[The text has been revised to correct an earlier version that failed to recognise the sharp reduction in interest rates after the Global Financial Crisis]

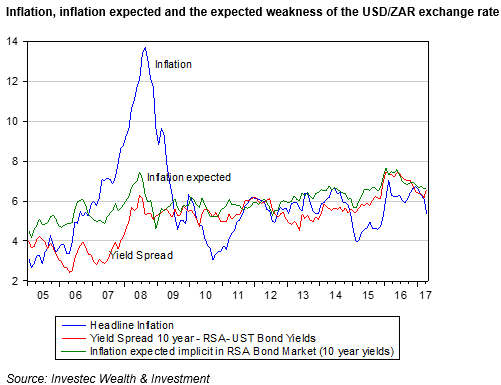

The Reserve Bank kept interest rates on hold in May because, as it explained, there were upside risks to the exchange rate. The risk was that if the rand weakened significantly it might have called for an immediate reversal of any interest rate reductions. Since then the Bank has provided further helpful detail of how its Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) goes about its risk adjusted exchange rate forecasting. We quote extensively from a recent address by Brian Kahn, Advisor to the Governor. [1]

To quote Mr.Kahn:

“How do we deal with the exchange rate in our (inflation) forecast? We make a simplifying assumption of a stable real effective exchange rate over the forecast period. That implies an expectation of a rand depreciation over that period in line with inflation differentials with our major trading partners. We then use our judgement to assign a risk to this assumption, which then feeds in to the overall risk to the inflation forecast…”

And to quote further

“….It is not just the forecast itself that is of importance, but also how we perceive the risks to the forecast. Any particular forecast trajectory could have a different policy outcome depending on how we assess the risks. MPC members may have differing views of these risks, which explains to some extent why we do not always have unanimity in the decision-making process…”

And on the forecasting method itself Mr Kahn explained

“…The critical issue then is the level of the starting point. As a general rule, we set it at the prevailing index level of the real exchange rate. However, if we feel that the exchange rate is clearly over- or undervalued at that point, we may adjust that level. In other words, should we regard the current strengthening or weakening of the rand as being temporary, we may not adjust the assumption fully until we have greater confidence of its persistence at those levels. The level that we choose has an important implication for the forecast. In 2016, for example, we saw a progressive improvement of the inflation forecast over the year. Most of this was due to revisions to the exchange rate assumption, following a recovery of the rand ……”

Mr Kahn made it clear that

“…While the exchange rate is one of the important variables in our inflation forecast, it is not the only one and we have to look at its impact in conjunction with the movement of other variables. And we certainly do not conduct monetary policy with a view to impacting on the rand itself…”

Forecasting the ZAR is easier said than done. In reality it is an impossible task to fulfil with any degree of confidence. If past performance of the USD/ZAR is anything to go by the chances of the rand going up or down is statistically about the same. This is not surprising given the size of the market in the ZAR and the advantages an accurate forecast would offer any professional currency trader. In practice all that might be known by professional traders about what might determine the value of the ZAR in the future, will already have been incorporated in the current price of a US dollar. And so the exchange rate moves randomly from day to day, or minute to minute, as more information about the forces that influence the exchange rate are continuously revised.

Daily percentage moves in the USD/ZAR since 2006 and June 2017 have averaged very close to zero, .000230% per day to be exact. The worse day for the ZAR over this period was a 16% fall on the 15th October 2008 during the height of the Global Financial Crisis and the best a 7.5% gain registered on the 28th of that fateful October 2008. Monthly moves in the ZAR are also a random walk with a weaker long term bias. On average since January 1995, the USD/ZAR has declined by 0.59 per cent per month, the worst month being October 2008 when the ZAR lost 20% of its value and the best month was April 2009 when the rand gained over 11% against the USD (See below)

The real rand exchange rate – that is the value of the rand adjusted for differences in inflation between SA and its trading partners – indicates some tendency to revert to its Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) value over an extended period of time. Or in other words faster inflation that follows a weaker ZAR helps to strengthen the real rand given enough time. Given also some stability in or absolute strength in the nominal ZAR. On these grounds and given the recent level of the real rand this might have led the MPC in a less rather than more risk reverse direction. But on a day to day, or even year to year basis, the value of the real rand will be dominated by much wider movements in the nominal, that is the market determined, exchange rates, rather than by differences in more stable inflation rates. An exchange rate that as we have pointed out that fluctuates randomly and so for which the best estimate of tomorrow’s price of a USD value is today’s rate.

In figure 3 below we show how the USD/ZAR exchange rate has deviated from its PPP equivalent value since 1970. Exchange rate shocks- when the exchange rate moved sharply away from its PPP value can be identified in 1985, 1998, 2001, 2008 and also 2011. Though between 2011 and mid 2016 the real rand was subject to an extended period of growing weakness. This was a period of persistent USD strength and weakness of most other Emerging Market currencies.

