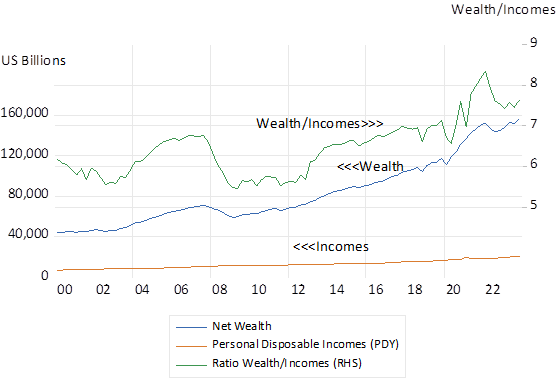

You are only wealthy if you have saved a good proportion of your income over the years and not consumed it all, to sustain an extravagant lifestyle. It is however your wealth that makes your large incomes and consumption tolerated by the wider society. Thus making it possible for the talented and diligent and hard-working and, most important for a growing economy, the enterprising and innovative successful risk takers, to earn their high incomes legitimately and enjoy their consumption and also help create their most useful wealth.

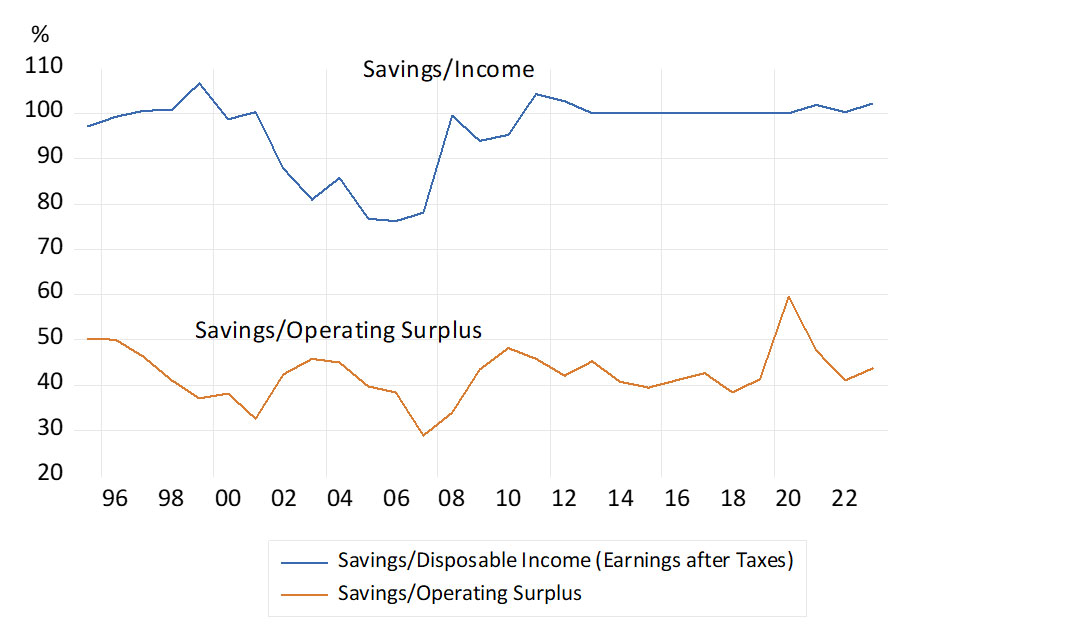

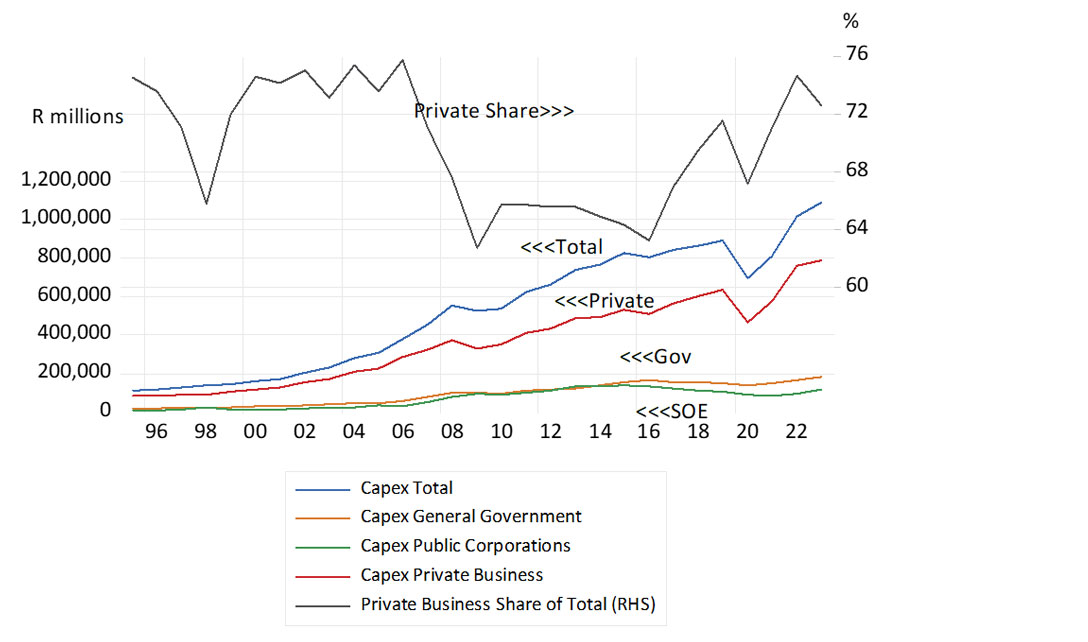

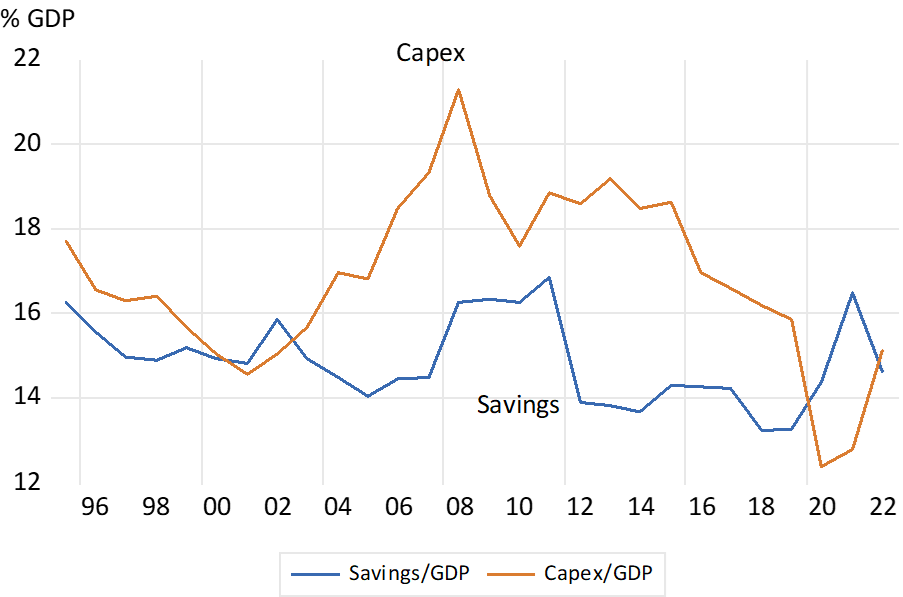

