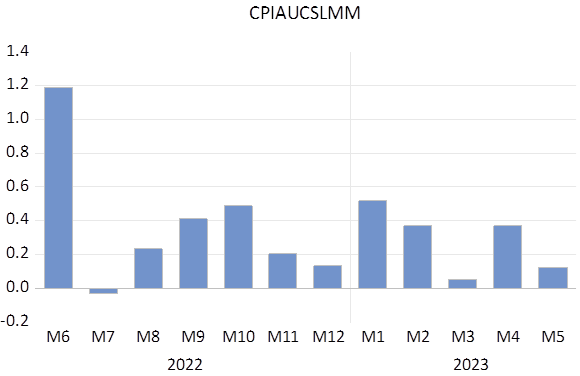

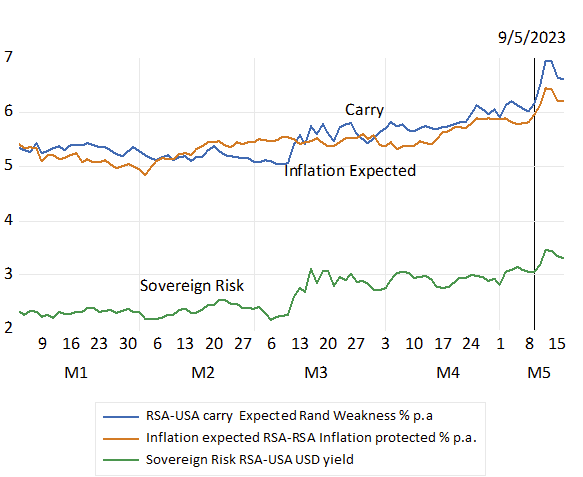

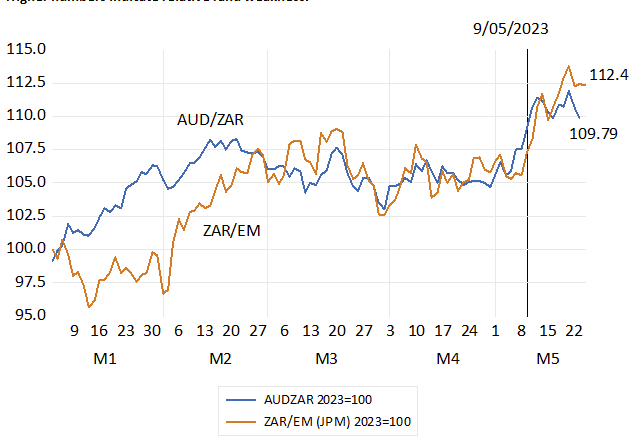

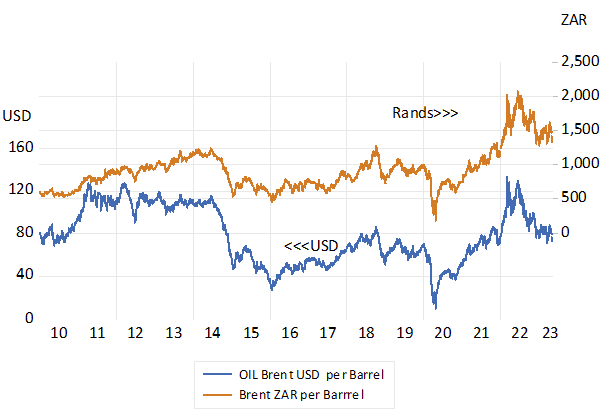

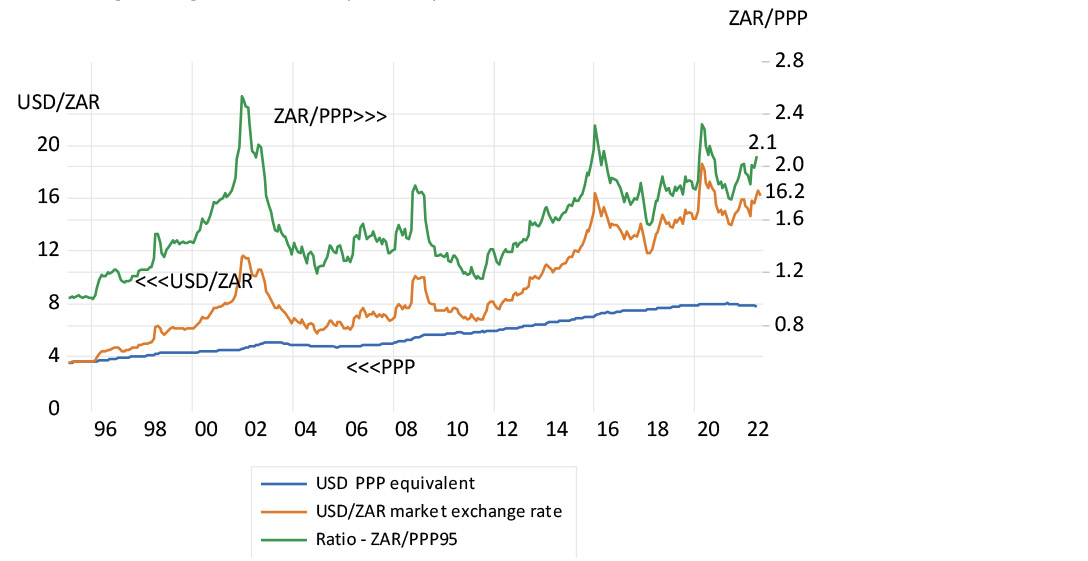

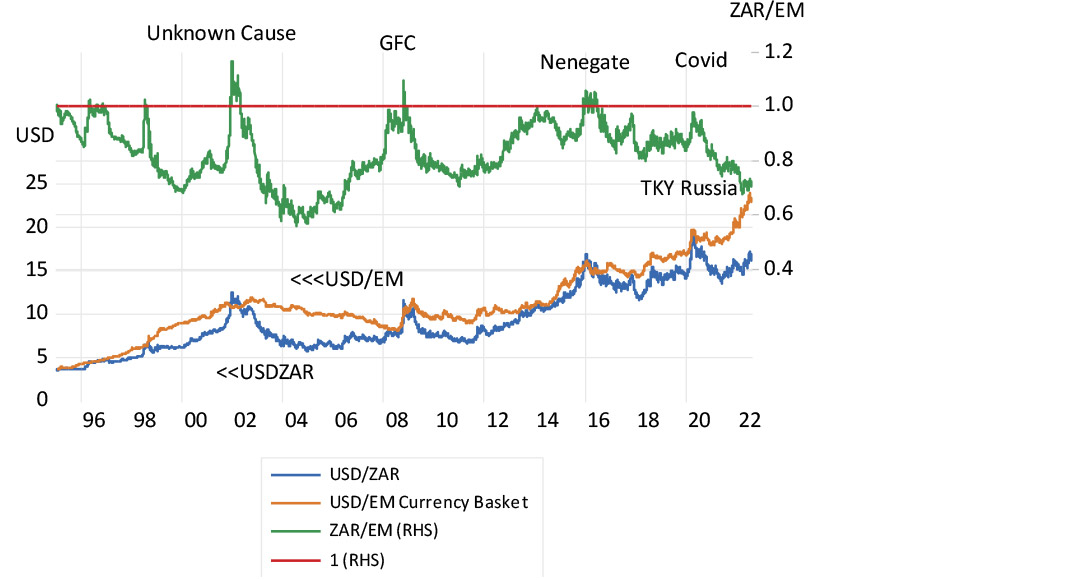

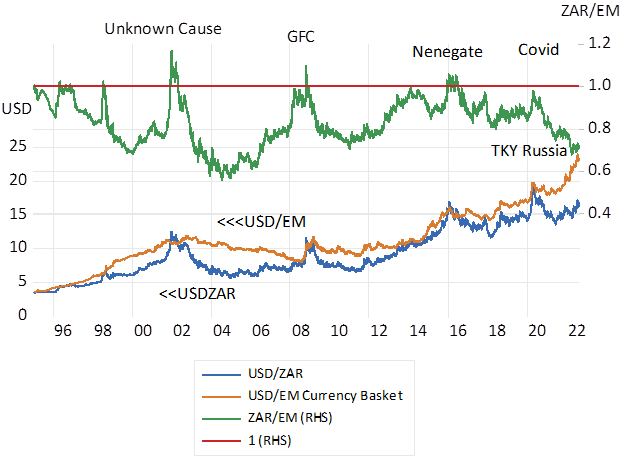

