Click here for a shorter version of this article

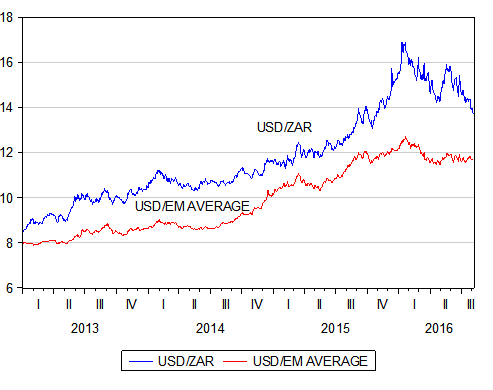

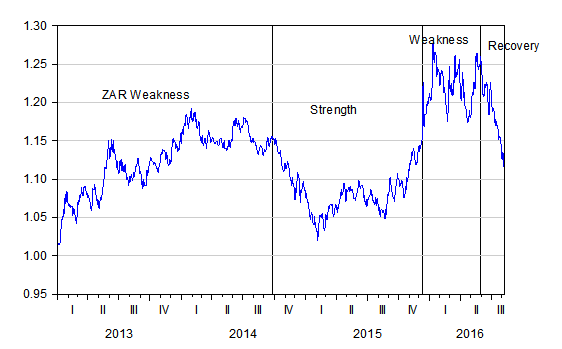

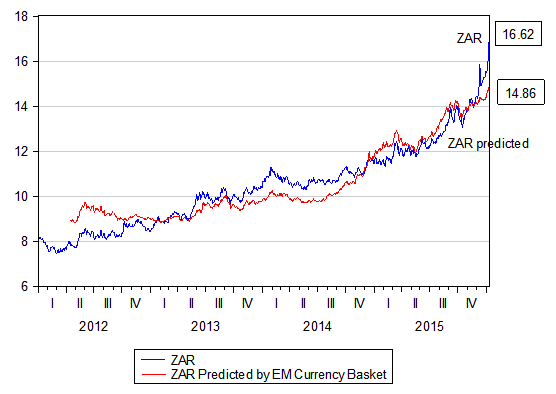

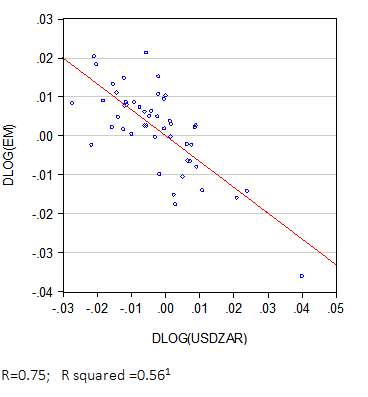

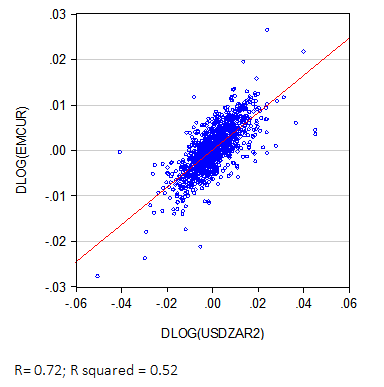

There will be good economic reasons for rejoicing should he go. The rand would strengthen – it would move back into line with its emerging currency market peers. Today this would have meant a USD/ZAR of approximately R12.6. Yesterday, April 12th a day of protest and a day when the probability of Zuma going sooner rather than later improved, saw a basket of EM currencies gain seven cents vs the weaker USD while the ZAR gained 34 cents, indicating less SA specific risk priced into the rand.

If the rand maintains these better values lower inflation will follow the lower costs of imports and the lower prices for exports and would bring lower short term interest rates in its wake. Cheaper than otherwise goods and services and credit would encourage households to spend more- as would the higher house prices and equity in homes that accompany lower mortgage rates and a more hopeful outlook for South Africa. And the firms that supplied them would be much more inclined to add, rather than contract capacity and hire more rather than fewer employees, as they are now doing. The SA business cycle would turn up rather than down.

