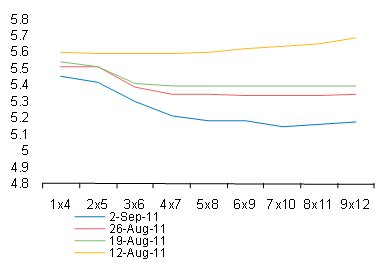

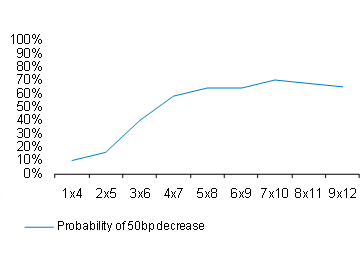

The MPC yesterday downplayed the risks to inflation correctly, while the risks to the domestic economy received full attention. Listening to the litany of economic problems facing the SA economy referred to by Governor Gill Marcus during her speech (quoted below*) I had a moment of near exhilaration that the MPC would in fact surprise the market by cutting rates. The economy is clearly screaming out for them as it has been doing for some time.

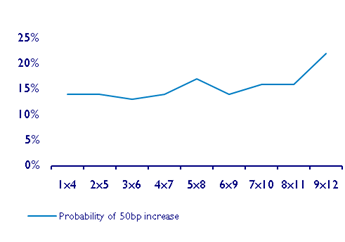

But then caution prevailed. We can blame global risk aversion and its impact on the rand for the predictable pusillanimity in Pretoria. But the case for an interest rate cut was debated and the Governor provided every indication that a cut next time round is now very much more likely (if the economy stays on its present sub-optimal course) and especially if the rand recovers some of its losses, which it will if the global risk appetite recovers to a degree. Brian Kantor

Extracts from the MPC statement that pointed to interest rate action, not inaction:

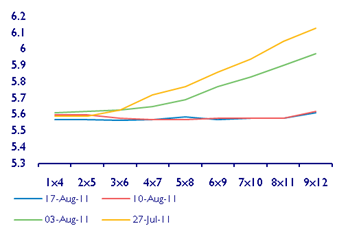

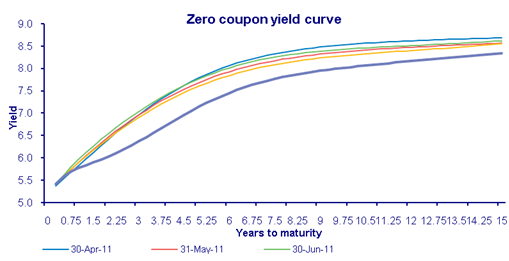

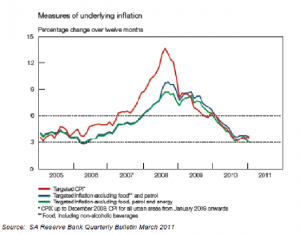

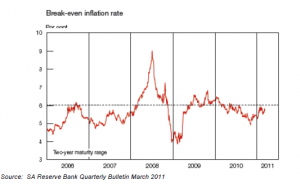

The depreciation of the rand poses a potential upside risk to the inflation outlook. However the degree of this risk will depend on the extent and persistence of the depreciation trend, which in turn will be influenced by the duration and intensity of global risk aversion. The rand tends to be more sensitive to changes in global risk perceptions than most of its emerging market peers. At this stage the MPC still considers the upside risk to the inflation outlook from this source to be relatively moderate, but rising.

Domestic economic growth remains disappointing, with the negative output gap widening to around 3 per cent in the second quarter of 2011 and gross domestic product growing by 1,3 per cent, following the 4,5 per cent increase recorded in the first quarter. Both the primary and secondary sectors contracted in the second quarter, while real value added by the tertiary sector increased only marginally. Wide-spread industrial action, which continued into the third quarter, contributed to this subdued outcome, and is expected to weigh negatively on third quarter prospects as well.

Recent high frequency indicators are also not very favourable. Mining production contracted at a year-on-year rate of 5,1 per cent in July, and by 4,3 per cent on a month-on-month basis. Manufacturing output declined at a month-on-month and year-on-year rate of 6,0 per cent in July, confirming the sharp decline to 44,2 index points observed in the Kagiso/BER Purchasing Managers Index (PMI) in July. Despite a modest recovery in August to 46,7 index points, the PMI remained below the neutral 50 level, pointing to a further possible contraction in the sector. The construction sector also remains subdued with both the FNB Building Confidence Index and the FNB Civil Construction Index remaining at very low levels, while there was a further decline in the number of building plans passed in the third quarter.

