21st January 2019

Benign expectations of inflation and interest rates despite low rates of unemployment

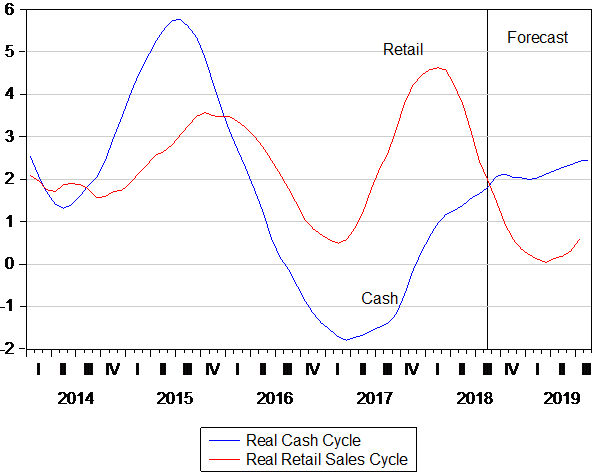

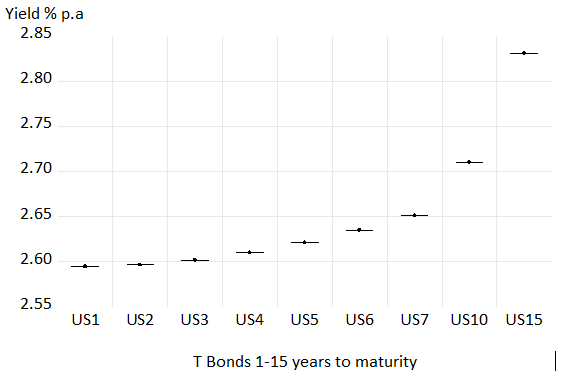

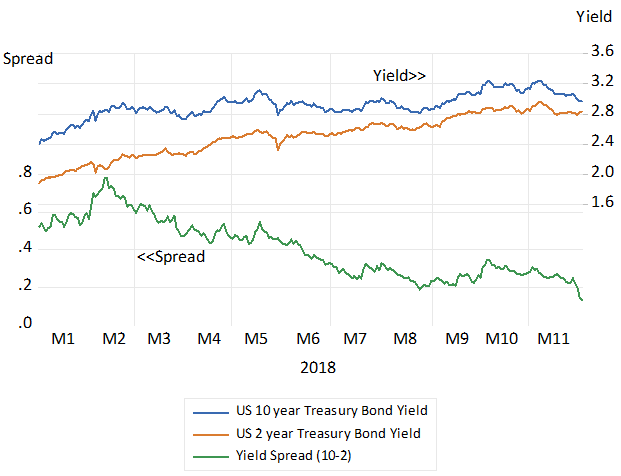

The US capital market in January 2019 reveals a very benign view of inflation and of the direction of interest rates. The long- term bond market indicates that inflation is expected to stay below an average 2% per annum over the next ten years. The difference between the yield on a vanilla 10 year Treasury on January 9th (2.71% p.a) and an 10 year Inflation protected US bond that day (0.833% p.a) is an explicit measure of inflation expected in the bond market. This yield spread gives long term investors in US Treasuries a mere 1.88% p.a extra yield for taking on the risk that inflation will reduce the real value of their interest income. And the Fed is confidently expected not to raise short term rates this year. The money market believed in January 2019 that there was only a one in four chance of the Fed Funds rate rising by 25 b.p. this year. On January 9th 2019, the one year treasury bond yield of 2.59% p.a. was expected to be only marginally higher, 2.66% p.a in five years. [1]

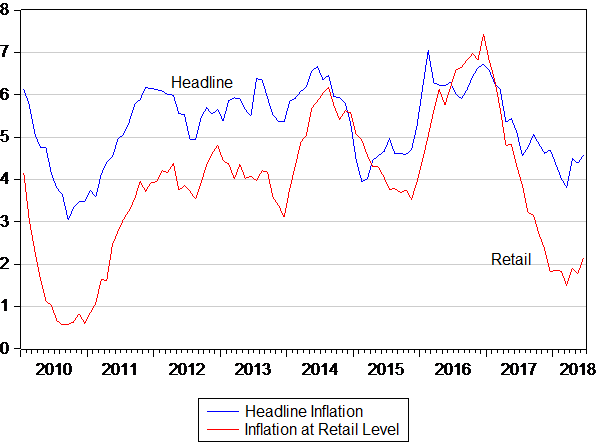

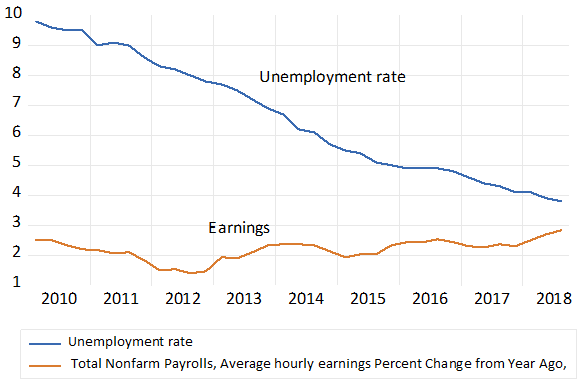

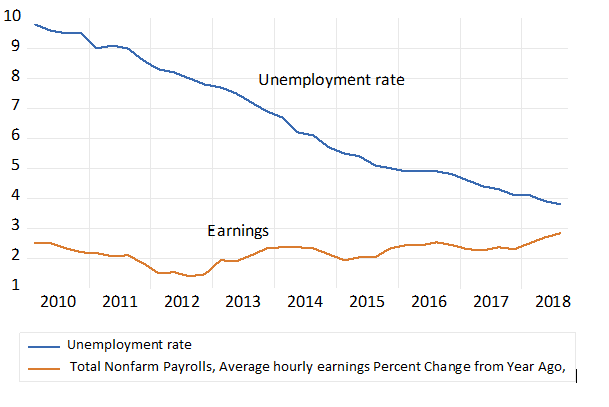

Are such views consistent with a very buoyant labour market it has been asked? Unemployment rates are at very low levels, below 4% of the labour force while average earnings are rising at about 3% p.a. These bouyant conditions in the labour market may portend more inflation and higher interest rates to confound the market consensus.