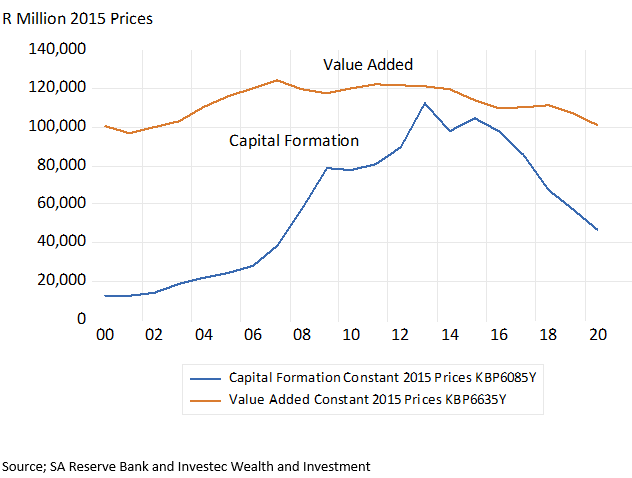

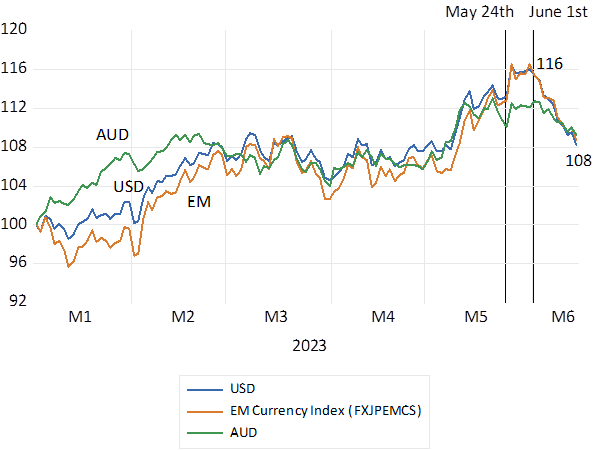

The rand has recovered strongly this month – by about 7% against the US dollar, and has performed similarly Vs the Aussie dollar and an index of EM currencies. The rand had weakened through much of 2023. It weakened by a further 3% when the SARB increased rates unexpectedly sharply by 50 b.p. on May 25th. Since June 1st the ZAR has recovered – as interest rates in SA have fallen away. arply.

The ZAR Vs The USD, the AUD and the EM Currency Index. (Daily Data January 2023=100)