As may be seen the USD/ZAR has been persistently weaker than would be predicted by the ratio of the Consumer Price Indexes in the two economies since 1995. In 1995 the SA economy was permanently opened to capital flows that had been tightly controlled before – with a brief interlude of freedom from capital controls for foreign investors between 1983 and 1986. It is of interest to note that when capital flows to and from SA were tightly controlled, the exchange rate, conformed very closely to PPP- truly levelling the trading field for importers and local producers competing with them. This currency, used for foreign trade purposes, was known as the Commercial Rand to distinguish it from the consistently less valuable Financial Rand used for transactions of capital undertaken by foreign investors in SA. After 1995, variable flows of capital to and from SA have come to dominate movements in the market determined unified ZAR exchange rates. Any assumption that these exchange rates would conform to PPP would not be a realistic one given the record of exchange rates since 1995- as shown in figure 3 and 4.

This real weakness was largest in percentage terms in 2001 and the real rand was again very weak in 2016. (See figure 3 below) The real trade weighted rand, as calculated by the Reserve Bank, varies about 100 to conform to PPP, as it was assumed to do in 2010. Real strength is represented by increases in the real exchange rate. The real trade weighted rand is compared with the real ZAR/USD exchange rate that uses the respective CPI Indexes In figure 4. The figure indicates a very strong real USD/ZAR exchange rate in the late seventies and early eighties when the USD itself was very weak on its own trade weighted basis. The real trade weighted ZAR rate has a current value of 89 compared to a less valuable 83 for the real USD/ZAR exchange rate.

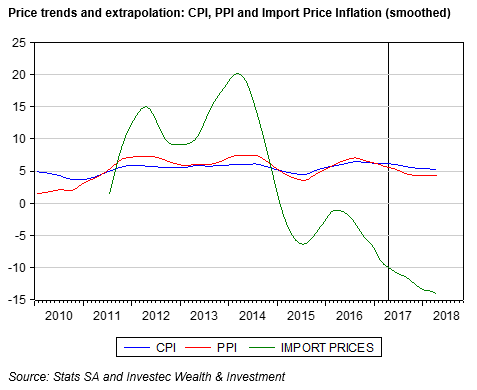

As Mr.Kahn has explained the exchange rate has a very important influence on the SA inflation rate in SA given the openness of the SA economy to imports and exports- that together amount to over 50% of the GDP. Ideally from the perspective of monetary policy and appropriate interest rate settings, the ZAR exchange rate would be well behaved. Well behaved in the sense that exchange rate trends would closely follow domestic inflation and help maintain the level trading field when exchange rates largely compensate for differences in inflation – that is PPP more or less holds. That is movements in exchange rates compensate for differences in inflation rates between trading partners to neither add to or subtract from the competitiveness of local suppliers in either the local or foreign markets. If so the price of a dollar (and so the rand value of exports or imports) would be determined by the same forces that simultaneously determine the prices of all the goods and services that make up the CPI. In which case prices might rise faster or slower and the exchange rate would depreciate in line. When demand exceeds supply prices, including the rand price of a USD would tend to rise faster – and vice versa. Too much demand and the inflation and exchange rate weakness associated with it would obviously call for higher interest rates. And too little demand- associated with low rates of inflation and a stronger rand would call unequivocally for lower interest rates.

But unfortunately for SA the ZAR exchange rate is not well behaved. It often takes an unpredictable course set quite independently of the forces of demand and supply in the economy. Inflation – depending on the exchange rate and other forces- then follows more or less closely the independent direction of the exchange rate. And interest rates in SA then follow inflation, usually higher sometimes lower, regardless of the causes of inflation and the prevailing state of the economy. They therefore may rise even though domestic spending is growing ever more slowly- as they have done in SA since 2014. These higher interest rates in turn help depress spending further that is already under pressure of higher prices. These forces are known in the economics literature as supply side shocks to prices- less supply means higher prices – as they would in a drought that reduces supplies to the market place and raises price. And supply side shocks, according to the same literature, are considered to be reversible with temporary not permanent effects on inflation- and not to call for monetary policy responses

As Mr.Kahn has explained the current weakness of demand in SA makes it harder for firms to pass on higher costs to their customers- so reducing inflationary pressures to a degree- but simultaneously making it all the more difficult for the firms to invest more or hire more workers. This repression of domestic demand has added to the other recessionary forces under way. Without having any predictable influence on the exchange value of the rand – which as Mr.Kahn has also indicated, is anyway not a target for monetary policy.

The sooner the Reserve Banks lowers interest rates the better the chance of the economy recovering from recession. Delaying the interest rate reductions for fear of what might happen to the exchange rate prolongs rather than relieves the economy agony. There is surely much more at stake than forecasting the exchange rate accurately- a task surely well beyond the capabilities of the MPC or indeed any other forecaster.

There is an obvious way out of this dilemma – of having to increase interest rates to fight inflation, when interest rates have had nothing to do with the exchange rate and the inflation under way. And higher interest rates can only slightly inhibit inflation by further depressing spending that is already depressed. The alternative is for the policy makers to treat exchange rate shocks to inflation as what they surely are – a temporary supply side shocks that will increase prices perhaps for a year and then fall out of the CPI, off a higher base level.