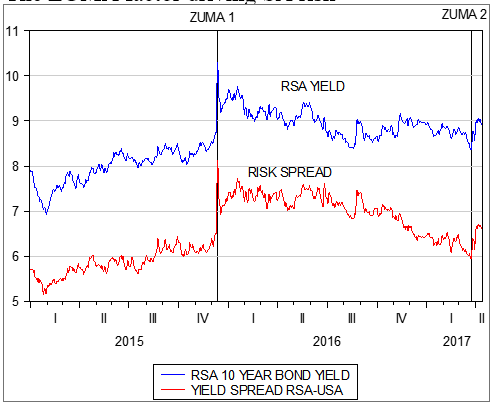

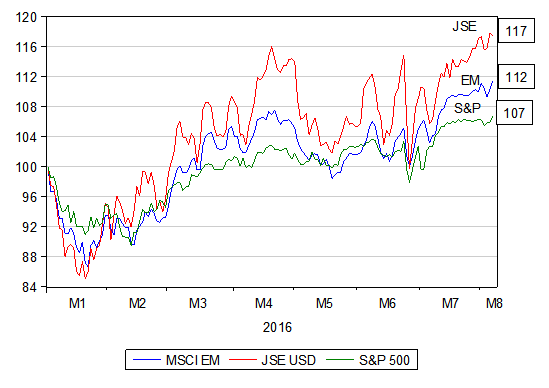

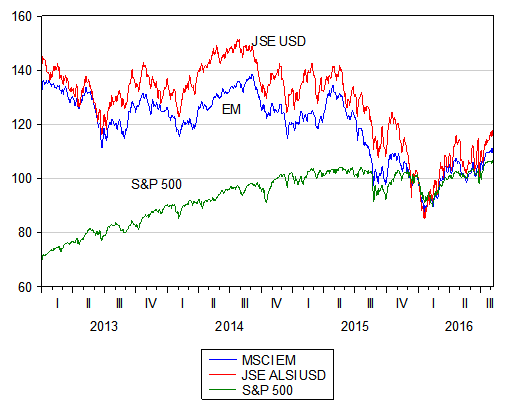

The yield on longer dated RSA debt would also tend to go back to where it was, reducing the cost of servicing our national debt –easing the burden on SA taxpayers and opening up the possibility of more help for the poor and improve the prospects of growth friendly, lower tax rates. The first Zuma attempt to control the Treasury in December 2015 took the yield on RSA 10 year bonds from 8.5% p.a in early December that year to about 9.6% by early January 2016. This move also widened the spread between RSA and US debt by about the same 100bp ( see figure below) from about 5.7% p.a to 6.7%. The latest Zuma intervention in the Treasury has seen this risk premium rise further, but not dramatically, from a still unsatisfactory 6.46% level in early 2017 to the current 6.6% p.a level.

The ZUMA factor driving SA risk

Source; I-net Investec Wealth and Investment

This spread may be regarded as the SA risk premium, the extra returns in rands, all South African investments have to be able to offer to justify their viability – in addition to their covering the additional business risks associated with a particular enterprise. This extra return is also the rate at which the rand is expected to depreciate over the next ten years. And the weaker the rand the more inflation expected. The Zuma interventions have understandably have resulted in the rand being expected to lose dollar value at a faster rate and so also, in a consistent way, to increase the expected inflation rate. The market place understandably expects a weakened Treasury to be less able to control government spending and less conservative in how such spending is funded. That is less able to raise taxes and less willing to pay ever higher rates of interest on its debts and so more inclined to print money, an approach that would be clearly inflationary.

