The destruction by fire of historic buildings on the campus of my alma mater, the University of Cape Town, has brought home for many the cultural and societal value that lives in so many historic buildings.

It’s not just runaway fires that destroy beautiful old buildings though. Humans willfully do so too. My wonderful wife Shirley and I frequently regret the demolition of those interesting older Cape Town inner-city buildings we fondly remember; buildings that have been replaced by non-descript office blocks. The ornate faux Granada, Alhambra, on lower Riebeeck Street that doubled as a cinema and was our largest concert venue (seating about 3,000), provides one set of memories of times past.

It was replaced by a very conventional and boring office block that now looks and will probably soon qualify for demolition or conversion into apartments. It has no redeeming architectural features and I would suggest not even decent rentals to justify its survival or maintenance.

The willing – and at the time quite uncontroversial – destruction of many an iconic Cape Town building was a reflection of a very limited cultural sensitivity. The redevelopment and widening of lower Adderley Street, a once charming, essentially narrow main shopping street for the city, to make way for a new railway terminus, was a particularly egregious example of insensitive narrow-minded urban planning.

Master plans that often go wrong are a danger to the natural evolution of the built environment, as it proved to be, for inner city Cape Town. The old Cape Town railway terminus was a Georgian masterpiece. It was demolished to make way for an expanse of uninteresting, and completely out of place, a bit of lawn, for looking at not sitting down upon.

Are preservation orders a fair process?

The cost of preserving an interesting building should be borne by the taxpayer not its owner. In other words, full market value should be offered when making a compulsory purchase of a building of historical interest, a market value that would include the value of the redevelopment opportunity. The loss of wealth that would come with freezing the development opportunity, so reducing the value of the house or commercial building, should not be imposed on the owner. Owners who will see the value of their home, perhaps representing a large part of their savings that they were depending on for retirement, decline significantly because redevelopment of the site has now become impossible.

Scarcity that comes with time and redevelopment can add value to an older structure

A particular building style that was once commonplace, for example Victorian, Georgian or Cape Dutch homes that were the fashion of their day, become less common over time with redevelopment and the introduction of newer, more favoured styles. Styles change understandably and naturally in response to newly available technologies and materials. This fading away of the past and the falling number of structures that reflect the past therefore should add to the rarity (and scarcity value) of traditional buildings and hence their resistance to redevelopment.

Scarcity and the higher rents the iconic building might attract can add to the business case for preserving at least the facades of such increasingly rare and admired buildings. The more valuable the building, the less likely it will be demolished.

I think of the attractive facades of the still many art deco apartment blocks in Vredehoek, an inner city suburb of Cape Town, that must make them more desirable to rent and therefore more valuable to their owner-occupiers (Incidentally, the particular walk-up block of flats in Vredehoek where I spent my first five years (1942- 47) is still intact).

I wonder how well these then unusual art deco blocks of flats were received in the 1930s and 1940s when they were constructed, on mostly vacant land. Perhaps they were welcomed as representing worldly progress, not resisted as a threat to established land and home owners.