Fig. 1: The US Treasury Bond Yield Curve on January 9th 2019.

Source; Reuters-Thompson and Investec Wealth and Investment

Figure 2; Unemployment and earnings growth in the US

Source; Federal Reserve Bank of St.Louis, Fred data base and Investec Wealth and Investment

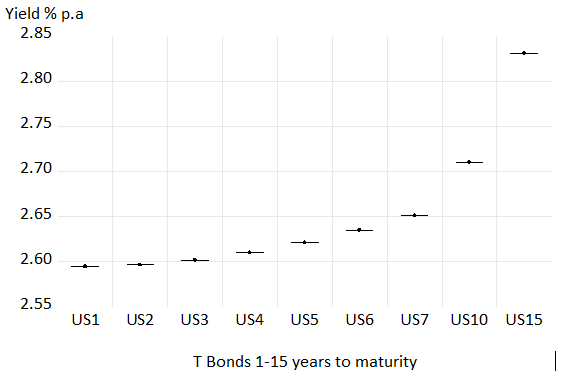

The relationship between wages and prices in the US

Do changes in prices lead or follow changes in wage rates in the US? The economic reality is that they both follow and lead. Both the price of labour – average wages and other benefits per hour of work and its cost to employers- and the price of a basket of goods and services, represented by the CPI, are determined more or less simultaneously and inter-dependently in their market places. As we show below the index of average wages and the CPI are highly correlated. How they interact is not nearly as obvious and may not be consistent enough to make for any convincing evidence of cause and effect- that is from prices to wages or wages leading prices.

The relationship between wages and prices and employment and GDP

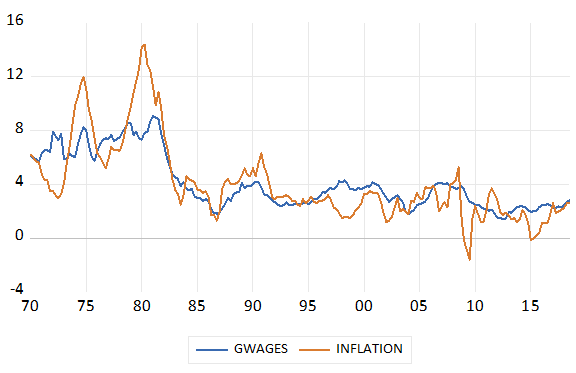

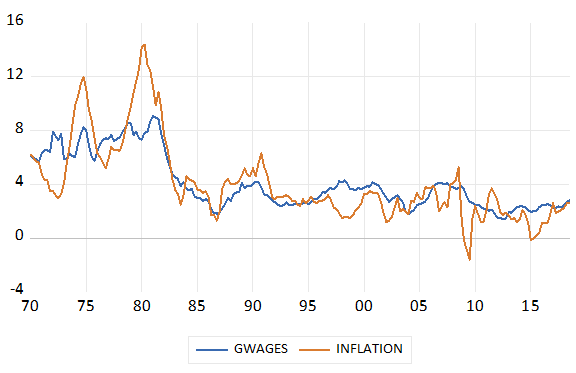

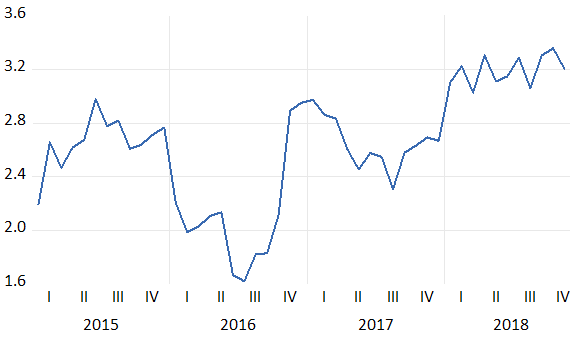

Fig.3 Wage and headline inflation in the U.S 1970-2018.3; Quarterly data, year on year percentage changes

Source; Federal Reserve Bank of St.Louis, Fred data base and Investec Wealth and Investment

As may be seen in the chart above wage inflation in the US ( year on year per cent changes in hourly earnings) appears to track headline inflation very closely and vice versa. Wage inflation has been less variable than headline inflation ( year on year change in the CPI) Headline inflation since 1970 has averaged 4.09% with a standard deviation (SD) of 2.95% p.a. while average wage inflation per annum has been a very similar 4.09% p.a, with a lower SD of 2.02% p.a.

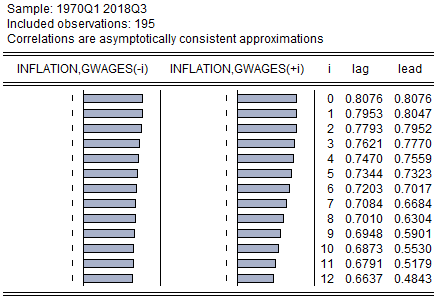

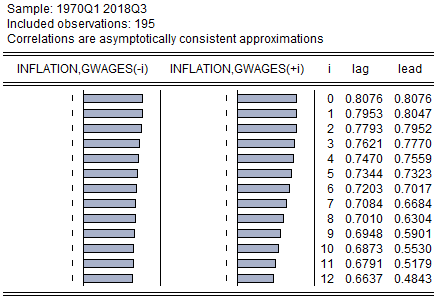

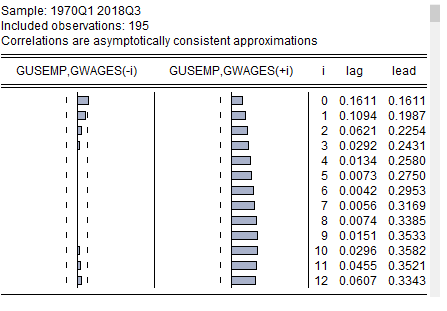

We show below a table of correlations of headline and wage inflation at different leads and lags. As may be seen the highest correlations are realized for contemporaneous growth rates. The correlations remain very similar for lags up to 12 quarters and point to no obviously important and reliable leads and lags that could inform any wage plus theory of inflation.