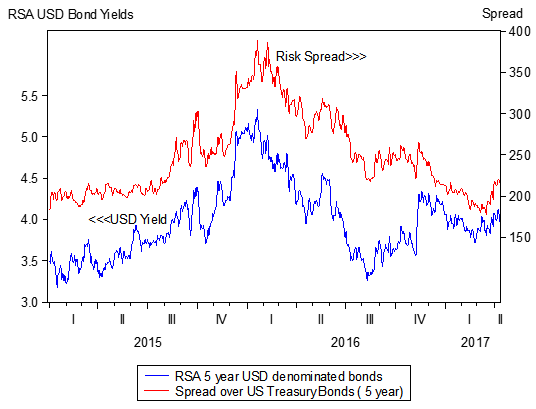

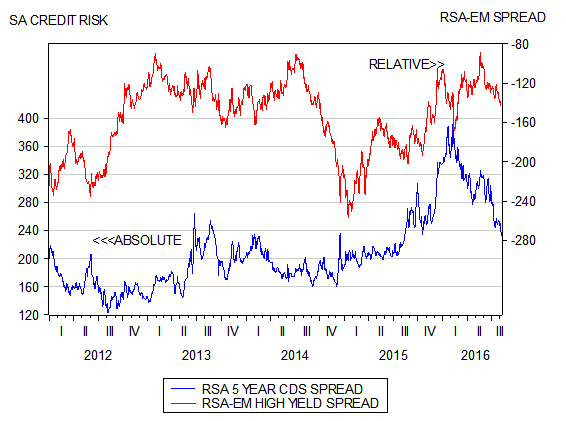

Another way of measuring risks would be to convert the calculation of required returns and risk into to much less inflationary USD. The yield on US dollar denominated debt issued by the SA government provides an appropriate bench mark for measuring required risk adjusted returns on South African assets. As we show below these dollar yields rose significantly from around 3.6% in early 2015 to as much as 5.12% p.a. by year end. Since then this rate has receded but increased by a significant 36bp since mid- February. The cost of insuring SA 5 year dollar denominated debt against default, an accurate measure of real sovereign risk has followed a similar pattern rising from 1.82% p.a at its lowest in 2017 to the current 2.15% p.a. That is when converted into USD an investment in a South African asset would be required to return over 2% p.a. more in USD than an equivalent US investment to justify its value.

Zuma risk measured in USD

Source; Bloomberg, Investec Wealth and Investment

More risks demand higher returns (sometimes described as the hurdle rate capital raisers have to leap over) and the higher the required returns the fewer investment projects will qualify – to the grave disadvantage of the economy and its growth prospects. The object of economic policy should be to reduce such risks rather than to raise them- something the Zuma presidency has clearly failed at.

These required returns that add business risk to sovereign risk may also be regarded as the discount rate used to present value any flow of income from businesses or government agencies. The higher the discount rate attached to SA assets the less they are worth. Adding risk makes SA immediately poorer as well as undermining their income prospects as less is invested in SA projects that could add to incomes and demands for labour.

Yet given the reactions of the credit rating agencies that have down rated SA credit indicating a higher probability of default on our debt these market reactions as we have identified them must be regarded as surprisingly subdued.

The rand, and the market in RSA bonds, clearly benefit to a degree from the prospect that Zuma might not survive the campaign to remove him. Were Zuma certain to stay rather than possibly go, we would be facing even more risk aversion more inflation expected, higher interest rates and a very likely recession as confidence in the prospects for the SA economy ebbed away.

Were Zuma to go the benefits could extend well beyond the promise of a revival of fiscal rectitude and less inflation and lower interest rates. It would offer the prospect of a radical economic transformation. By which I mean the cleaning of the Aegean stables that the State Owned Companies (SOC’s) have become. It would not require any Hurculean effort to do. A few investment bankers could do the job of converting the SOC’s into ordinarily valuable and well managed business. So converting them into assets from their current state of very expensive and potentially ever larger liabilities, that SA tax payers and consumers have to cover. Converting these burdens into private businesses that will compete for their custom, that will be run efficiently and deliver their goods and services at lower competitive prices – as business have to do to survive the market test would be a large plus for South Africans. And they would become taxpayers rather than incur vast contingent liabilities that damage our credit rating and raise our costs of finance.

Can any SA seriously believe that these SOC’s are essential to the purpose of developing the SA economy? Or fail to understand that their actions are driven by the narrow interests of their managers and employees and what their suppliers can extract from them. Their monopoly powers that make this behaviour possible need to be removed by breaking them up into smaller units by selling off their assets to a variety of owners and operators. And the capital to fund these purchases will be abundantly available from domestic and foreign capital providers at market determined values.

The proceeds from their privatization could be used to pay of much of SA’s debt and dramatically reduce the interest burden of serving it and open up the prospect for genuine poverty relief. This transformation – turning great weakness into strength – would help raise the growth potential of the SA economy – and truly transform the economic prospects of all South Africans