Source; Bloomberg and Investec Wealth and Investment

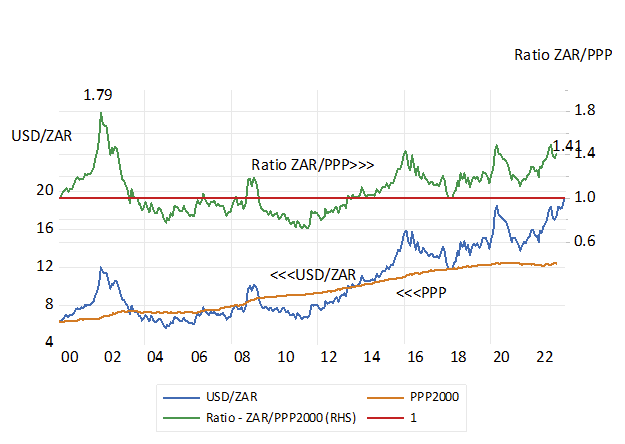

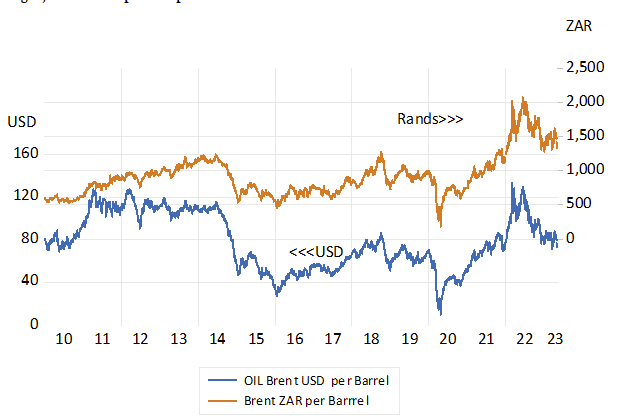

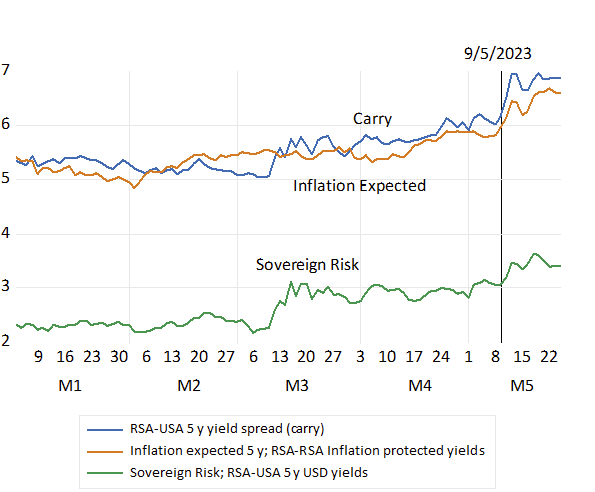

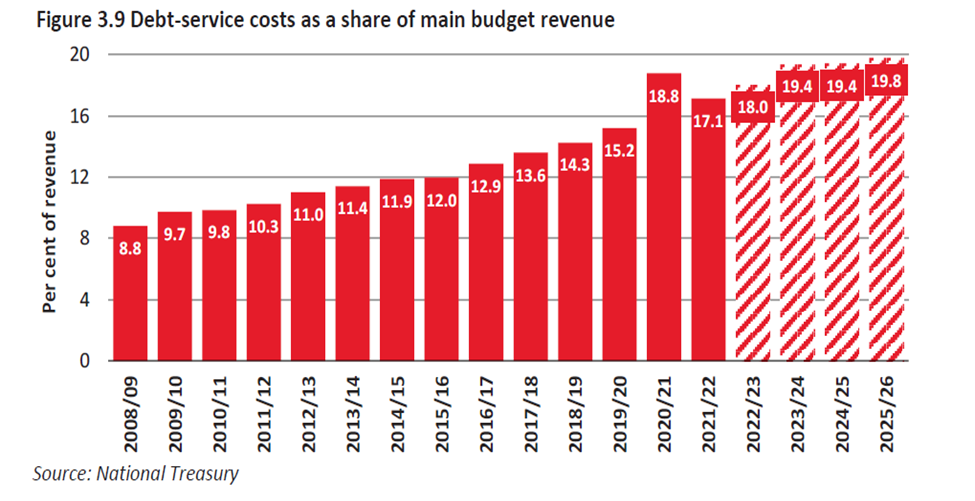

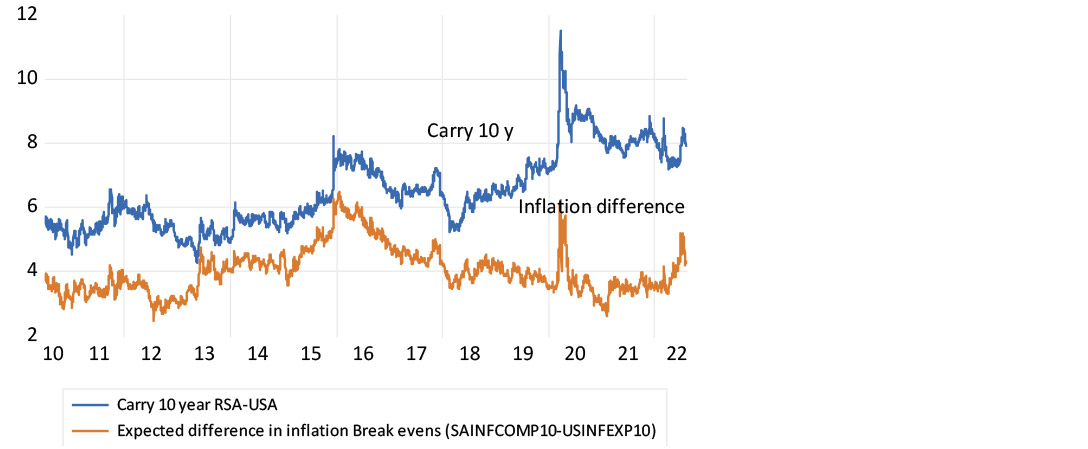

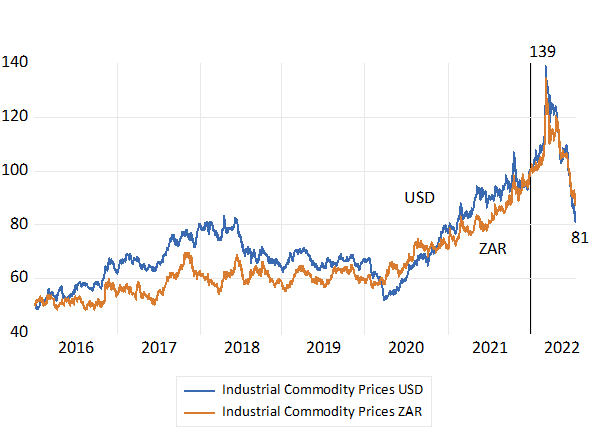

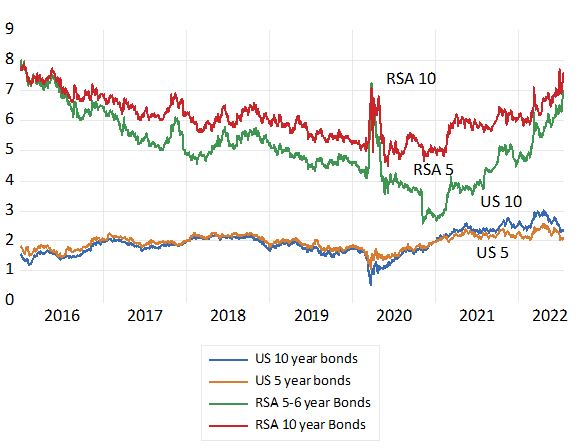

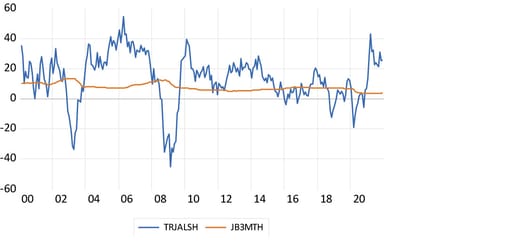

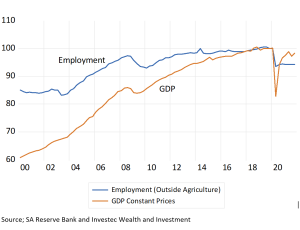

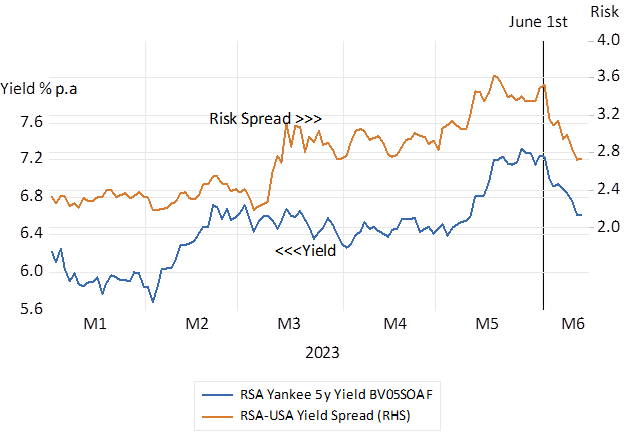

Long term RSA bond yields have declined significantly and helpfully by between 50 and 70 basis points this month. The Yankee Bond, a five year dollar denominated claim on the RSA, now yields a lower 6.4% p.a. compared to the 7% p.a. offered on June 1st. Moreover, the spread between the RSA dollar bond and a US Treasury of the same duration has narrowed significantly from 3.6% p.a to 2.8% p.a. This interest rate spread provides a very good indicator of the risks of default attached to SA bonds. More important perhaps for the direction of the rand and the economy has been the recent inflection in short-term interest rates. When the SARB raised rates on the 25th May, the money market, as represented by the forward rate agreements of the banks, immediately predicted a further one per cent hike in short rates over the next six months. The SARB is now expected to be much less aggressive. The market is now expecting short rates to rise by a quarter per cent.

RSA Dollar Denominated (5 year Yankee Yield) and the SA Sovereign Risk Premium (Daily Data 2023)

