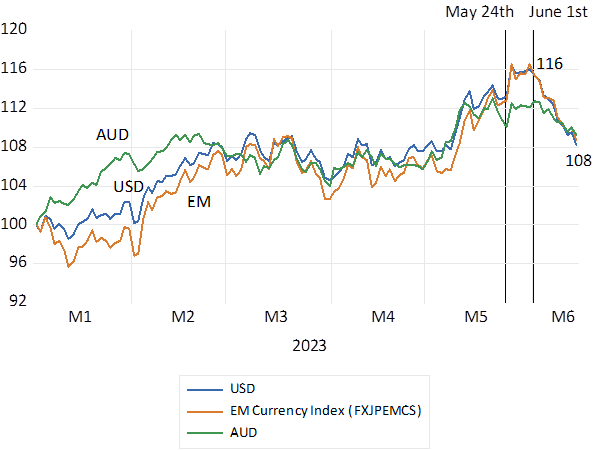

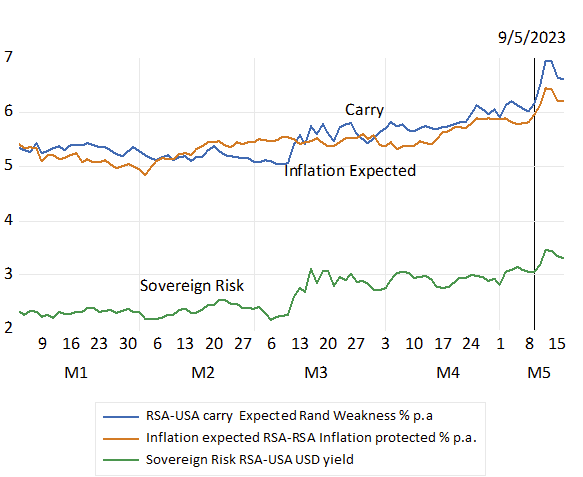

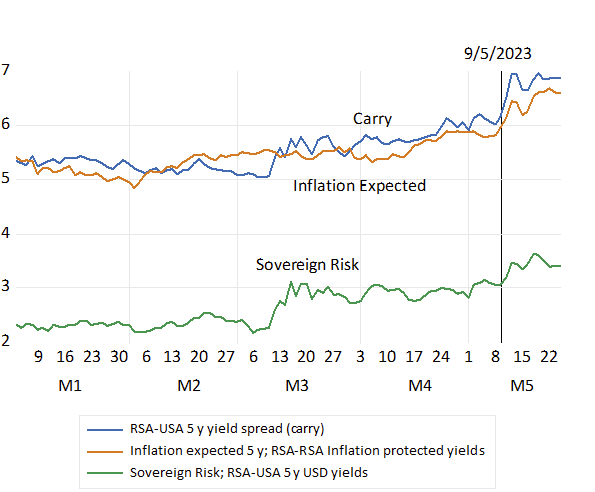

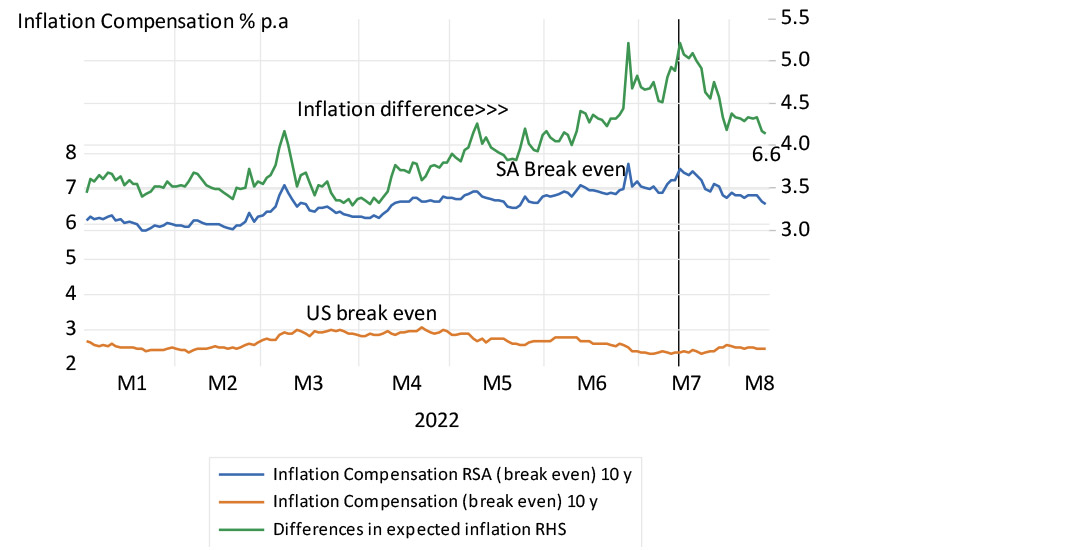

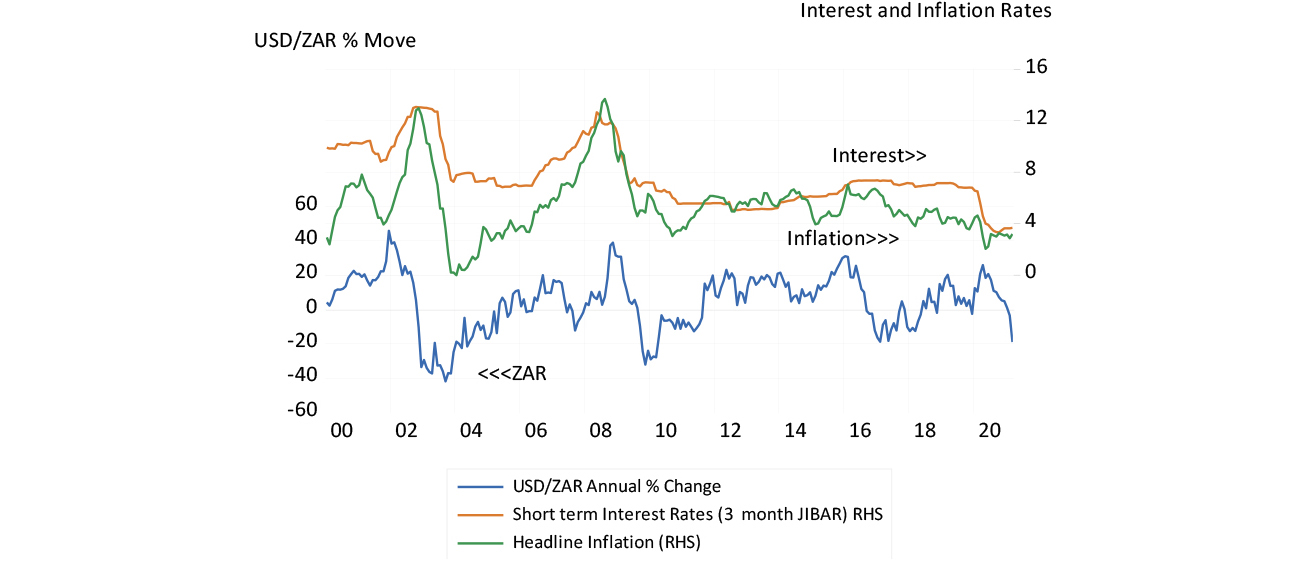

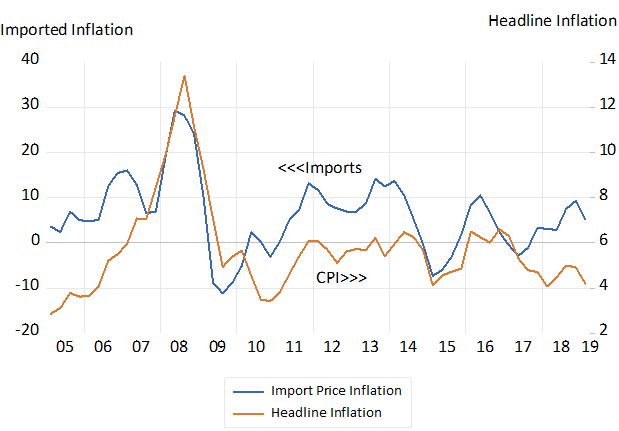

The rand has enjoyed a strong recovery in recent weeks. We say enjoyed advisedly. A strong rand is very helpful to households and their spending. It means less inflation (even deflation of the prices of goods or services with high import content or of those that compete with imports) and so less inflation expected in the prices firms set for their customers. If rand strength or even rand stability can be maintained, lower interest rates will follow to further encourage spending. Households directly account for over 60% of all spending, while spending by firms that supply households on capital equipment and their wage bills will take their cue from household demands. Any hope of a cyclical recovery of the SA economy depends crucially on the now more helpful direction of the rand.

