The Hard Number Index points lower

There is little comfort to be found about the current state of the SA economy in our Hard Number Index (HNI) for the SA business cycle that has been updated to July 2009. The HNI declined further from 129.48 in June to the current reading of 127.07 (2000=100). The direction of the index, its rate of change or the second derivative of the business cycle, suggest that the time when the rate of decline starts to level off is at hand though the prospects of positive growth seems some way off.

No pick up in vehicle sales or growth in the supply of cash

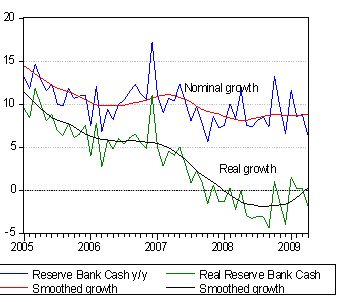

The HNI is an equally weighted combination of two very up to date indicators: vehicle sales; and the notes issued by the Reserve Bank, adjusted for consumer prices to provide a measure of the real money base. Both indicators are hard numbers, rather than based on sample surveys, and they are updated to the July month end. Neither series is showing improvement. The growth in the supply of cash to the system continues to slow marginally while new vehicle sales remain well below year ago levels and this deeply negative rate of growth (-40%) has not yet become obviously less negative.

The consolation to be found is in the influence of less inflation on the real supply of cash. The real money base is trending to barely positive growth.

Relief urgently called for

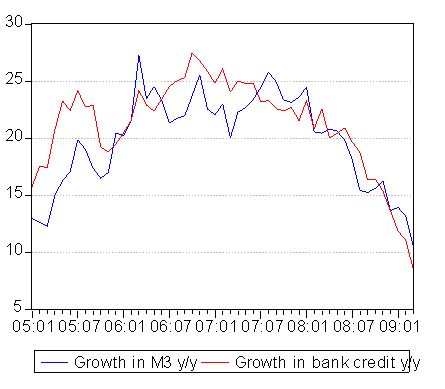

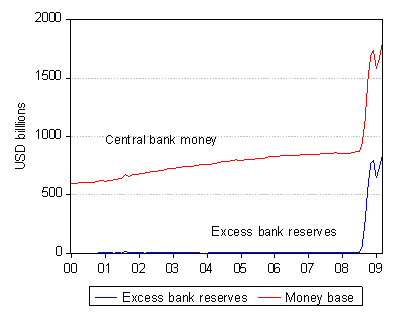

This data would ordinarily make it ever more obvious that the SA economy derives all the help it could get from easier monetary policy. Lower interest rates, combined with quantitative easing, both of which are active steps designed to increase the supply of cash to the banks (who are proving so reluctant to lend) are even more urgent now than they were six months ago.

The reluctance of the Reserve Bank to do what almost every other central bank has been doing to ease the pain of recession has been very difficult to appreciate. We have explained why the Bank’s concern for inflationary expectations is not sensible in these unhappy circumstances when the gap between actual and potential output of the SA economy has widened so damagingly and when prices at the factory farm and port gates as measured by the Producer Price Index (PPI), are falling so sharply. We argued that inflationary expectations were rising because it had become apparent that a change in Reserve Bank leadership was inevitable given its lack of flexibility and that more inflation tolerant policies might be adopted.

Plus ça change?

The change in leadership to come has since occurred with the prospect that low inflation over the long run will remain a primary concern of the Reserve Bank. However hopefully not regardless of the state of the economy and with attention focused only on consumer prices, which are particularly insensitive to the state of demand in the economy over which the Bank exercises its influence.

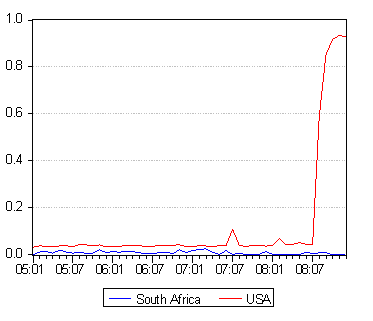

Less inflation now expected

Inflation compensation offered in the RSA bond market, being the difference in yields on offer between conventional bonds and their inflation linked equivalents have moderated recently. This is the most objective measure of inflation expected. Another measure of inflation to come is the expected direction of the rand over the long run. The difference in RSA and USA long bond yields indicates break even rand depreciation expected. That is in equilibrium the differences in nominal yields will be expected to be eliminated by a weaker rand. Thus the wider the difference in such bond yields the more rand weakness expected and so the more SA inflation on average will be expected to exceed average inflation in the US over the long run. This measure is also indicating less weakness for the rand now expected over the long run.

Ever more reason for easier monetary policy – will reason prevail?

There is therefore even more reason for lower short term interest rates in SA now than there was in June 2009. The economy has weakened further, pricing power of producers is clearly suffering further and the administered price dominated and recalibrated CPI is also rising at a slower rate than it did earlier in the year. Furthermore inflation priced into bond yields is now less than it was.

Can even the Reserve Bank with its lame duck leadership resist this evidence? We think not and expect a (surprising to the market) 50bp cut in the repo rate.

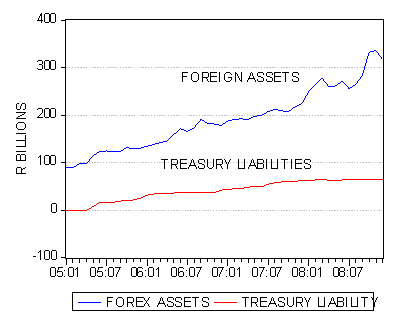

Source; Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis and Investec Securities

Source; Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis and Investec Securities