Table 1; Cross-Correlogram of inflation and growth in wages in the US. Quarterly data Y/Y percentage growth (1970.1-2018.3)

Source; Federal Reserve Bank of St.Louis, Fred data base and Investec Wealth and Investment

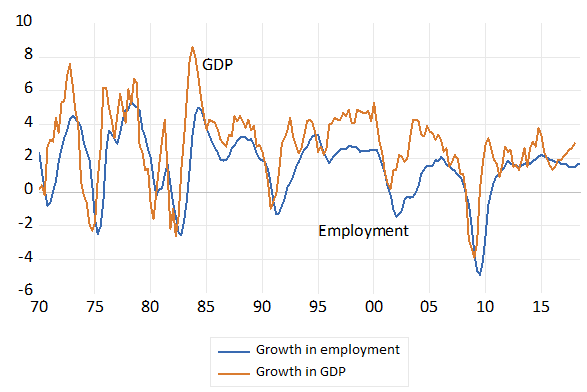

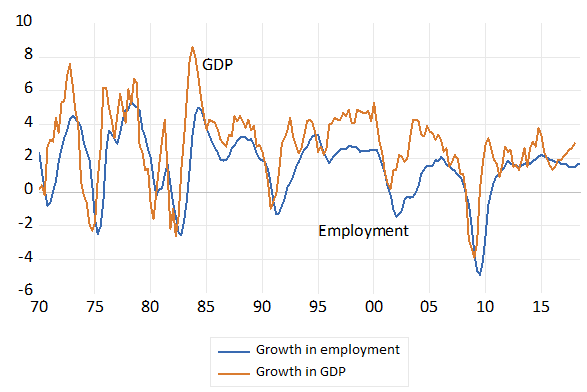

Fig.4 Growth in employment and GDP Quarterly data y/y percentage growth (1970.1-2018.3)

Source; Federal Reserve Bank of St.Louis, Fred data base and Investec Wealth and Investment

We show the very close relationship between the growth of payrolls and the growth in the U.S economy in the chart above. GDP has grown on average by 2.77% p.a since 1970 while employment has increased by 1.56% p.a on average since then. The correlation of the two growth series is 0.60 while, as may be seen, employment growth (SD 1.87% p.a) has been less variable than output growth (SD 2.18% p.a) GDP growth very consistently leads employment growth. The lag effect seems strongest at two quarters. The correlation between changes in GDP and changes in employment two quarters later is as high as 0.86.

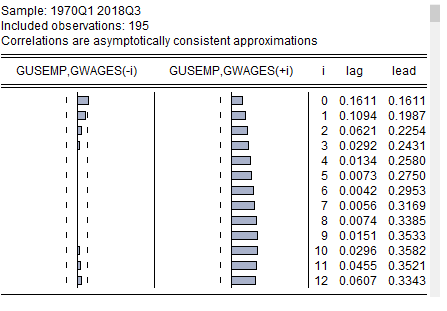

We show the lag structure in the Cross-Correlogram below

Table 2. Cross-Correlogram of Growth in Employment and Wages in the US. Quarterly data y/y percentage growth (1970.1 2018.3)

Source; Federal Reserve Bank of St.Louis, Fred data base and Investec Wealth and Investment

Why changes in wage rates and prices are so highly correlated

The markets for goods and the markets for labour have the general state of the economy in common. The wages and prices that emerge in the markets for labour and goods and services will be influenced by how rapidly the demand for and the supply of all goods, services and labour may be growing. Furthermore higher wages or prices will in turn restrain demands for labour and other goods and services effecting the observed wage rate and employment outcomes in the labour market.

Changes in prices, wages and interest rates have their causes (represented in the conventional supply and demand analysis by leftward or rightwards shifts in the demand and supply curves that cause prices to rise or fall) But any such shock to prices or wages or interest rates and asset prices will also have effects on demand or supply, as prices move higher or lower. Such effects can be represented by movements along the relevant demand or supply curves.

The essence of any helpful analysis of supply and demand forces at work is to recognize and identify the sequence of events that lead to any new equilibrium price when supply and demand are again in balance . That is to identify the initial causes of a price change, the supply side or demand side shock that gets prices or wages or interest rates moving in one or other direction, and their subsequent effects on prices and the further adjustments made by buyers and sellers to the shocks. An unexpected spurt of economic growth may well lead to more employment and higher real wages. That is cause a shift rightwards in the demand curve for labour. Higher real wages then serve to ration the available supply of labour under pressure from increased demands.

These higher wages may induce more potential workers to seek employment. Such responses would make the supply curve of labour more elastic in response to higher wages. Thus more worker employed will help offset the initial wage pressures emanating from the demand side of the market .

Supplies of goods and services and capital and labour may also come from abroad to add to supplies and so influence prices on the domestic markets. Trade and capital flows may alter the rate of exchange that, depending on their direction, may add to or reduce the price of imports in the local currency. And exports can add to demands – so competing with local buyers and to possibly price them out of the local market. It is demand and supply that determine prices and wages. The changing state of domestic demand may not be enough to push prices or wages consistently higher. The final outcomes for prices will also depend on the supply side responses.