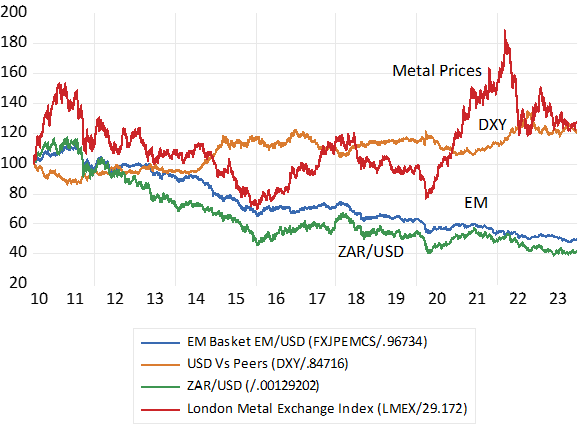

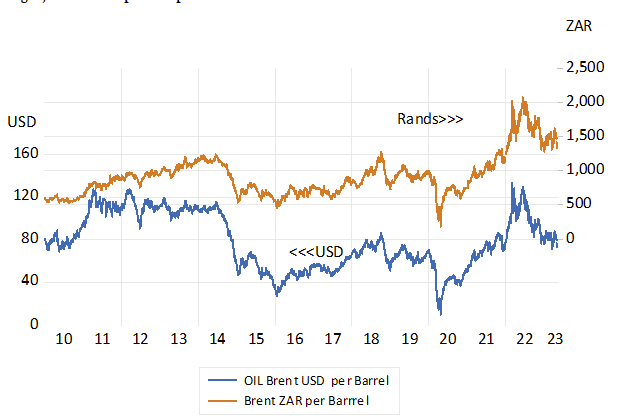

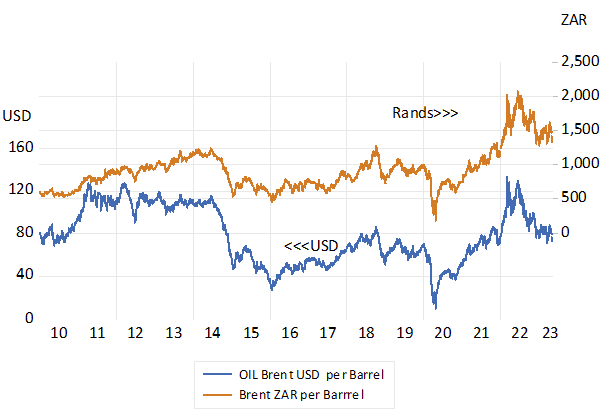

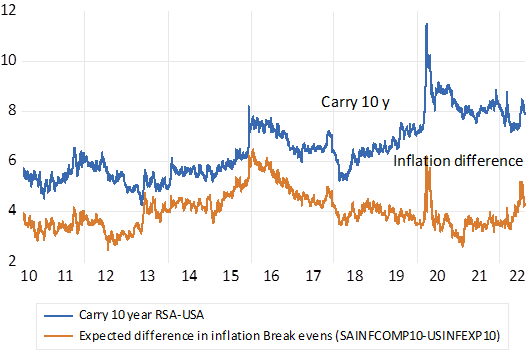

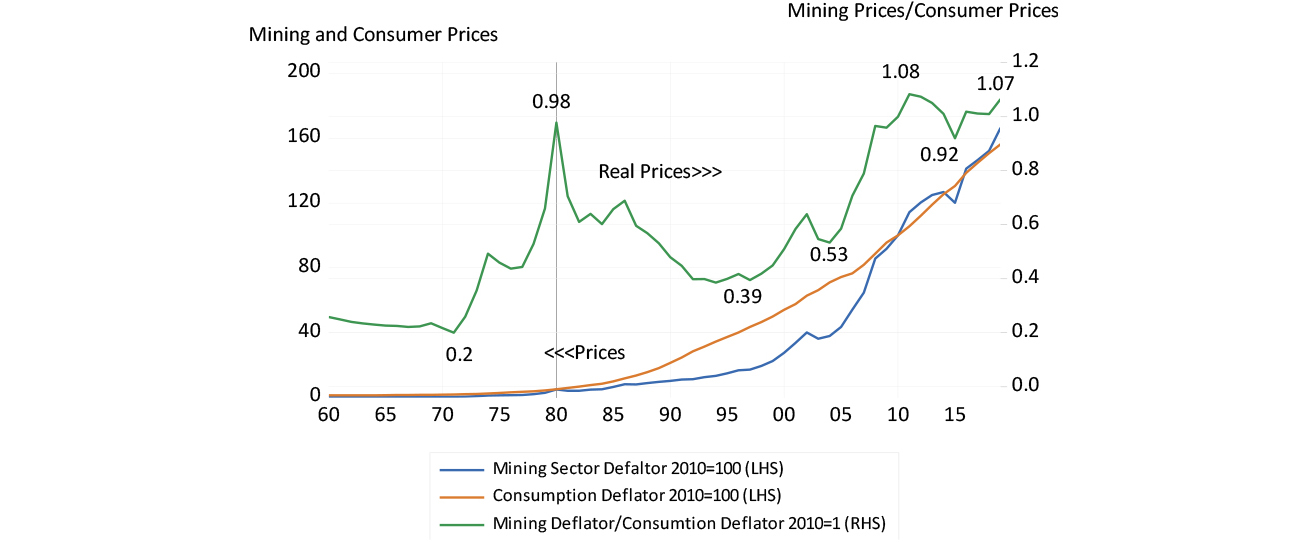

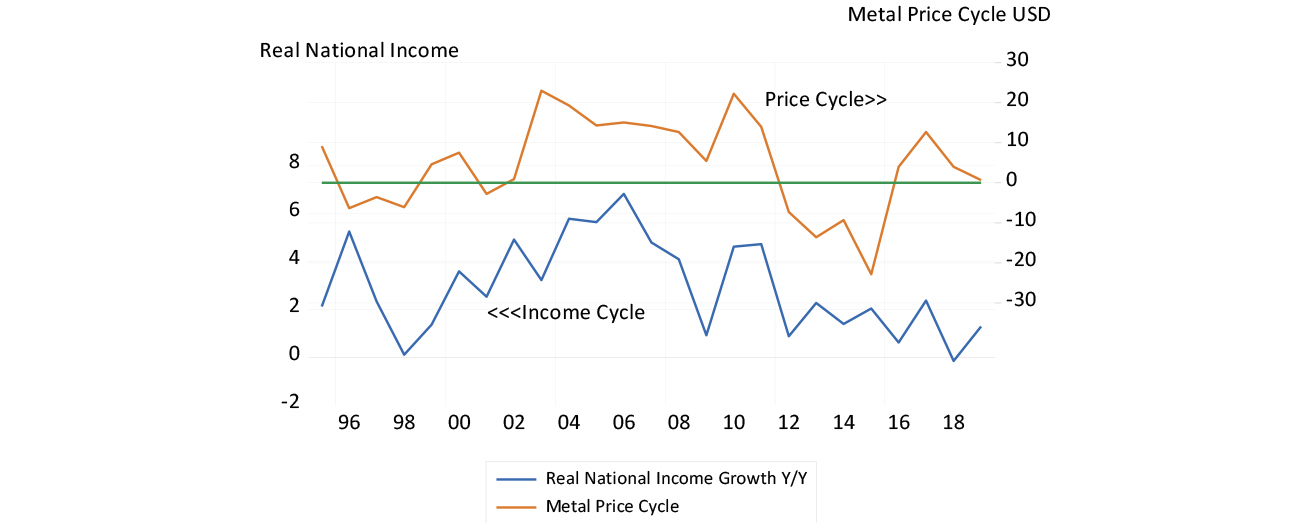

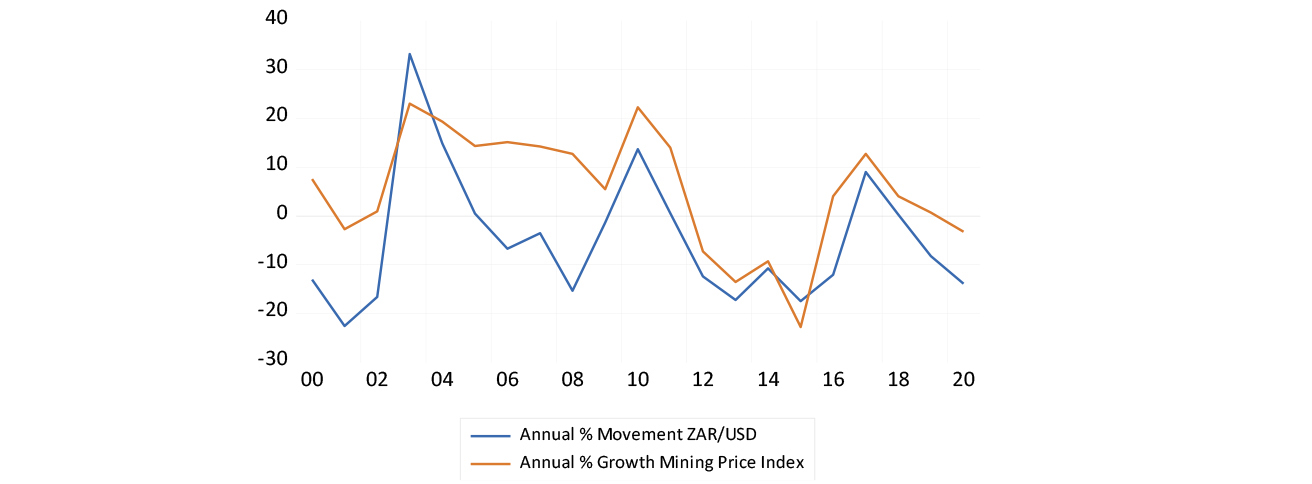

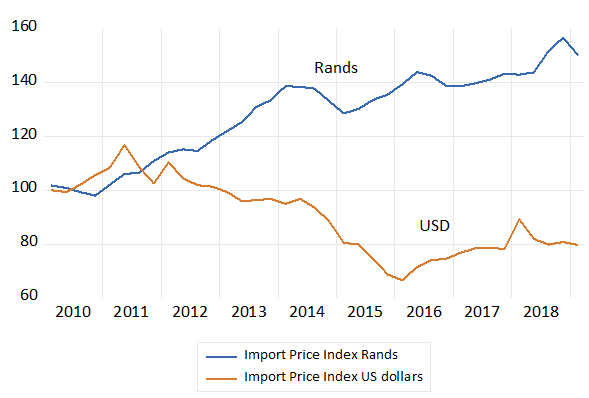

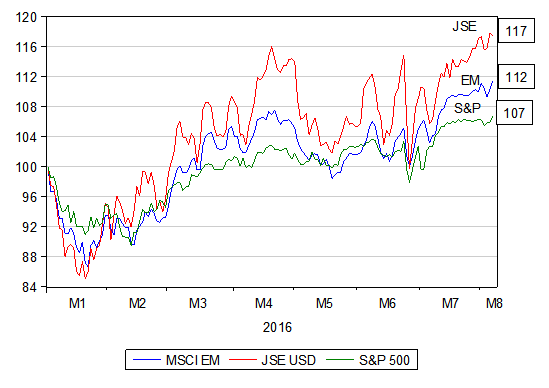

Exporters may see their profit margins contract with a stronger rand. However, crucial for them will be the reasons for rand strength or weakness as the case may be. If the rand appreciates because the global economy is gathering momentum, or is expected to do so, then rand strength may well be accompanied by higher US dollar prices for the metals and minerals they sell on world markets, and vice versa, rand weakness might well be accompanied by or even caused by lower commodity prices. In which case revenues gained via a depreciated rand may well be offset by weaker US dollar prices. As has been the case for much of the past few years. Falling dollar prices for metals and minerals for much of the past few years – other than gold- have accompanied the weaker rand. And to some extent can be held responsible for the weaker rand.