Source; Bloomberg and Investec Wealth and Investment

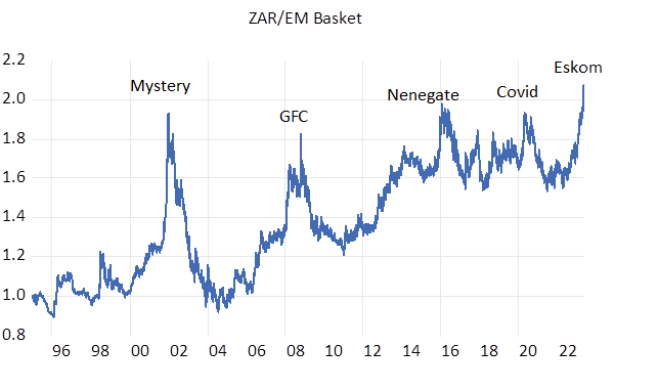

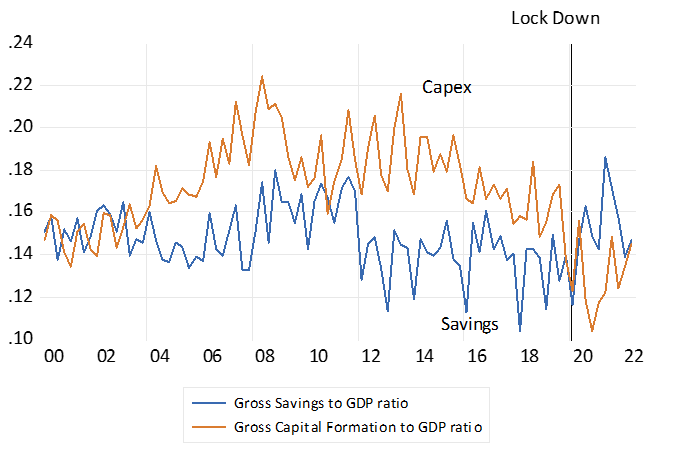

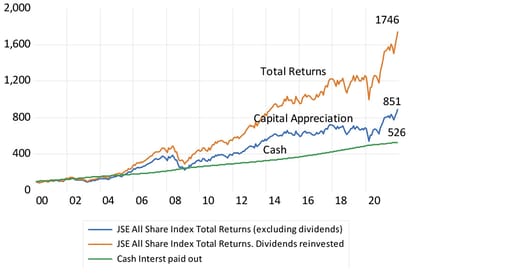

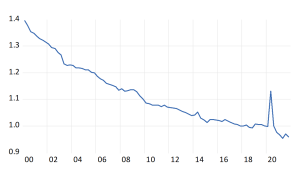

Why have surprisingly lower short term interest rates helped the rand as surprisingly higher rates clearly weakened the rand last month? There is much more than coincidence at work here. Higher short-term rates – higher overdraft and mortgage rates- combined with the higher prices that follow a weaker rand – are expected to further depress spending in SA and the growth outlook for the economy. The weaker the outlook for the economy, the weaker the growth in incomes before and after taxes, the more government debt is likely to be issued. And the graver becomes the eventual danger a of a debt default. For which still higher interest rate rewards have to be offered to investors to compensate them for the additional risks implied by a deteriorating fiscal condition. These higher interest rates then raise the cost of capital for SA business – making them still less likely to undertake growth encouraging capex.