Furthermore prices are not simply set as a pre-determined percentage higher than the cost of producing them. Of which the costs of employing workers may be a more or less important part, depending on the labour intensity of production. The state of the economy (demand) and the competition to supply customers will determine how much margin over costs will their way into the prices any firm will charge.

Costs to some firms are the prices charged by their suppliers- including their employees. The distinction between what may be described as costs, or alternatively prices, will be based on the position the buyer or seller occupies in the supply chain. In the very long run prices and the costs of supplying all goods or services offered will tend to converge. The relevant cost to be covered will include the opportunity costs of employing capital as well as labour.

Is it a matter of demand pull or cost push on prices- or is it both – with variable difficult to predict lags between prices and costs or costs and prices? The evidence of wage and price growth trends says it is both as would any full theory of wage and price determination.

Another force common to prices wages and interest rates is the increase in prices and wages expected in the future. The faster they are expected to increase the more workers and firms and investors for that matter will wish to charge upfront for their services. All this complexity makes any uni-directional wage or cost-plus theory of inflation of very limited explanatory or predictive power.

The Phillips curve – origins and uses.

There is an economic theory known as the Phillips curve, that predicts that decreases in the unemployment rate (increases in the demand for labour) would cause wages to rise faster and for prices and interest rates to follow. The original paper written in 1958[2] was primarily an exercise in innovative, early econometrics. It demonstrated how curves could be fitted to annual data on changes in wages and the unemployment rate. It showed a broadly negative relationship between wage rates and the unemployment rate. The theory was that increased demands for labour- represented by a lower unemployment rate -would lead to higher wages.

The data extended over a long run, 1861-1957. It was collected over a period when the United Kingdom was mostly on the gold standard and when inflation would have been confidently expected to be sustained at very low levels. Of interest is that Phillips in his paper was well-aware of the role variable import prices might play in influencing prices and wages. A force we would describe today as a supply side shock.

It was this theory that Keynesian economists invoked in the sixties to argue that more employment could be traded of for more inflation. The idea was that workers, unwilling to accept the wage cuts that might restore full employment, might be fooled by inflation that surreptitiously reduced their real wages and so encouraged employment. Employment opportunities that were presumed to be structurally deficient – depression economics that is.

The classical economists regarded the flexibility of wages and prices in the downward direction as the cure for recessions. The extended unemployment of the nineteen thirties appeared to indicate that any reliance on wage and price flexibility to restore full employment was unrealistic. Given that nominal wages were seen as rigid in the downward direction meant persistently high levels of unemployment. That is unless governments intervened to stimulate aggregate demand enough to cause inflation and thereby reduce real wages enough to encourage employment. The implications of the Phillips curve that appeared to trade higher nominal wages for more employment was generalised to imply a tradeoff of inflation for faster growth.

The predictive powers of the Phillips curve

The theory has had very poor powers of prediction- originally of what became high inflation and slower growth in the US and elsewhere in the nineteen seventies. Much higher average rates of inflation of prices and wages in the seventies were associated with much slower not faster growth. This lethal combination came to be described as stagflation. That inflation was accompanied by slower not faster growth encouraged monetarists with an alternative demand led rather than a wage led theory of inflation. The quantity theory of prices, reconfigured by Milton Friedman, regained its currency. [3]