Fig 1; Commodity Price Index (CRB) in USD and in ZAR

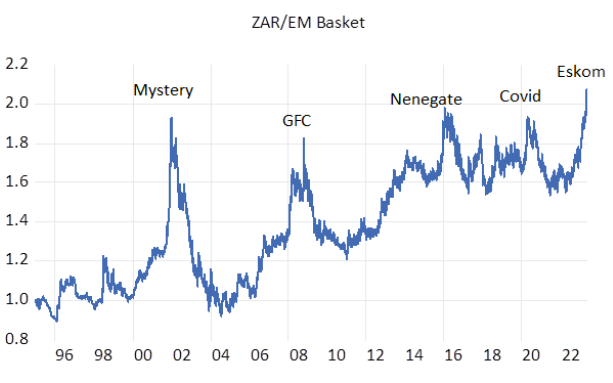

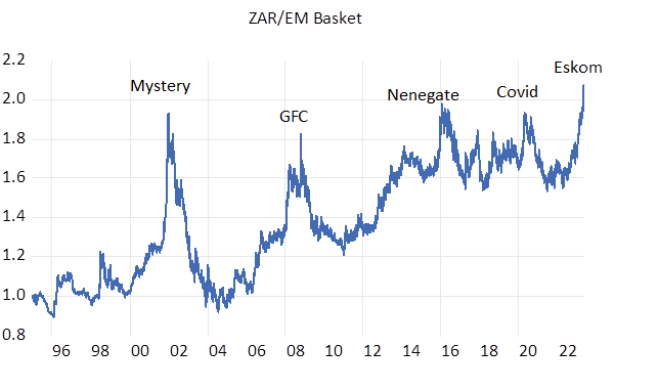

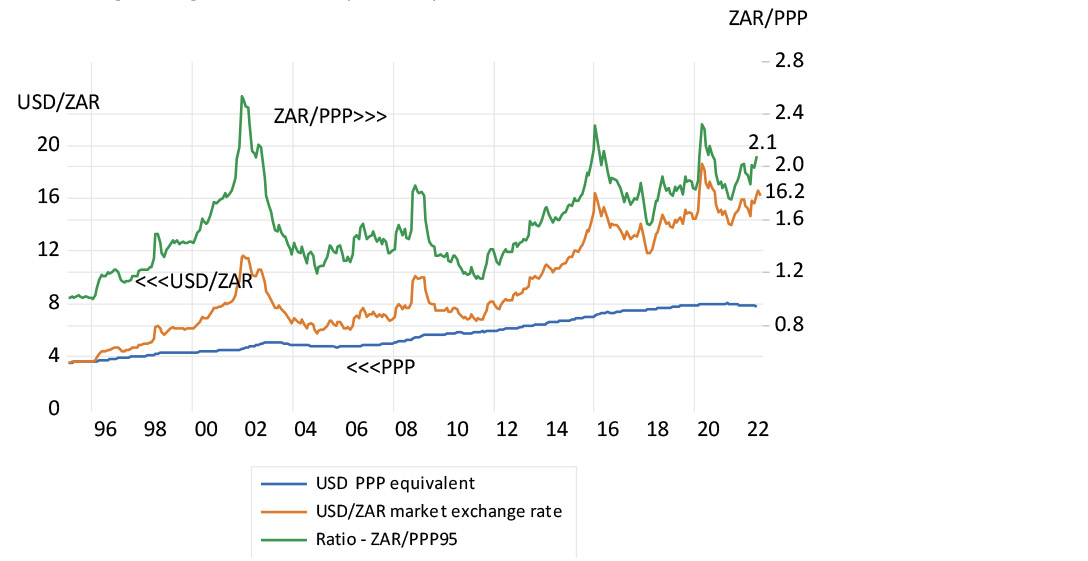

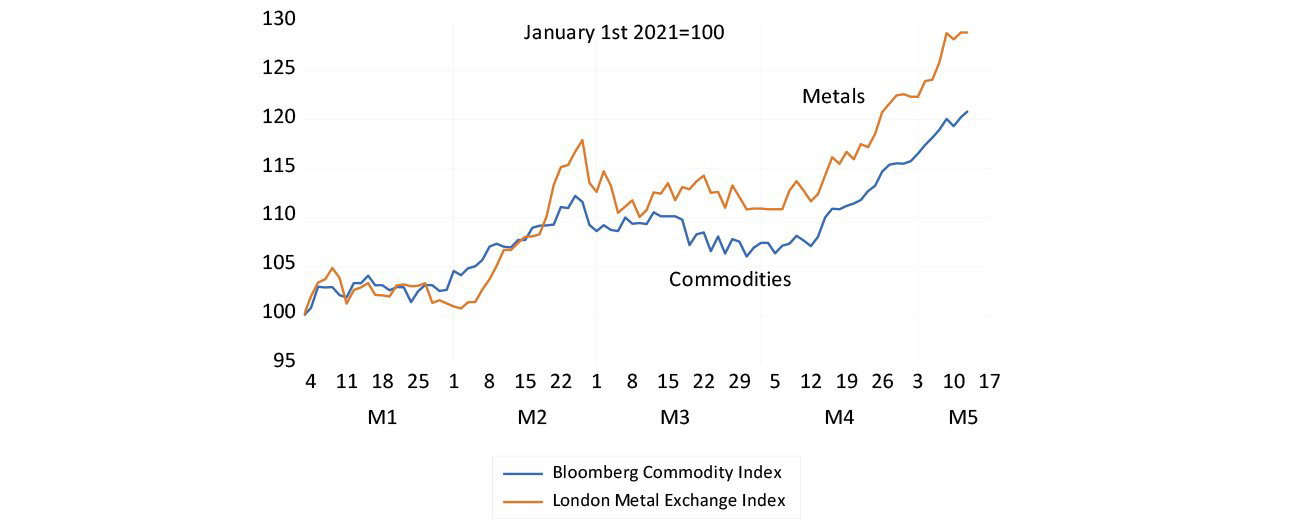

It is therefore important to identify the sources of rand weakness or strength. It is important to recognise the difference between global forces and SA-specific events that have driven or can drive the rand weaker or stronger, even though the implications for the state of the SA economy of rand strength or weakness, from whatever cause, global or SA specific, will be similar. The more risky (uncertain) the outlook for the global and SA economies, the weaker the rand and vice versa whatever the sources of more or less risk- be they Global or South African.

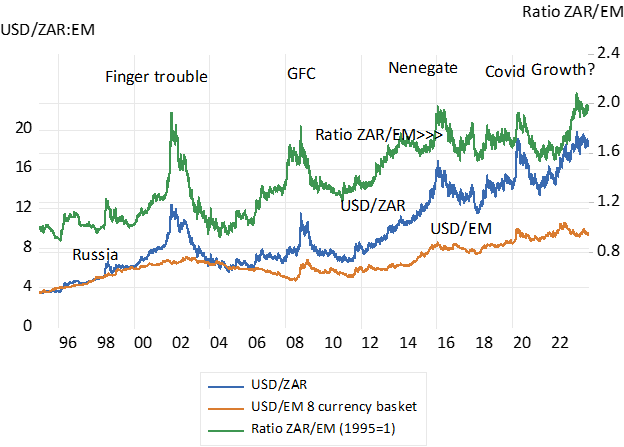

However if the cause of rand weakness is SA in origin – attributable to economic policies or expectations of them – those responsible for currency weakness and a consequently weaker economy can be held accountable by the democratic process. Policy makers may lose support, enough to change the direction of policy direction that could add rand strength. The rand strength that has accompanied the local government elections and a politically damaged Presidency are pointing in this direction and have made disruptive interference in SA’s fiscal policy settings less likely. Hence an extra degree of ZAR strength for SA specific reasons.