Overall business confidence, as reflected in the RMB/BER Business Confidence Index, has declined for two consecutive quarters, and at 39 index points is well below the neutral level of 50. The Bank has lowered its forecast for average growth in 2011 to 3,2 per cent, down from 3,7 per cent, while the forecast for 2012 has been reduced from 3,9 per cent to 3,6 per cent. The forecast for 2013 remains unchanged at 4,4 per cent. The lower forecast is a result of the lower-than-expected outcome in the second quarter, as well as a downward adjustment to the global growth assumption. The risks to this outlook are seen to be on the downside.

The lower growth trajectory does not bode well for employment creation, which has been relatively muted. According to Statistics South Africa, employment in the formal non-agricultural business sector increased by 0,1 per cent or 5,701 people in this second quarter of 2011. The outcome was, however, negatively affected by the decline in public sector employment associated with the termination of contracts of temporary employees hired for the municipal elections.

Consistent with the moderation in domestic production, growth in real gross domestic expenditure also declined, from an annualised growth rate of 7,9 per cent in the first quarter of 2011, to 1,3 per cent in the second quarter. A positive development was the further acceleration in the growth of real gross fixed capital formation, albeit off a low base, from an annualised rate of 2,7 per cent in the first quarter to 4,0 per cent in the second quarter. Nevertheless the ratio of gross fixed capital formation to GDP, at 18,9 per cent, is still well below the peak of 24,6 per cent measured in the fourth quarter of 2008.

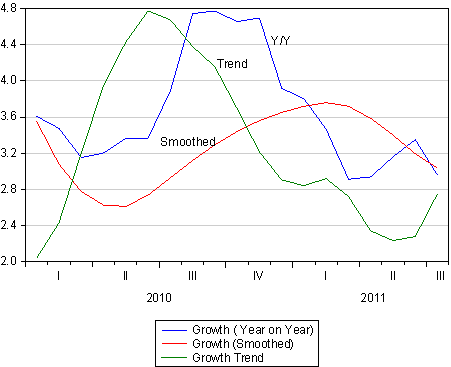

Consumption expenditure by households has to date been the main driver of growth. However, in the second quarter of 2011, growth in consumption expenditure moderated to an annualised rate of 3,8 per cent, compared with an increase of 5,2 per cent in the first quarter. Real retail trade sales increased at a year-on-year rate of 2,8 per cent in July, but declined by 0,7 per cent in the three months to July compared with the previous three months. Growth in motor vehicle sales, while still positive, has also declined. Consumption patterns may have been distorted somewhat by the high base effects arising from the 2010 World Cup, and a clearer picture should emerge in August. The RMB/BER Consumer Confidence Index has declined for two consecutive quarters, underlying the fragility of the outlook.

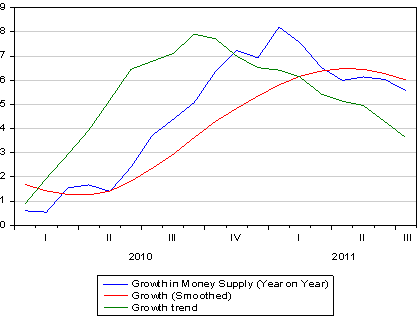

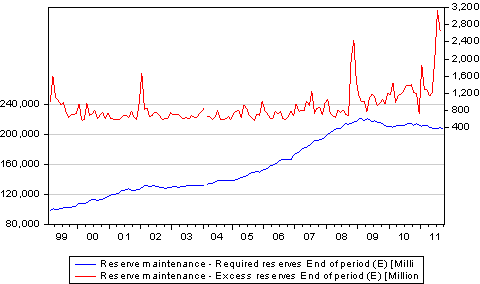

Consumption expenditure is expected to remain constrained to some extent by low rates of credit extension and continued debt deleveraging by households. The ratio of household debt to disposable income declined further to 75,9 per cent in the second quarter of 2011 from a peak of 82,0 per cent in the first two quarters of 2008. Twelve-month growth in total loans and advances extended by banks to the private sector has fluctuated around 6 per cent in the three months to July. Mortgage advances, which is the largest category of credit, grew at a year-on-year rate of 2,9 per cent, consistent with the slow pace of recovery in the domestic property market. The main driver of growth in credit extension was the category of other loans and advances, in particular general loans which reflect primarily corporate sector borrowing. This category grew by almost 15 per cent in the year to end of July.

Source: MPC statement, 22 September