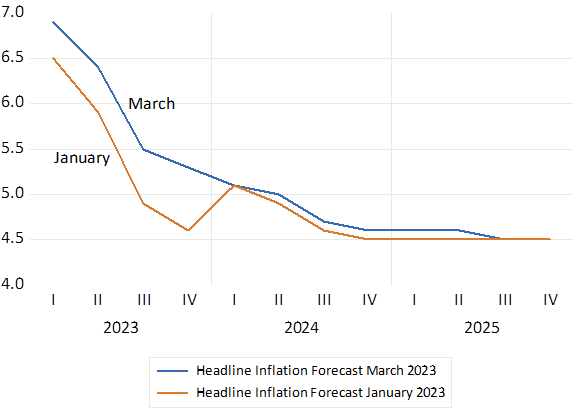

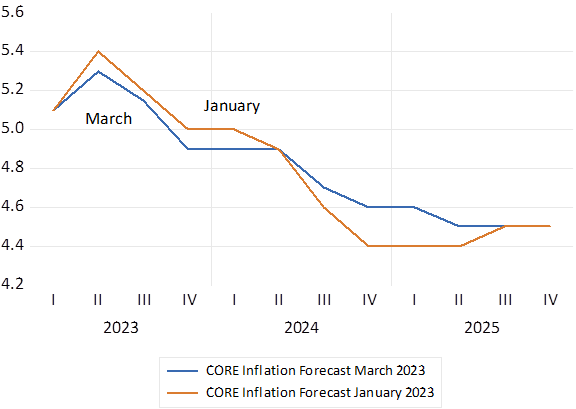

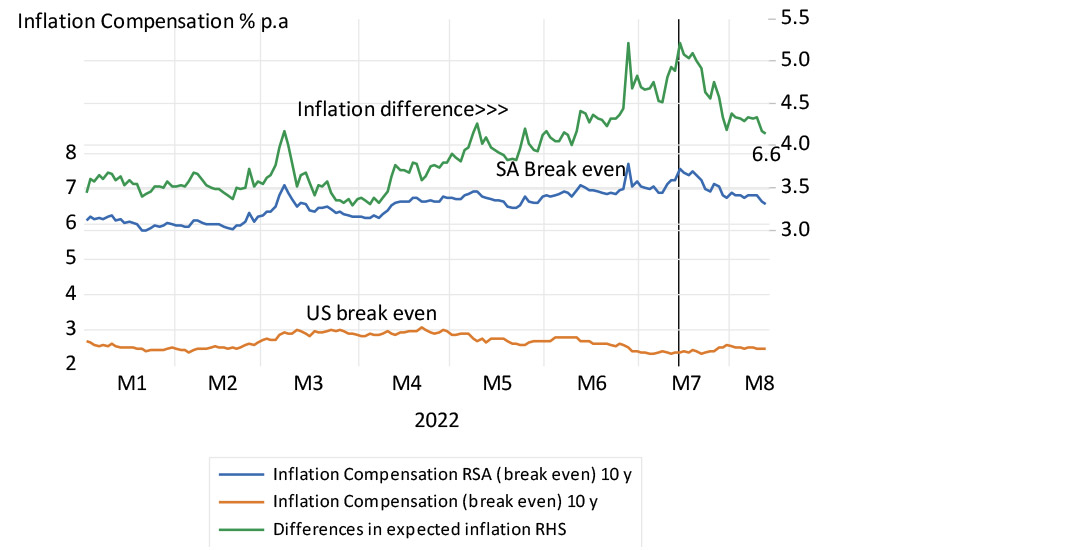

The Reserve Bank is ill advised to react to exchange rate shocks in ways that further threaten the growth outlook – and can prove counterproductive by weakening the rand that then lead to still higher prices. Interest rate increases make sense when excess spending – excess demand – is putting pressure on prices. Which is not the case for the SA economy today. The right response to exchange rate shocks is to ignore them as their temporary impact on the price level falls away. Absent any additional consistent pressure on prices from the demand side of the economy, over which the SARB will always have strong influence. The notion of self-perpetuating inflationary expectations, as promoted by the Reserve Bank when explaining its interest rate reactions to a weaker rand, is supported neither by evidence nor is it consistent with self-interested economic behaviour. It is poor theory and even poorer practice.

But this leaves open the question- why then have interest rates come down in SA? The answer can be found offshore. The Fed has found good reason not to push its own rates higher. The pause on rate increases in the US became widely expected and was confirmed yesterday gives the SARB even less reason to raise its own interest rates. The Fed by dealing effectively with a surge in inflation (which has not been self-perpetuating) has improved the outlook for interest rates, the SA economy and the rand.

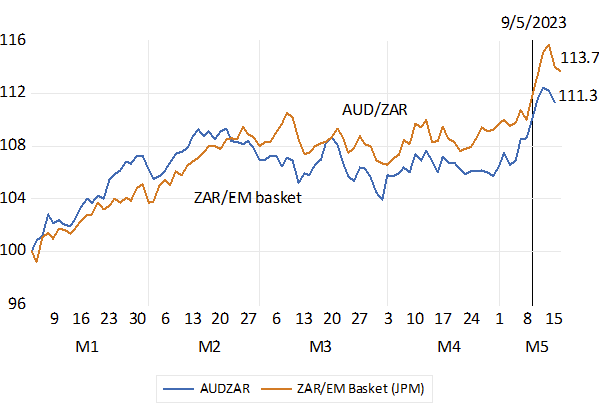

Update on US Inflation – to May 14th 2023.