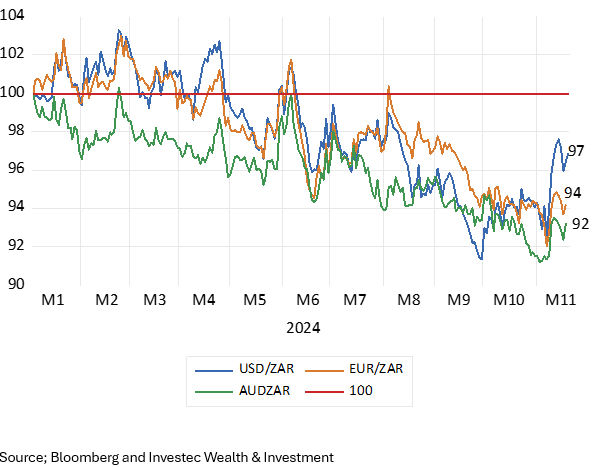

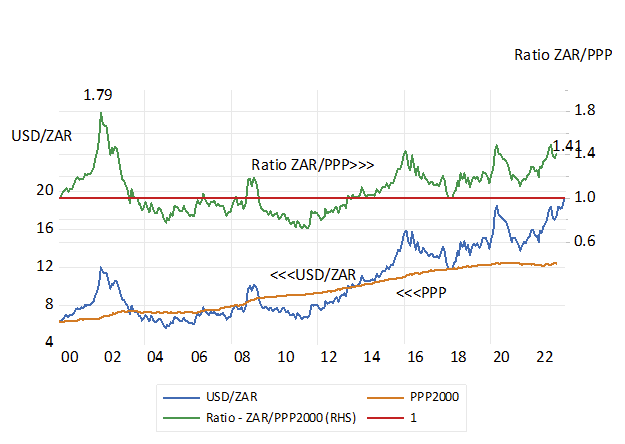

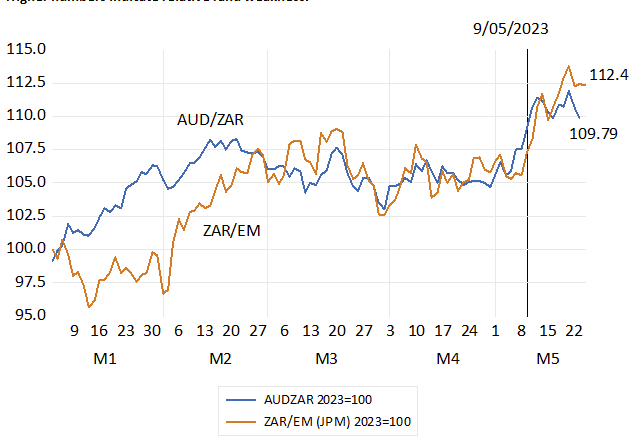

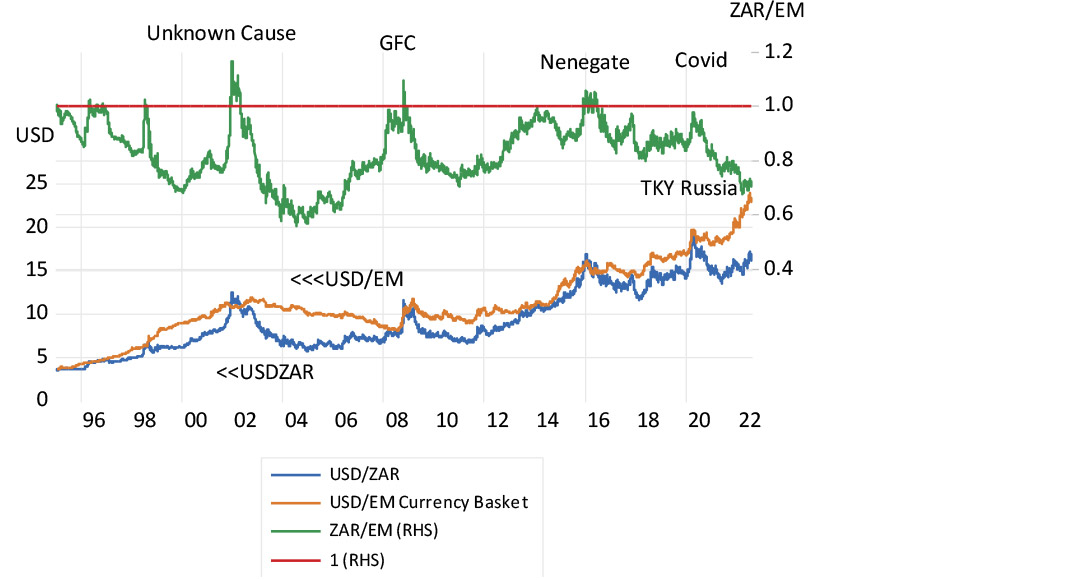

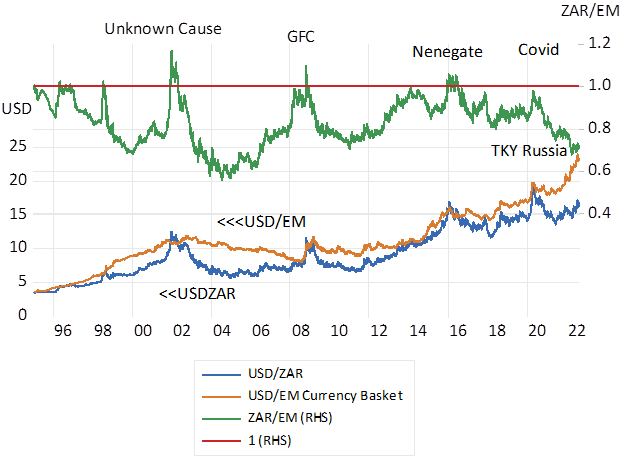

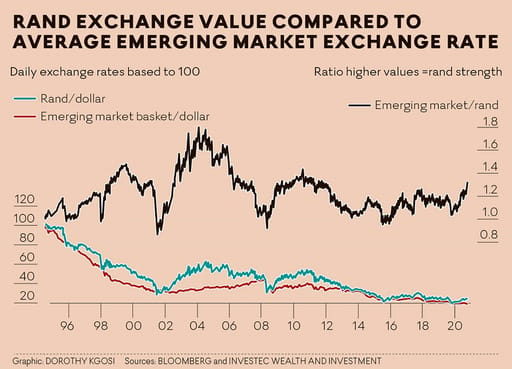

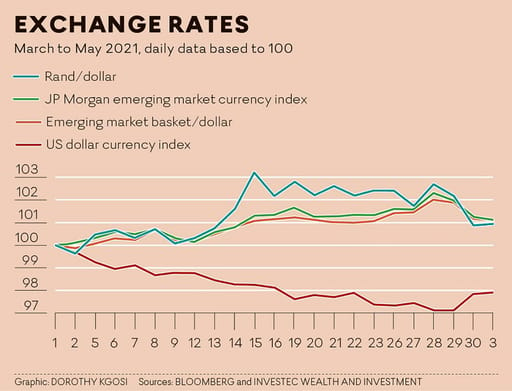

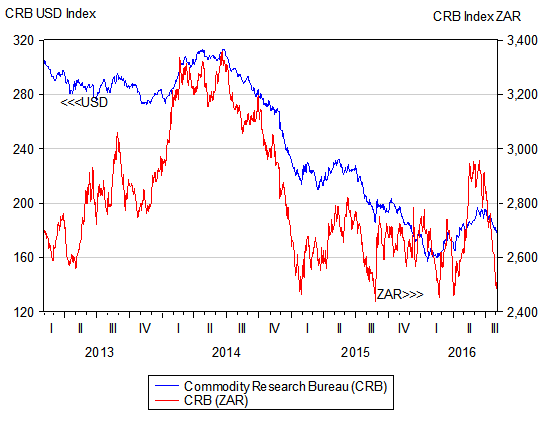

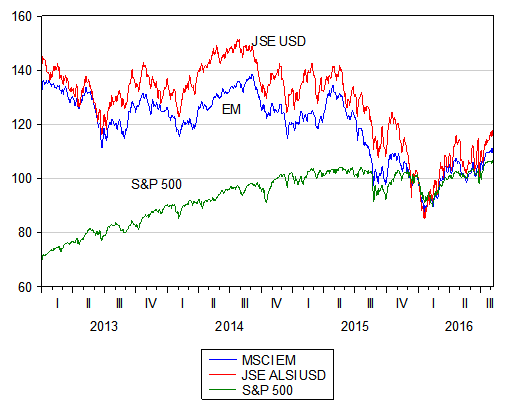

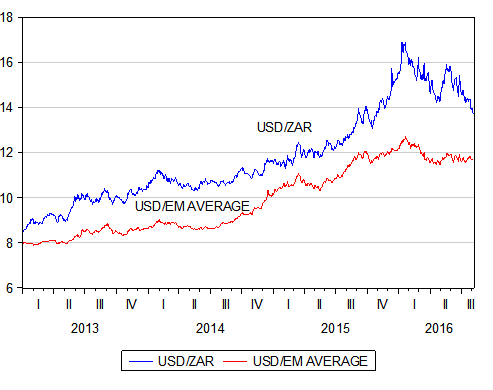

We offer an analysis that clearly can identify the causes of rand weakness or strength as either global or SA specific. The simple method is to compare the behaviour of the USD/ZAR exchange rate with that of nine other emerging market (EM) currencies that can be expected to be similarly influenced as is the ZAR by global forces. We compare an Index of these USD/EM exchange rates with that of the USD/ZAR exchange rate below (The exchange rates included in the Index are all given the same weight. The Index is made up of the Turkish Lira, Russian Ruble, Hungarian Forint, Brazilian Real, the Mexican, Chilean, Philippine Pesos, Indian Rupee and the Malaysian Ringgit). It may be seen that the weakness of the rand since 2013 has been accompanied by EM currency weakness generally. Much of the rand depreciation of recent years may therefore be attributed to global not SA specific influences on capital flows and exchange rates. It has been an extended period of dollar strength as much as EM weakness. The US dollar has also gathered strength vs the euro and the yen over this period.