The narrative that suggests all inflation- whatever its cause- demand or supply side – needs to be met with higher interest rates needs to be a very different one. Not raising rates in the face of a supply side shock should moreover not be allowed to indicate any tolerance for higher inflation rates over the longer run. But it would be a narrative that would not allow inevitably risky exchange rate forecasts to influence interest rate settings that induce recessions. Monetary policy should allow a volatile exchange rate to help absorb the pressure of more adverse economic circumstances, not to exacerbate them

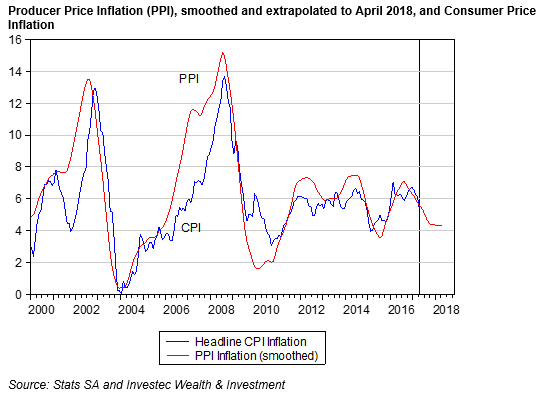

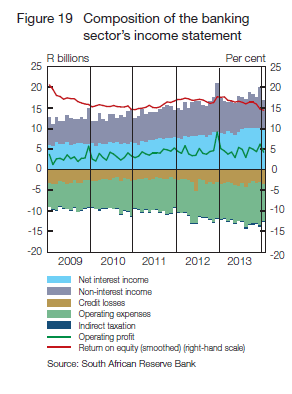

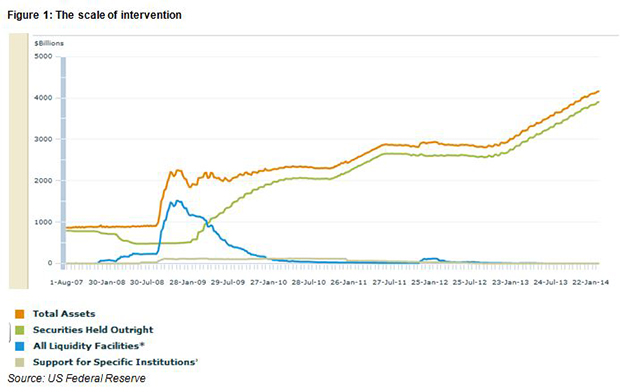

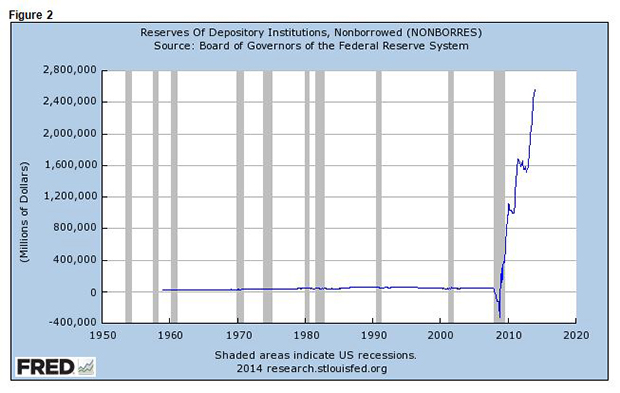

South Africa has a very poor record managing exchange rate shocks. The response to the emerging market shock to the ZAR in 1998 was one such particularly disastrous example. The interest rate increases that followed the 2001 exchange rate collapse was also not an appropriate response. Interest rate increases that were then sharply reversed after 2004 when the ZAR recovered and the economy picked up boom like momentum. A less severe hiking of interest rates prior to the 2008 Global Financial Crises, that was accompanied by ZAR weakness might have served the economy better. Though when the rand strengthened markedly soon after the crisis interest rates were lowered very sharply by as much as 7%. This undoubtedly helped the economy overcome a brief recession. Furthermore would inflation been any higher had interest rates not been increased after 2014 – in response to rand weakness and higher inflation and the recession perhaps avoided? (See figure 5 below)2

Had these exchange rate shocks to inflation been ignored, it can be strongly argued that SA inflation over the longer run would not have been very different and that growth rates would have been on average higher and less variable. The logic of inflation targeting – in the presence of un-predictable exchange rates that do not conform to purchasing power parity – needs to be seriously re-considered. The impaired logic of inflation targeting in SA can surely be reassessed without appearing soft on inflation.

Given that any immediate change in monetary policy philosophy is unlikely the improved outlook for inflation is such and further improved by recent stability in the ZAR- that lower interest rates will follow at the next MPC meeting in July 2017. The pace of further declines in the repo rate will follow inflation lower. The chances of a cyclical recovery in the economy depend crucially on lower short term interest rates – the sooner they come and the steeper the reductions the better.

1 “Check in” from the South African Reserve Bank

Address by Brian Kahn, adviser to the Governor,

to the 6th Annual Nedgroup Investments Treasurer’s Conference,

Summer Place, Hyde Park, 8 June 2017; www.resbank.co.za