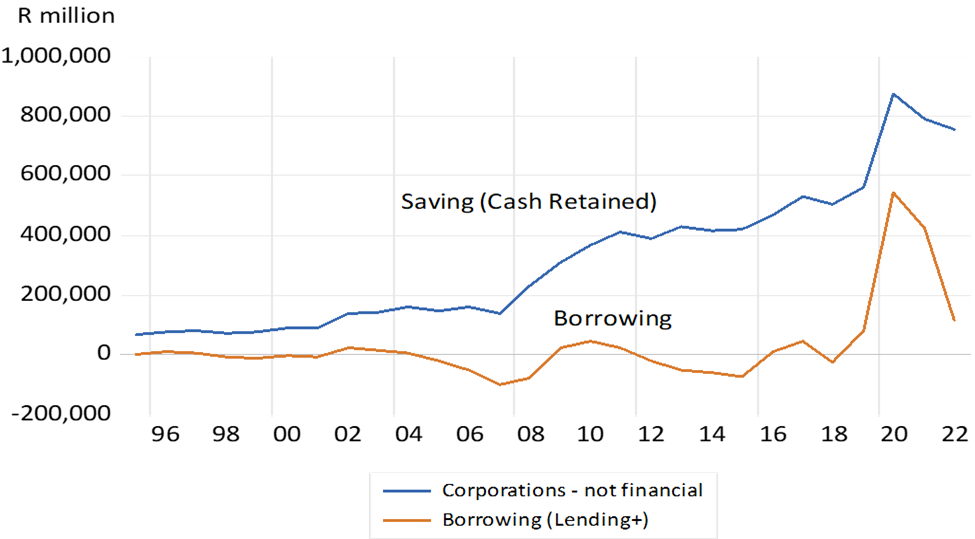

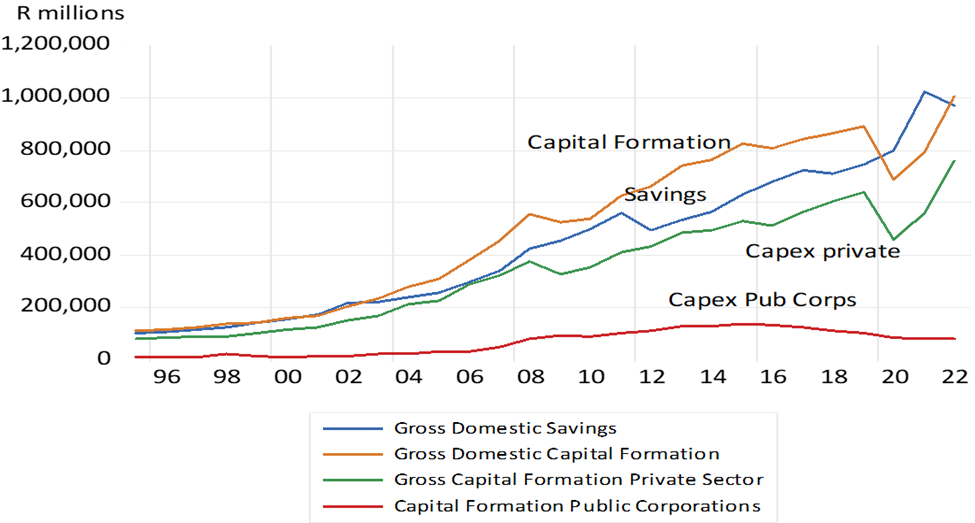

The savings that add to wealth and most important are invested productively by the income seeking business organisation that also saves and borrows and undertakes capex on behalf of their owners. These firms are given the responsibility to manage the capital stock and all the complementary scarce resources that are entrusted to them. Including employing workers and managers whose wages and rewards will depend on the good returns on capital (savings) their employers are able to realise to sustain their enterprise.

The more such capital is created and made available to the economy in the form of plant, equipment, dams, roads and ports etc and the more efficiently they are managed, the higher will be the incomes earned by the poorer households. More capital raises the relative scarcity of labour and improves productivity and incomes. Which makes the people understandably willing to protect the wealth that funds real assets against damage or theft or violent expropriation by local or foreign invaders. The protection and respect for property, that is for capital or wealth, in turn encourages the potentially higher income earners to venture more, to earn more and to save and invest more in the capital stock. Thus serving the essential interests of the wider community.