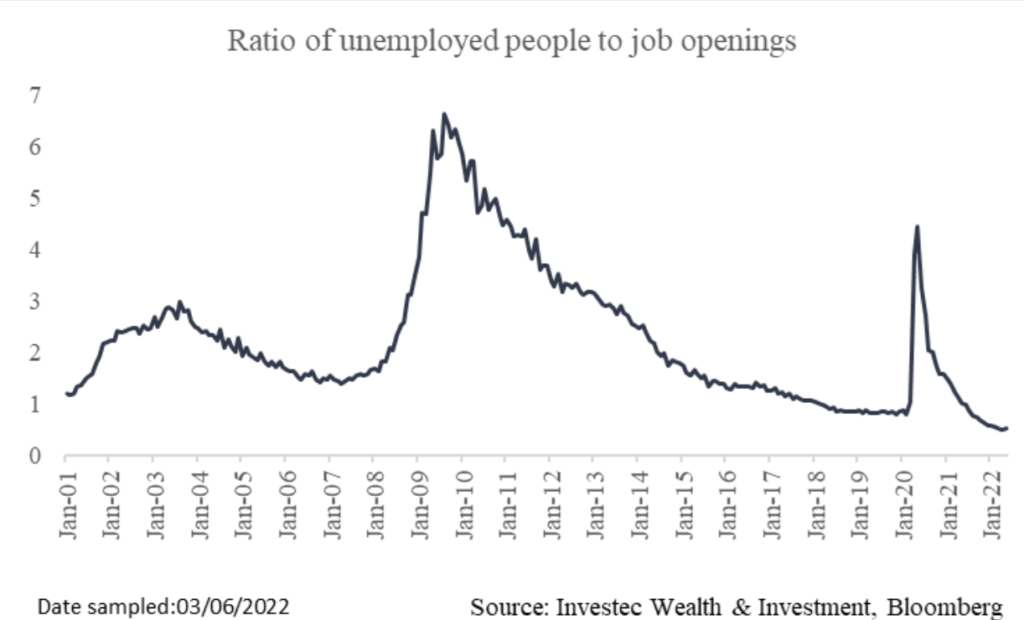

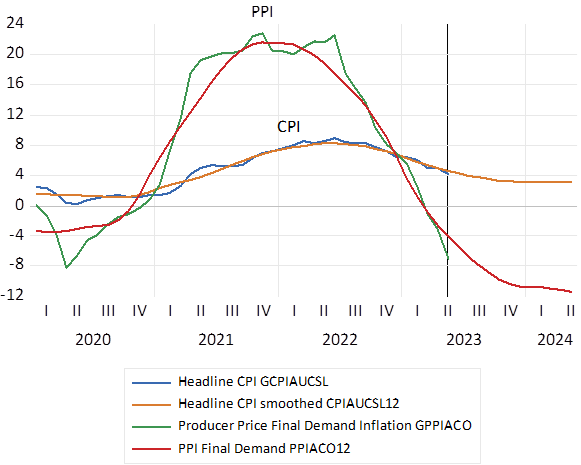

Both CPI (4.0%) and PPI headline inflation fell more than expected in May. Monthly moves were low – 0.2% for CPI and negative for PPI. The only proviso was the elevated rate 0.4% m-m for core CPI- CPI excluding energy and food. But core has a very large rental weight- over 40% which was up 8% y/y – but rentals are clearly heading lower and core may not be the most useful leading indicator for CPI – PPI- now strongly lower may do much better in predicting CPI.

The Fed paused but member dot plots indicated further increases to come. But the Chairman says the Fed will remain data dependent and my view is that the Fed panic about inflation is over. Because demand pressures on inflation are largely absent- thanks to higher interest rates and negative growth in money supply and bank credit. The global pressure on interest rates in SA is therefore abating. As discussed in my commentary above

US Headline Inflation Y/Y growth in Index

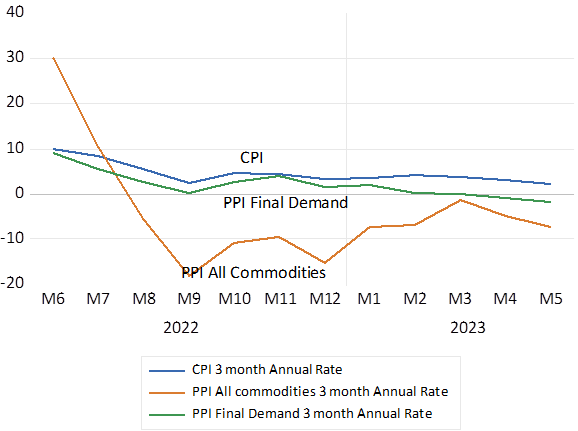

US Inflation over the past three months – % per 3 months annualized. CPI now running at a quarterly rate of 2%. PPI inflation – headline and quarterly- is now negative

Monthly % move in CPI Seasonally Adjusted. Latest April-May 2023=0.12%.