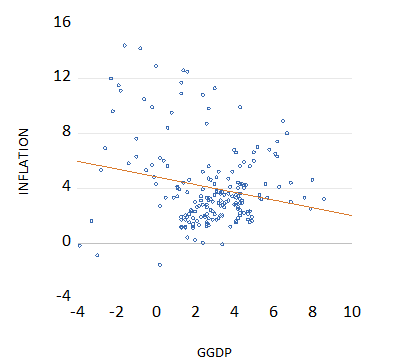

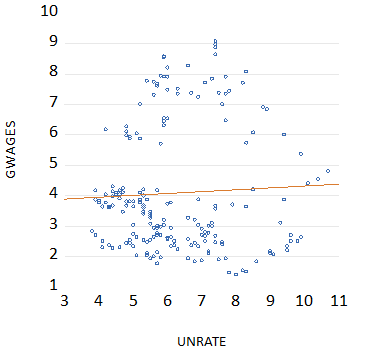

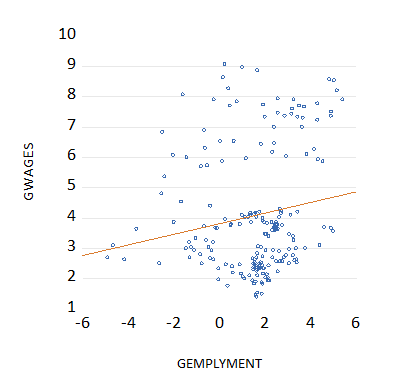

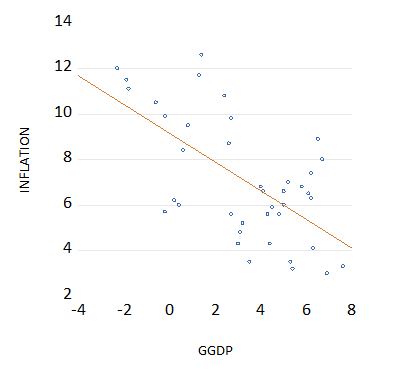

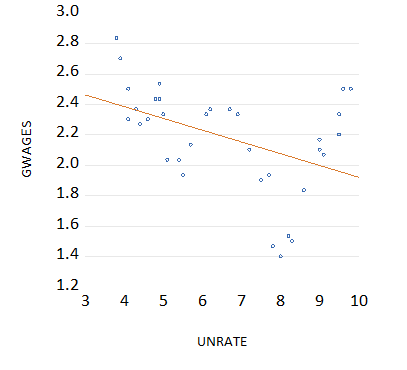

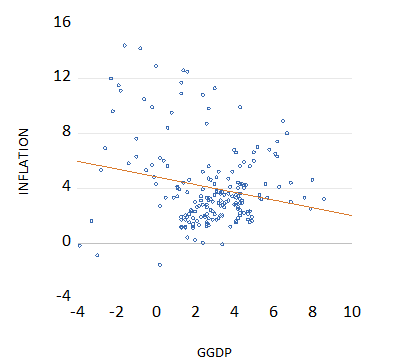

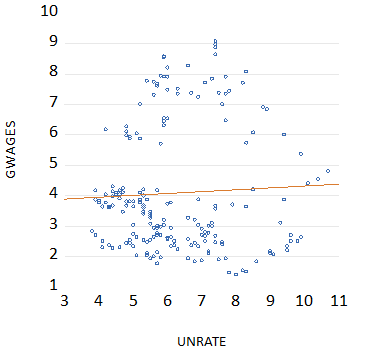

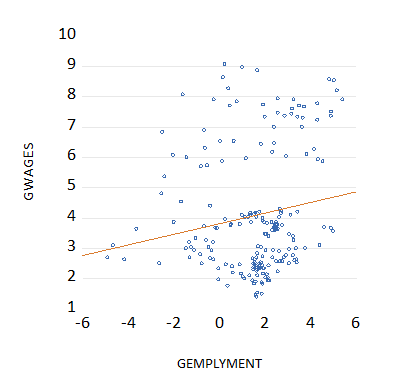

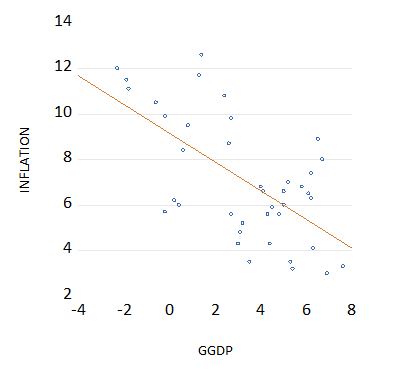

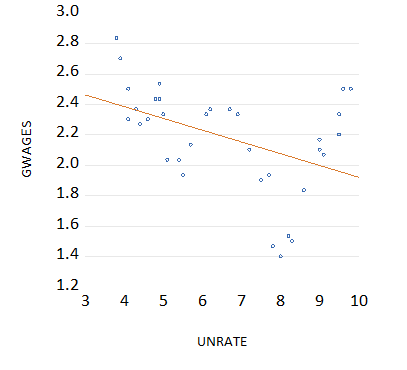

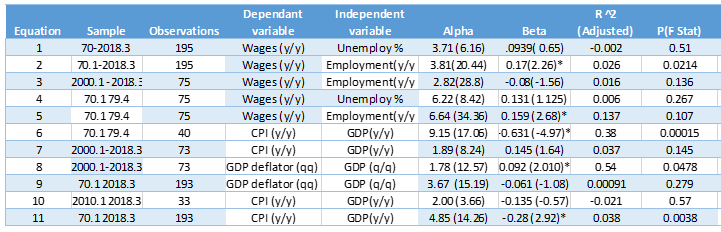

Any negative relationship between wages and unemployment (increased wage rates associated with less unemployment or more generally more inflation associated with faster GDP growth) in the US is conspicuously absent in the employment inflation wage growth and GDP data ever since the 1970’s and in-between. We demonstrate the absence of any support for the Phillips curve in the charts and tables below.

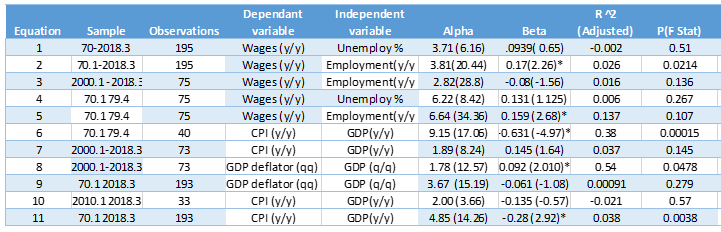

As may be seen the scatter plots and the regression lines that connect them indicate that unemployment and wage increases and inflation and GDP growth are not related in any statistically significant way. This is true of the relationship between unemployment (or employment) over the entire period 1970 – to 2018 and sub-periods including more recently between 2000 and 2018 and between 2010 and 2018. The correlations for the entire period and for sub-periods within them between wage growth and employment growth and between inflation and output growth are close to zero as may be seen in the table of regression results. The scatter plots and their regression lines shown below indicate the absence of any consistently meaningful relationships very clearly.

The table of regression results shown below confirms the absence of any predictable statistically significant relationship between employment and wage growth or between GDP growth and prices or indeed vice-versa. As may be seen the single equation regression equations are almost all explained by their alphas. The goodness of the fits of the regressions are very poor indeed. Their respective R squares that are all close to zero- indicating that the growth rates are generally not related at all. The betas that determine the slope of the regression lines are of small magnitude and most do not pass the test of statistical significance at the 95% confidence level – and some that do, for example equations 6 and 11, indicate that the relationship between wage growth and employment is a negative rather than a positive one. The presence of serial correlation in the equations as demonstrated by the Durbin-Watson (DW)statistic indicates that these betas may well be biased estimates. It would seem very clear that there is no trade-off between wage and price growth and the growth in output and employment in the US. Any forecast hoping to predict inflation via recent trends in wage rates or employment would be ill-advised to do so, given past performance.

