The first and second meetings of the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) of the Reserve Bank in 2014 have come and gone and been accompanied by very different reactions in the money market.

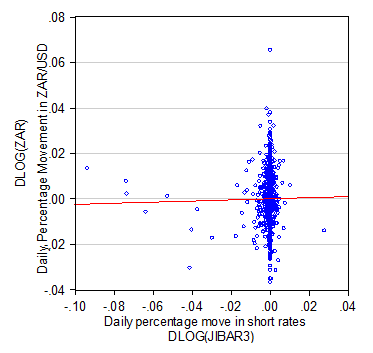

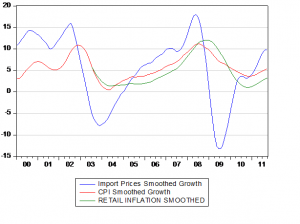

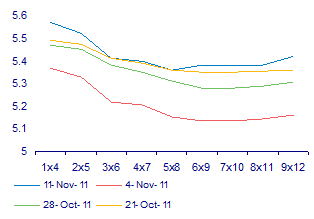

The first meeting on 29 January produced a significant interest rate surprise on the upside when the MPC decided to raise its key repo rate by 50bps. The second meeting on 27 March produced a much smaller surprise in the other direction. Note in the chart below that the first upside interest rate surprise in January 2014 was associated with a significantly weaker rand while the surprising downside move in short term interest rates in March was accompanied by a stronger rand. Short term rates are represented in the figure by the Johannesburg interbank rate (Jibar) expected in three months – that is the forward rate of interest implicit in the relationship between the three month and six month JIBAR rate. Changes in this rate indicate interest rate surprises. Hence the inflation outlook deteriorated as interest rates moved higher and improved as interest rates were kept on hold.

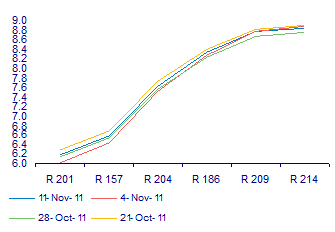

This inconsistent and essentially unpredictable relationship between movements in SA interest rates and the rand is clearly coincidental – it is not a causal relationship because the value of the rand is determined by global or (more particularly) emerging market economic forces rather than domestic policy decisions. As we show below, where emerging market equities go, the rand follows. And emerging equity and bond markets are led by global risk appetite. The more inclined global investors are to take on more risk, the better emerging market equities and bonds perform, including those listed on the JSE. The behaviour of SA stocks and bonds and the exchange value of the rand is highly consistent with that of emerging markets genrally as we show in the chart below. The rand follows the Emerging Market Equity Index (MSCI EM) as does the JSE All Share Index (both in US dollars) while both the rand and the JSE respond to the spread between RSA and US Treasury 10 year bond yields that can be regarded as a measure of SA specific exchange rate risk. The wider the spread the more exchange rate weakness expected.

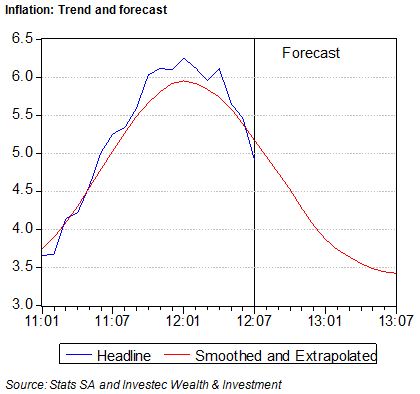

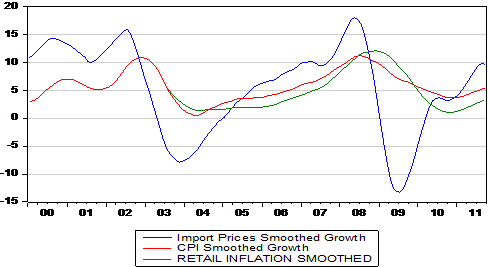

And so the Reserve Bank remains essentially powerless to manage inflation in the face of exchange rate shocks (over which it has no obvious or predictable influence). Interest rates can influence spending in SA, causing the economy to grow faster or slower without necessarily influencing the direction of prices. In other words inflation can rise, as it has done recently, even though the economy has operated well below its potential and will continue to do so. Therefore higher interest rates can slow the economy down further without causing inflation to fall. This is a painful dilemma of which the MPC seems only too well aware. To quote its statement of 27 March:

“The Monetary Policy Committee is acutely aware of the policy dilemma of rising inflation pressures in a subdued economic growth environment.

“The main upside risk to the forecast continues to come from the exchange rate, which, despite the recent relative stability, remains vulnerable to global rebalancing. The expected normalisation of monetary policy in advanced economies is unlikely to be linear or smooth, and the timing and pace is uncertain.

“The rand is also vulnerable to domestic idiosyncratic factors, including protracted work stoppages, electricity supply constraints, and the slow adjustment of the current account deficit. Pass-through from the exchange rate to prices has been relatively muted to date but there is some evidence that it is accelerating. However, the forecast already incorporates a higher pass-through than has been experienced up to now.

“At the same time, the domestic economic outlook remains fragile, with the risks assessed to be on the downside. Demand pressures remain benign as consumption expenditure continues to slow amid weakening credit extension to households and high levels of household indebtedness. The upward trend in the core inflation forecast is assessed to reflect exchange rate pressures rather than underlying demand pressures.”

So then how should the MPC respond to exchange rate-driven price increases? The obvious answer would appear to be to accept the limitations of inflation targeting in the absence of any predictable reaction of exchange rates to interest rate settings. That is to ignore completely the exchange rate shock effect on inflation and focus on domestic forces that influence the inflation rate: lowering rates when the economy is operating below potential and raising them when spending (led by money and credit growth) is growing so rapidly as to add to inflationary pressures. And to explain very clearly why it would be acting this way.

But this unfortunately is not the way the MPC is still inclined to think. It worries about the inflationary effect of inflationary expectations. To quote its recent statement again:

“Given the lags with which monetary policy operates, the MPC will continue to focus on the medium term inflation trajectory. The committee is aware that too slow a pace of tightening could undermine inflation expectations and may require more aggressive tightening in the future. Consistent with our mandate, a fine balance is required to ensure that inflation is contained while minimising the cost to output”.

The MPC would be well advised to accept another bit of SA economic reality, which is that not only does the exchange rate lead inflation, but inflation itself leads inflation expectations – not the other other way round. There is no evidence that inflationary expectations lead inflation higher or lower. More SA inflation leads to more inflation expected though, as the MPC is well aware, inflation expected has remained remarkably constant over the years: around six per cent per annum that is the upper end of the inflation target band.

The MPC did the right thing this time round not to raise its repo rate. It made a mistake to raise its repo rate at the January meeting. The money market made the mistake of immediately anticipating a further 200bp increase in interest rates by January 2015. The Governor has done very good work guiding the market away from such interest rate expectations that, if realised, would be even more costly to the economy. The money market now expects only a 100bp increase in short term rates by early next year. The market may again be very wrong about this, dependent as the direction of inflation and interest rates are on the behaviour of the rand over the next 12 months. But even good news for the exchange rate will still leave monetary policy in SA on a fundamentally wrong tack. The interest rate cycle in SA, as in any normal economic state of affairs, should be led by the state of the domestic economy, not by the direction of unpredictable global capital.