Fig.2; The USD/ZAR and the USD/EM Average, 2013-2016 (Daily Data)

Source; Bloomberg and Investec Wealth and Investment

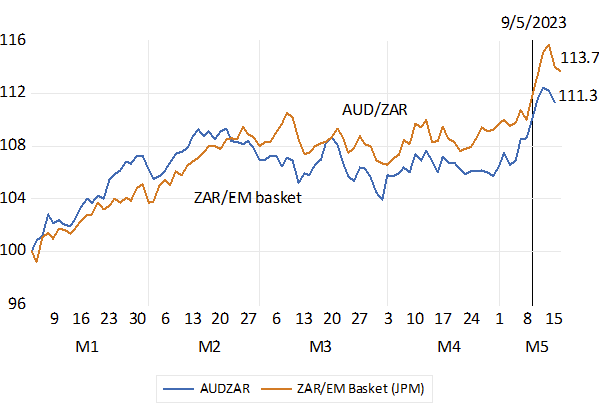

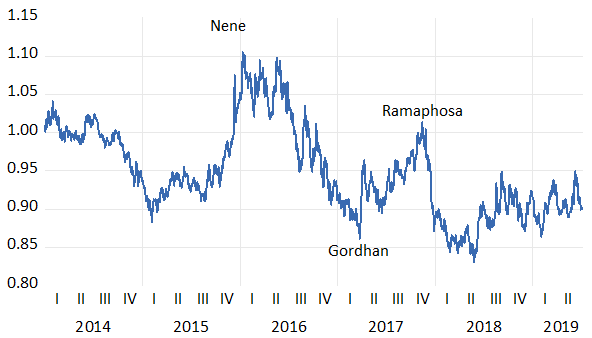

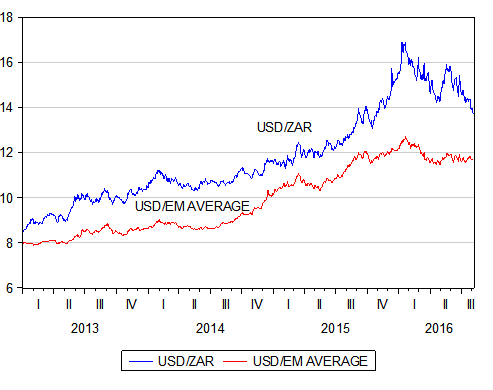

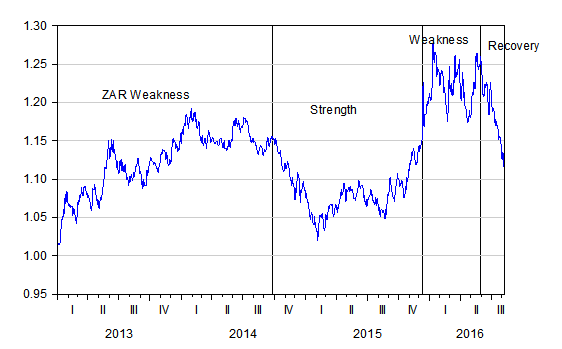

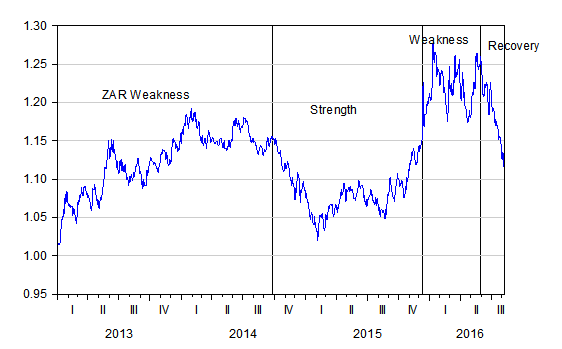

However it has not been only a matter of USD strength. As may be seen below when we compare the performance of the ZAR to the EM basket there have been periods of rand weakness – from January 2013 to September 2014- followed by a period of relative rand strength that turned into significant weakness in late 2015 when president Zuma frightened the market for the rand and RSA’s with his surprise sacking of the then Minister of Finance Nene. As may also be seen the recovery of the rand dates from late May 2016 and has gained significant momentum recently with the outcomes, expected and realized in the Local Government elections of August 3rd 2016. Since the close of trade on Friday 5th August the ZAR has gained 2.6% vs the USD while the nine currency EM average exchange rate is about 0.90% stronger vs the USD.