The economics of redeveloping property and the case for demolition

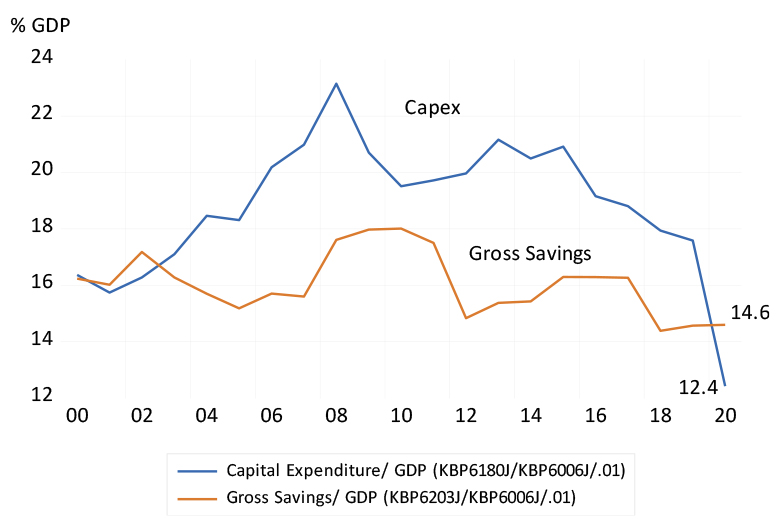

The test of the quality of any building or architectural feature will be its ability to command interest and respect from later generations. Most new buildings are commissioned with an expected economic life of about 20 years, given current interest rates. A building would be given a much longer life to prove itself, if the interest rates and political and inflation risk premiums incorporated in high borrowing costs in SA were lower. If an investment in a new structure in SA cannot be justified with 20 years of expected rental income, enough net rental income to cover the costs of a new building, plus the costs of purchase of the land or the building to be demolished, it will not now be built. If it can last beyond 20 years, it will be evidence of the superiority of the original design that will have added value to the building.

A building might be demolished when it is worth less than the land it occupies. A building would be valued as the present value of the expected or implicit rental income it could generate when owner-occupied, and discounted by prevailing interest rates (or more generally discounted by the returns available from similarly risky investment opportunities, by so called capitilisation rates). Demolishing the building releases the land for alternative use. It makes new buildings possible, with the potential to create a greater stream of net rental income with a higher present value: a present value of net rental income value that would have to be expected by some risk-taking developer to be high enough to make a profit. In other words, a building whose subsequent market value would exceed the value of the lost income from the existing structure, after adding demolition costs and to recover the cost of the new building.

At any point in time, the vast majority of buildings do not qualify in this way for redevelopment and demolition. Hence, as can be observed, older buildings mostly remain standing for much longer than the 20 years of economic life that brought them into being. A burst of property redevelopment activity is always a good sign of economic progress under way. It informs us that the land is becoming more productive and capable of commanding higher rental incomes, or the equivalent, capable of bearing higher implicit rentals for their owner-occupiers. It is a trend that’s helpful to property owners but a threat to those hiring accommodation or intending to enter the ranks of owner-occupiers.

How to deal with the “nimby” crowd and facilitate value-adding property developments

Therefore politics, plus the expected higher costs of renting or owning, may frustrate the intending developer. The “nimby” crowd (“not in my back yard”), may not favour redevelopment because it threatens the value of their own real estate nearby. But frustrating the conversion of land from less to more productive uses, as with all such interventions that prevent value adding innovations, will mean wasted opportunity and slower economic growth.

I have long thought that the higher wealth tax receipts that come with more valuable real estate should be shared in part with the owners of property in the neighbourhood. Extra revenue generated by higher wealth taxes collected on more valuable property can be shared with the local owners as compensation for the extra noise or traffic that the redevelopments may bring. Tax revenue that could be used to improve local parks or provide better local security or better access roads, in an obviously earmarked way, would help reduce resistance to redevelopment of the back yard that then becomes more desirable. This will mean more valuable buildings and gains in wealth for the owners of surrounding property.

It is also my contention that every generation of architects and builders should have the opportunity to impress upon the world the strength and beauty of their designs. Not all changes in design will be for the worse. Many may turn out for the better – only time can tell. A city must live and evolve – it cannot be frozen in time and kept as a museum for tourists. And a lively, economically successful city that can sustain good services to its citizens, with a mixture of the new and not-so-new structures, that have been allowed to respond to essentially market forces, can surely attract visitors as well as migrants from other cities.

Property development is part of an evolutionary process that will add to the capabilities of the city to provide additional work and income earning opportunities. Developments can add to the value of real estate to be shared between its owners (paying higher wealth taxes) and the local authority, applying additional tax revenue in generally useful ways.