Fig.5; Inflation and growth in real GDP Quarterly Data Growth year on year. Scatter Plot and Regression line (1970.1 2018.3)

Source; Federal Reserve Bank of St.Louis, Fred data base and Investec Wealth and Investment

Fig 6: Growth in wages y/y and the unemployment rate 1970.1 2018.3 Scatter Plot and regression line

Source; Federal Reserve Bank of St.Louis, Fred data base and Investec Wealth and Investment

Fig.7; Growth in wages and growth in employment (1970,1 2018.3) Scatter Plot and regression line

Source; Federal Reserve Bank of St.Louis, Fred data base and Investec Wealth and Investment

Fig.8; Inflation and growth in GDP (1970-79) Scatter Plot and regression Line

Source; Federal Reserve Bank of St.Louis, Fred data base and Investec Wealth and Investment

Fig 9; Growth in wages and unemployment rate (2010.1 2018.3) Scatter Plot and regression line

Source; Federal Reserve Bank of St.Louis, Fred data base and Investec Wealth and Investment

Table 2; Regression results

[4] The data is downloaded from the St Louis Federal Reserve data base Fred. The data is quarterly and seasonally adjusted and all growth rates have been calculated by Fred and downloaded into Eviews. Eviews was used to run the regression equations and construct the charts. Wages were represented by average hourly earnings of production and nonsupervisory employees in the private sector. (AHETP) Employment by Total Nonfarm Payrolls (PAYEMS) The unemployment rate (UNRATE) is the civilian unemployment rate. The GDP and CPI have their conventional descriptions

Not inflation- only unexpected inflation has real effects on output and employment

That is because firms and workers build inflation into their wage and price settings. Much faster inflation in the seventies did not come to surprise workers and did not mean lower real wage costs for the firms that hired them. Moreover prices rise faster as they did in the seventies, as the oil price rose so dramatically, when Middle East producers exercised their newly found monopoly power to restrict supplies. Negative supply side shocks that raise prices and reduce demand will complicate the relationship between price and wage changes.

A larger positive supply side shock for the global economy that caused downward pressure on prices was the entrance of China and Chinese labour and enterprise into the global economy. It brought a very large increase in the supply of goods- especially of manufactured goods. This addition to supplies at highly competitive prices lowered the prices established producers outside of China have been able to charge and forced many of them out of business.

The challenges for the economic forecaster

It is possible to build more complex multi- equation models that incorporated lags between GDP growth and employment growth and between changes in prices and wages to hopefully forecast inflation and growth. That is consistently with economic theory combined supply and demand forces and their feed-back effects with due importance attached to inflationary expectations and how they are established. If the feed-back effects however accurately identified are themselves of variable force through different phases of the business cycle the estimates of the equations are unlikely to deliver statistically meaningful results.

The accuracy of such forecasts will depend not only on the internal logic of the equations estimated, but on the assumptions made about the forces outside the model. The predictive power of such models must be tested out of the sample periods over which the coefficients of the model were estimated. Forecasters inside and outside of central banks have every incentive to make accurate forecasts of inflation, growth, interest rates and asset prices. The ability of any of these models to consistently beat the market place has to date never been obvious. And were they so able the market itself would become less volatile.

Inflationary expectations and the reactions of central bankers[5]

The importance of inflationary expectations in the determination of the price and wage level has much impressed itself on central bankers. They recognized that there was no output or employment benefit to be gained from more inflation. That only unexpectedly higher inflation might stimulate more output- and unexpectedly low inflation will do the opposite. The central bankers have come to understand that their ability to surprise the market and their forecasts is very limited. Given that is the importance workers (trades unions)and firms with price or wage setting powers would attach to predicting inflation as accurately as possible. They do so in order to avoid the potential income-sacrificing consequences of underestimating or over estimating inflation. Underestimating the inflation to come would mean setting wages and prices below where market forces might have justified. Overestimating inflation might mean wages and prices having to reverse direction with a consequent loss of output and employment. Successfully second -guessing central bank action that helps determine the rate of inflation is an essential ingredient for successful market makers.

When the surprises are revealed they will come with losses of output and employment as the market adjusts or in the case of surprisingly rapid inflation exchange rate weakness and higher interest rates will follow. Dealing with such surprises adds volatility to prices and asset prices. A risky environment discourages savings, inward capital flows and investment and reduces potential output and its growth.

Thus central bank wisdom is that they should avoid as far as possible inflation shocks and associated monetary policy actions that might surprise the market place. Rather they have come to understand that their task is offer the market place a highly predictable and low rate of inflation in the interest of permanently faster growth rates. Hence inflation targeting.