Fig.3; Performance of the USD/ZAR Vs the USD EM average. (Daily Data; January 2013=1)

Source; Bloomberg and Investec Wealth and Investment

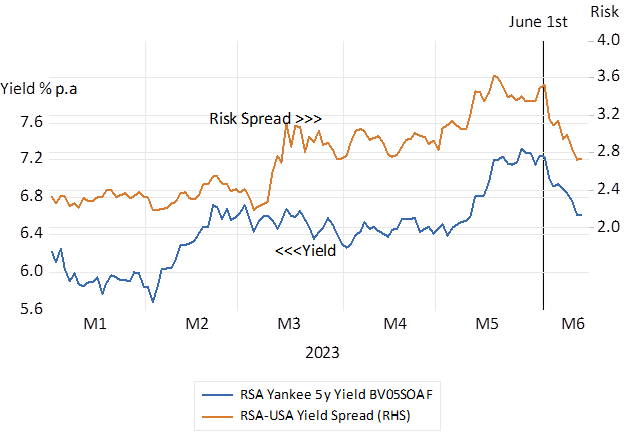

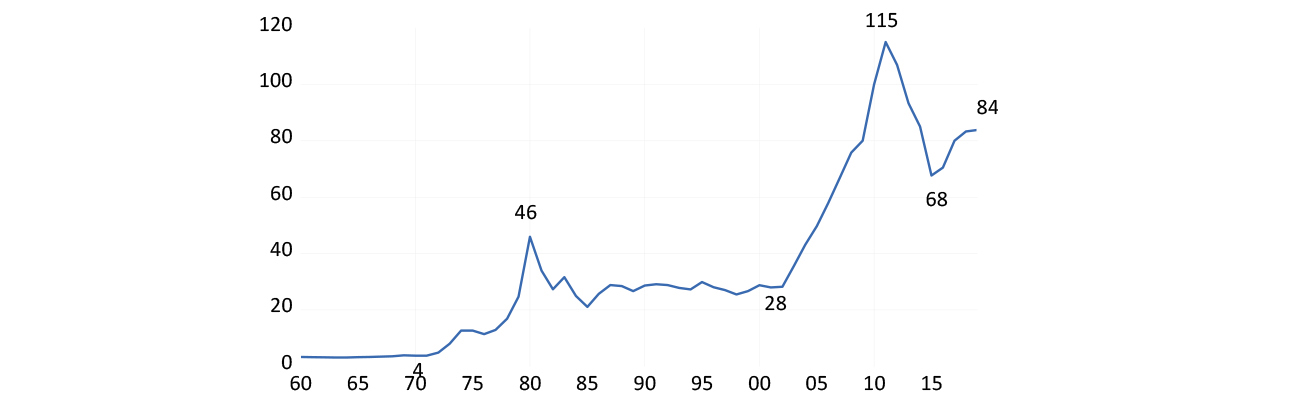

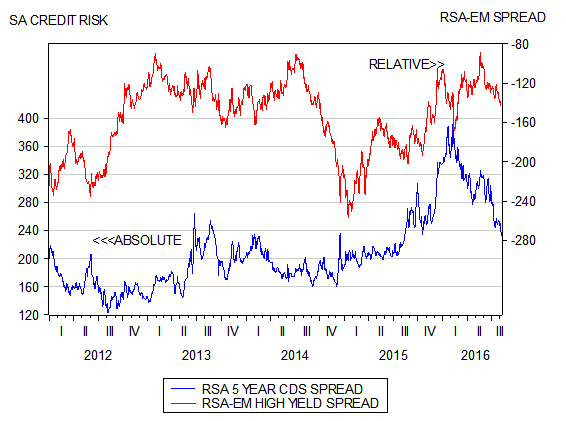

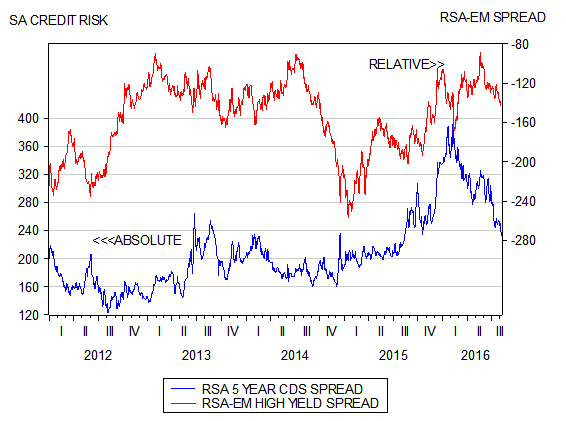

A similar picture emerges when we trace the Credit Default Swaps for RSA dollar denominated debt and high yield EM debt in Fig 4. The CDS spread is equivalent to the difference in the USD yield on an RSA or EM 5 year bond and that of a five year US Treasury Bond. The credit rating of RSA debt in a relative sense can be expressed as the difference between the cost of insuring RSA debt against default Vs the cost of insuring high yield EM debt. The larger the negative spread in favour of RSA’s, the more favourable SA’s credit rating compared to other EM borrowers. As may be seen the RSA rating deteriorated in 2015 and is now enjoying something of an improved rating. Though the credit spreads indicate that there is some way to go before RSA credit attained the relative and absolute standing it had in 2012.

Fig.4; SA and Emerging Market Credit Spreads.

Source; Bloomberg and Investec Wealth and Investment

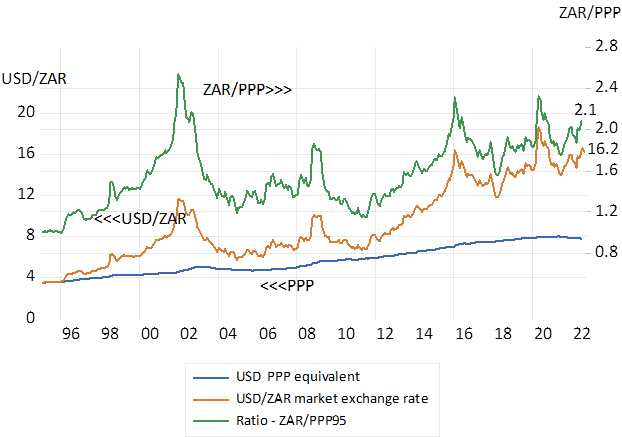

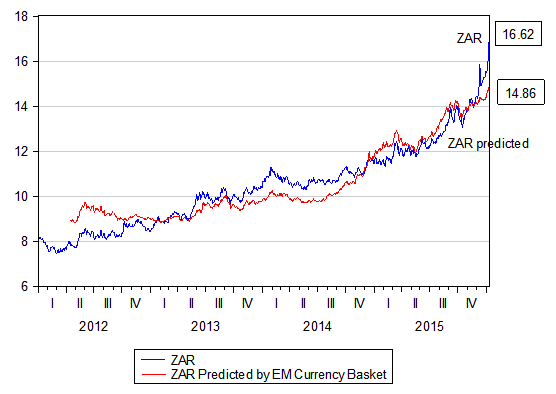

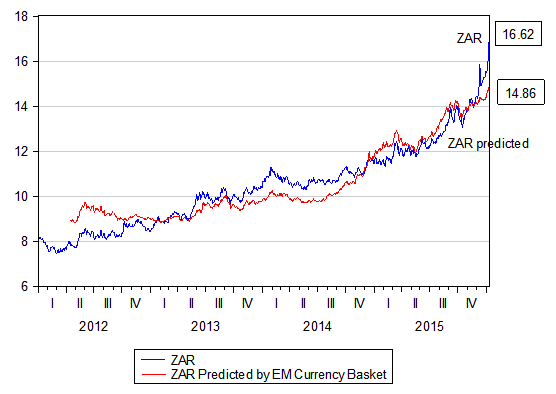

To take the analysis further we have run a regression equation that explains the USD/ZAR exchange using the USD/EM exchange rate as the single explanatory variable. The fit is a statistically good one as may be seen in figures 5 and 6. The EM currency basket explains over 90% of the USD/ZAR daily rate on average over the three and a half years. But as may be seen in figure 4, the ZAR was significantly undervalued in late 2015. The predicted value of the USD/ZAR at 2015 year end, given the exchange value of the other EM currencies might have been R14.86 compared to actual exchange rate at that fraught time of R16.62. Or in other words SA specific risks had made the USD almost R2 more expensive than it might have been at the end of 2015.