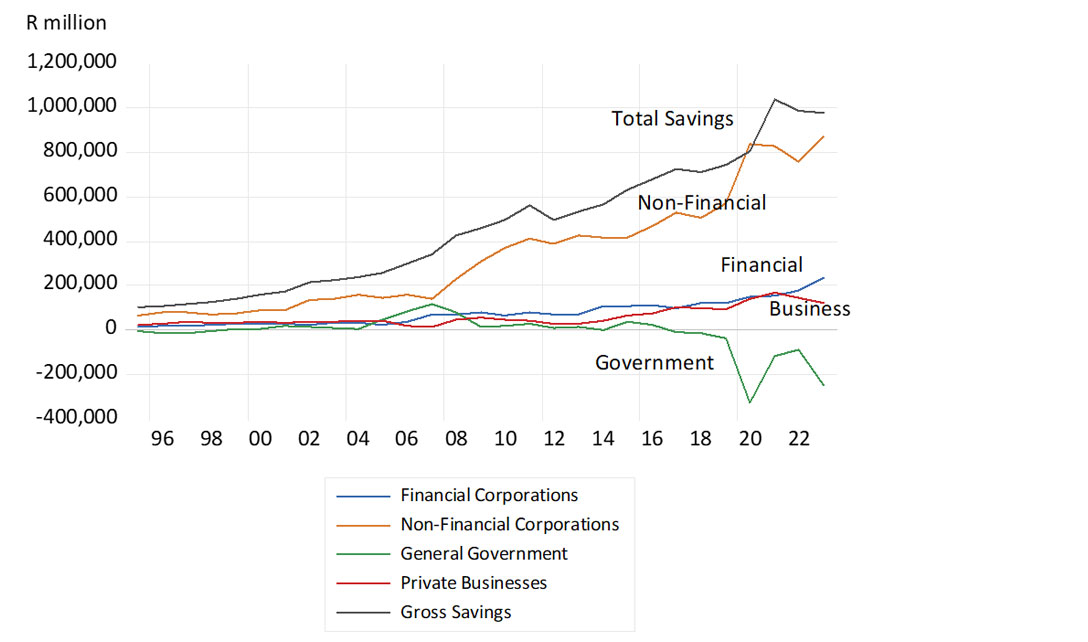

The consumption of others is not helpful to you- it adds to the competition for scarce resources. Saving, accumulating wealth to fund an investment in real assets is very helpful for the many without much wealth. It is the large-scale waste of capital, extracted by taxes, as has been the case with our SOE’s, that should be condemned.

Such essential willingness to protect property is to be found in the Bible and the rabbinical commentaries on it. As I was pleased to discover at a recent joyous barmitzvah. The substance of the readings that day were the laws and regulations governing the protection of property and compensation for its damage, intentional or accidental. And about laws that also regulated the rights and obligations to an important asset class of those times, the slave. All food for my economist soul.

There was little more I could read that morning about the creation and purpose of wealth. I thought I would ask this question of the Torah and Rabbinical commentary, the Talmud using AI. Rab AI so to speak. Here is a summary of the responses received, with my reactions indicated between brackets.

“The Talmud places a strong emphasis on the importance of hard work and diligence. It acknowledges that while effort and work are important, ultimately, one’s success may also depend on divine blessing. (Unbelievers will call this luck) The Talmud establishes the principle that those who are wealthy have a responsibility to support the less fortunate. The act of giving is seen as a valuable pursuit, and generosity is highly praised. Wealth is viewed as a trust that comes with significant responsibilities – that one should use their wealth not just for personal pleasure but also for the betterment of society. This includes supporting community needs and contributing to public welfare. (My point about the social purpose of wealth being the creation and preservation of the productive capital stock for the benefit of the greater society, has not apparently been recognised)

The Talmud warns against excessive attachment to wealth. A person should not let the pursuit of wealth dominate their life to the detriment of their spiritual and ethical responsibilities, that through work and the creation of wealth, one can achieve personal and communal fulfilment.”

(Ancient wisdom that is clearly consistent with human aspiration and economic development that implicitly recognises inevitable differences in economic outcomes as socially helpful)