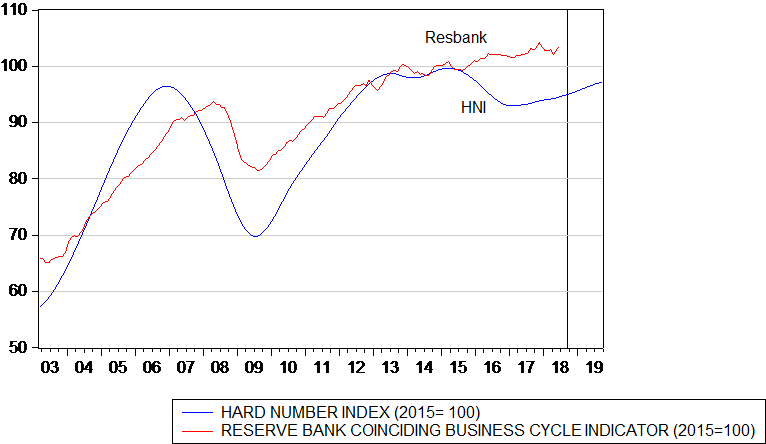

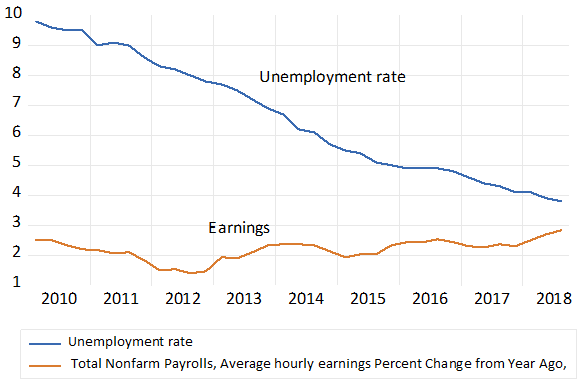

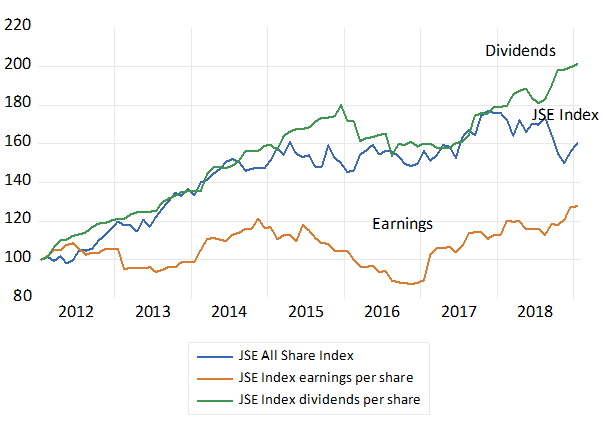

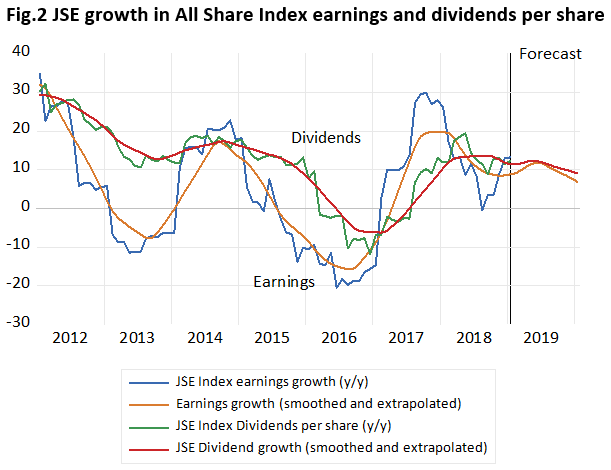

A South African post-script

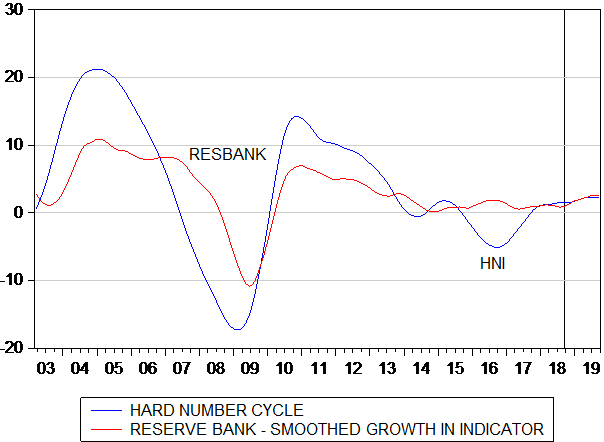

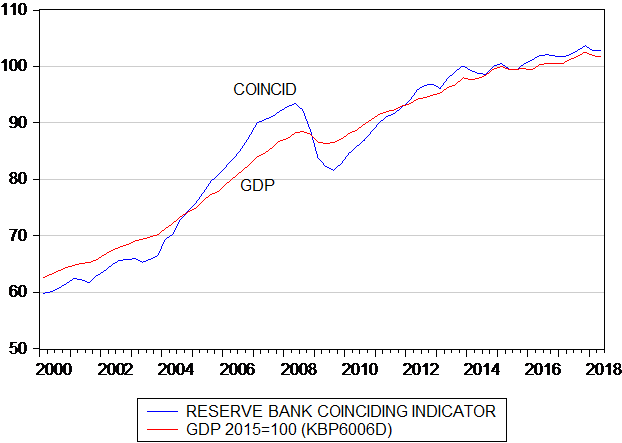

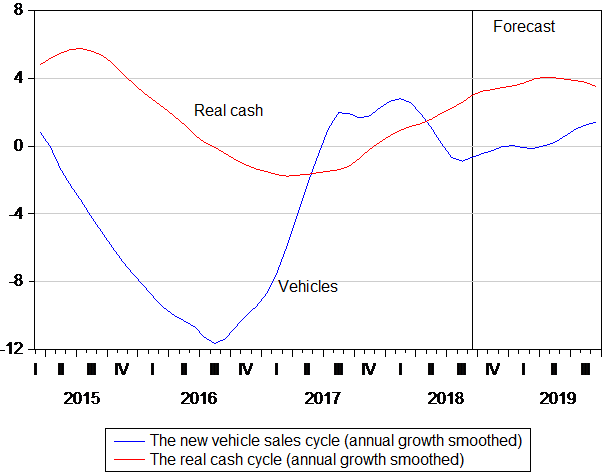

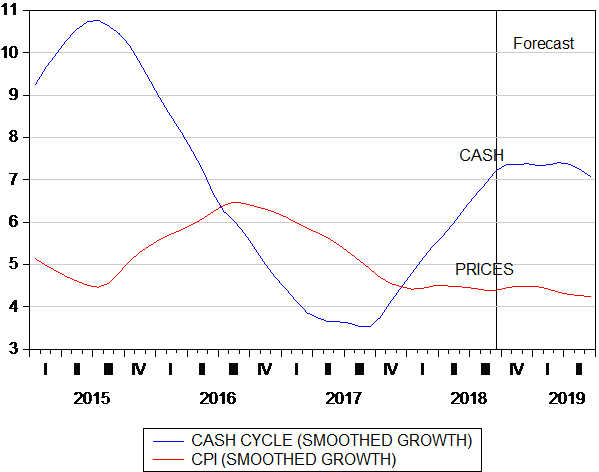

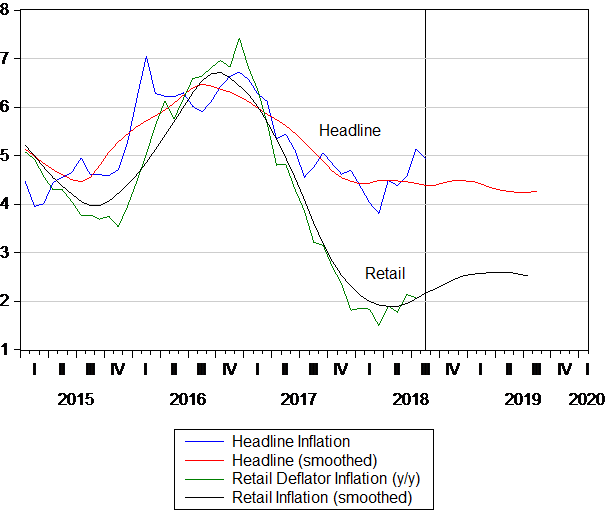

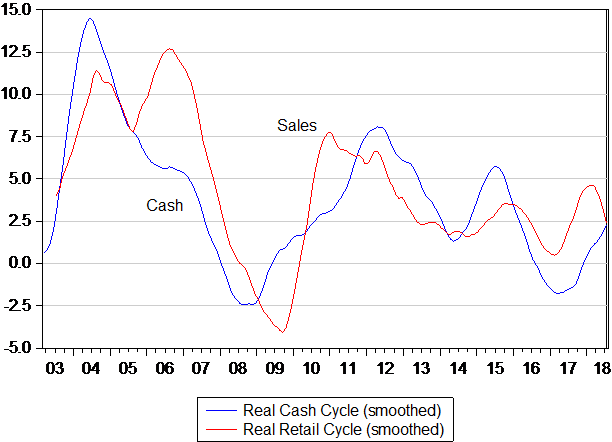

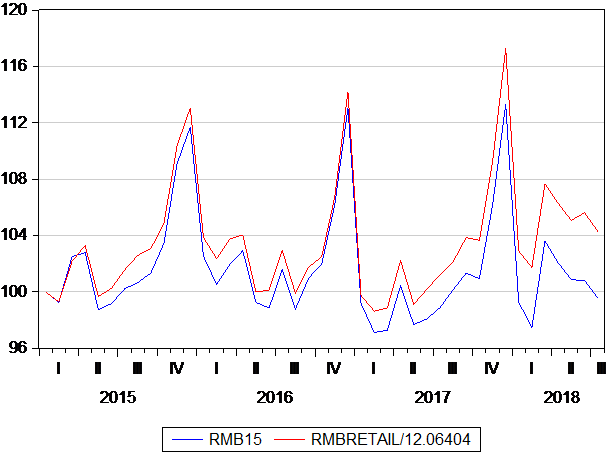

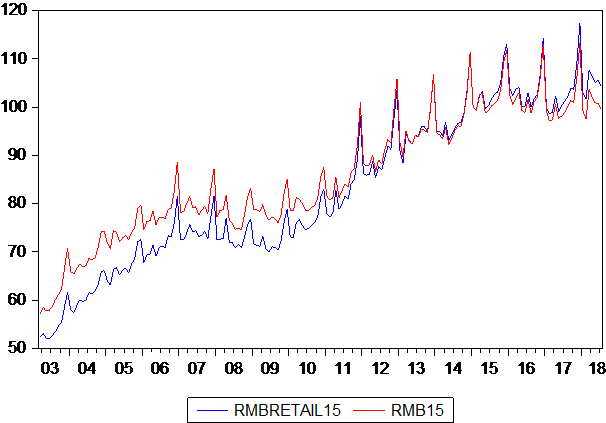

This is the objective of the SA Reserve Bank -enshrined in our constitution – as we have been well reminded recently. But success in achieving balanced growth does demand more flexibility than the SA Reserve Bank has demonstrated. The flexibility to recognize that powerful and frequent supply side shocks to inflation – exchange rate, oil price and food price shocks call for very different interest rate responses than when demand is leading inflation.

Alas demand led inflation has been conspicuously absent in recent years. Wage increases in SA therefore explain unemployment not inflation. Accurately forecasting inflation in SA – better than the Reserve Bank has been able to do – means anticipating the exchange rate and the oil price and rainfall in the maize triangle. A near impossible task it may be suggested. Eliminating demand led inflation ( policy settings that attempt to balance domestic demand and supply) rather than directly aiming at an inflation rate that is largely beyond its control is a much more realistic and appropriate task for the SA Reserve Bank. And the market place can fully understand these realities. Inflation forecast and so inflationary expectations in SA will be rational ones.

[1] By Reuters-Thompson interpolating the yield curve that is reproduced here

[2] A.W.Phillips, The relationship between unemployment and the rate of change of money wage rates in the United Kingdom, 1861-1957,Economica vol 25 (19580 pp 283-99

[3] My own interpretation of the analytical disputes of the time can be found in my Rational Expectations and Economic Thought, Journal of Economic Literature, Volume XV11 9December 1979),pp 1422-1441 it referred to the pioneering work on the role of expectations in macro-economics of Milton Friedman (1968) and Edmund S.Phelps (1967 and 1970)

[4]

[5] See my, The Beliefs of Central Bankers about Inflation and the Business Cycle—and Some Reasons to Question the Faith, Journal of Applied Corporate Finance; Volume 28, Number 1, Winter 2016

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)