Fig.5; Value of ZAR compared to EM Basket on 1/1/2016.

Source; Bloomberg and Investec Wealth and Investment

As we show in figure 5 this valuation gap had disappeared by August 5th 2016. The USD/ZAR exchange rate is now almost exactly where it could have been predicted to be by global forces alone. That is to say the current exchange value of the ZAR is precisely in line with other EM exchange rates.

Fig.6; Value of ZAR compared to EM Basket on 8/8/2016 Daily Data (2013-2016 August)

Source; Bloomberg and Investec Wealth and Investment

The future of the ZAR will, as always, be determined by the mix of global and SA specific forces. At current exchange rates it may be concluded that there is no margin of safety in the exchange value accorded the ZAR. It will gain or lose value from this level with changes in SA risk or with the direction of global capital flows that determine the value of EM currencies, bonds and equities.

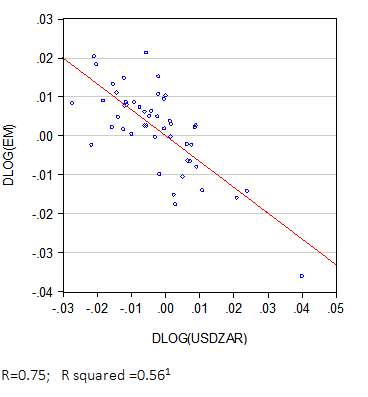

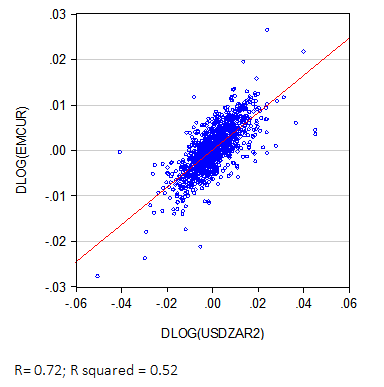

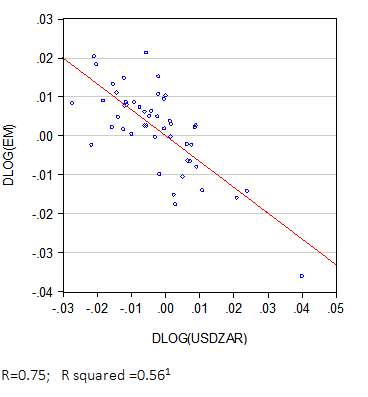

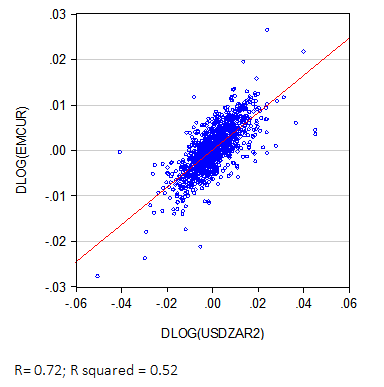

The global capital flows acting on the ZAR are well represented by the direction of the EM equity markets. The ZAR and other EM exchange rates will continue to take their cue from flows into and out of EM equity and bond markets. In figures 7 and 8 below we show how sensitive has been the relationship between daily moves in the ZAR and by implication other EM exchange rates, to daily moves in the value of EM equities – represented by the benchmark MSCI EM Index. We show a scatter plot of these daily percentage changes below. This relationship has been particularly close recently as may be seen in the figures below.

Fig 7. Daily % Moves in the MSCI EM Equity Index and the USD/ZAR, June 1st 2016- August 8th 2016

R=0.75; R squared =0.56[1]

Source; Bloomberg and Investec Wealth and Investment

Fig 8: Daily % Moves in the EM Currency Index and the USD/ZAR; January 1st 2013 – August 8th,2016

R= 0.72; R squared = 0.52

Source; Bloomberg and Investec Wealth and Investment

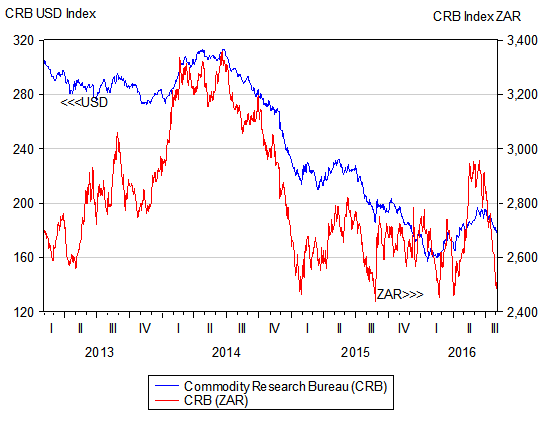

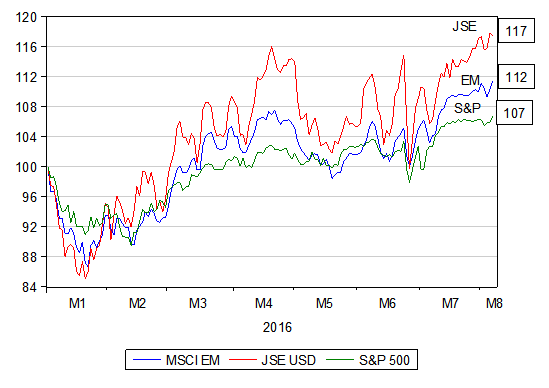

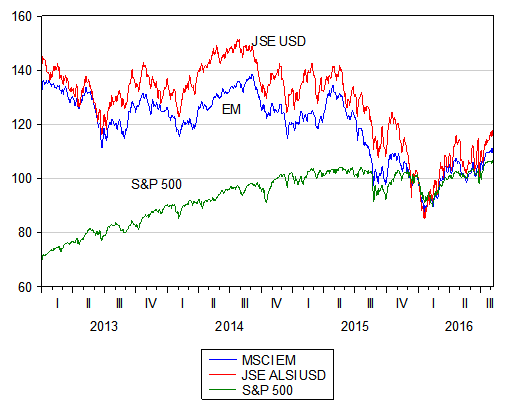

A further feature of global equity markets this year has been the highly correlated movements in the S&P Index and EM Indexes including the JSE- when valued in USD. (See figure 9 below) Also notable is the extent to which the JSE, when valued in USD has outperformed other EM equities as well as the S&P tis. This has come after years of EM and JSE underperformance of a similar scale- especially when measured in strong USD.

Fig.9; Equity Market Trends; USD. Daily Data 2016 (January 2016=100)

Source; Bloomberg and Investec Wealth and Investment

Fig.10; Equity Market Trends. USD. Daily Data 2013-2016 (January 2016=100)

Source; Bloomberg and Investec Wealth and Investment

These recent trends are a reflection of less rather than more global risk aversion- and so a search for value in equities rather than in the defensive qualities of global consumer facing companies paying predictable and growing dividends. For the sake of the SA economy we can only hope that such trends persist. If they do the opportunity may soon present itself to the Reserve Bank to lower interest rates. It should do so and immediately stop predicting higher interest rates to come. The Treasury moreover should resist the opportunity a rand aided lower petrol and diesel price will give it to raise fuel taxes. A much needed cyclical recovery will take less inflation and lower interest rates. The opportunity a stronger rand may give to lower interest rates and to avoid higher tax rates should not be wasted.

[1] R is the correlation co-efficient. The R squared is for a least squares equation dLog(ZAR) = c+ dLog(EM) + e