A Business Day leader (29 June) referring to the more than doubling of Eskom’s reported profits in 2010-11 to R8.5bn raised the question of whether the electricity utility should have been granted the large increases it was.

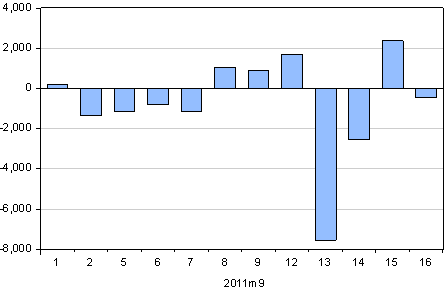

Reference in this regard might have been better made to the cash flow generated by Eskom’s operations. These amounted to the very substantial flow of R28.3bn, representing an increase of R12.3bn or 77% from the year before.

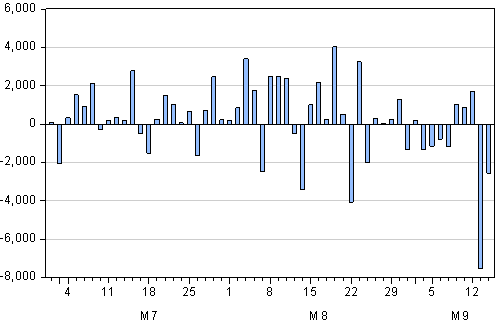

However the net cash flow generated for the company was reduced to R22.3bn, after accounting for the cash lost through so called embedded derivatives (that is the cash cost of meeting Eskom’s contractual obligations to the aluminium smelters) and cash lost and gained from Eskom’s considerable trading activity in financial assets and liabilities, that is in its own debt. The equivalent net cash flow number the year before was a mere R9.1bn, making for an even larger percentage increase of 245% in internally generated cash flow in 2010-2011.

Most impressive of all in pure financial terms is that this R22bn went a long way, more than half the way, to funding the very large R44.3bn of capital expenditure incurred in 2010-2011. In other words, current consumers are now financing more than half of the very large capital expenditure being incurred by Eskom to meet future demands for electricity (for which future consumers will be expected to pay an appropriate price). Next year, after a further 25% increase in its regulated tariff, the revenues and cash flows and the contribution of internal funding can be expected to increase by similar large proportions and amounts.

These financial outcomes should not have come as a surprise to anyone familiar with Eskom’s established generating and distribution capacity.

Once Eskom ran out of its excess supplies of generating capacity and new capacity had to be installed, it became essential to adjust tariffs from those based on historical costs to charges based on the returns required to justify the essential investment in additional generating and distribution capacity. This would inevitably mean large increases in revenue produced by the established power stations for as long as they remain economically viable (that is can cover their direct operational costs) and so in the accounting profits and cash flows delivered by Eskom.

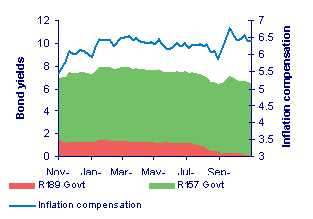

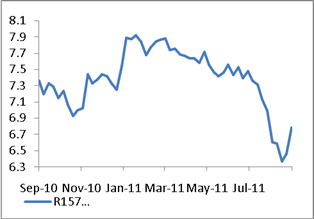

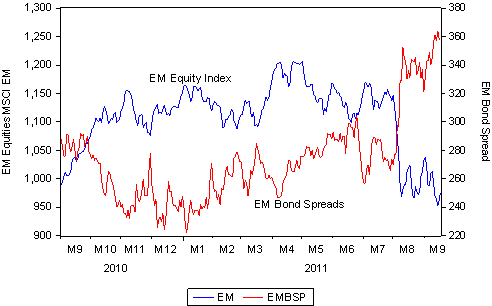

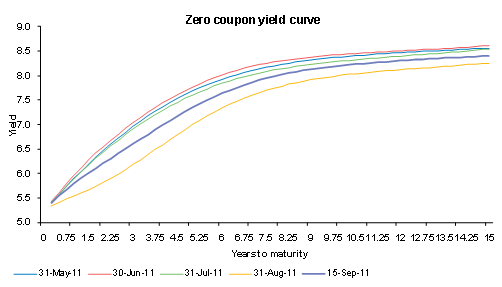

Power plants, once constructed, can be expected to have very long economic lives as Eskom’s history confirms. We have argued that the right price to charge current consumers for electricity today is the tariff that would provide the owners of Eskom (the RSA government) with an appropriate risk adjusted return on capital. We have judged this to be about 2% p.a. above the government’s own cost of raising long term capital, as represented by the yield on long term RSA bonds. That is to say, an extra return of about 2% pa over the cost of borrowing, given the low risk nature of an electric utility Eskom with monopoly powers, would seem the right price.

We also argued that the issue of the right tariff and the appropriateness of the real investment decisions to be made in additional electricity capacity should not be confused with how the additional capacity should best be funded (that is, with debt or equity capital). We argued that the SA government should either provide the capital in the form of an infusion of equity capital or by guaranteeing the debts of its wholly owned subsidiary – so reducing the funding costs to its potential minimum. We also indicated that a low risk business like an electricity utility could be expected to fund most of its expansion with debt rather than equity capital. We argued that it would be poor economics and unhelpful economic policy to overcharge, that is to tax current consumers for electricity, to finance the expansion of Eskom. Current and future consumers could be expected to pay the right price for electricity. That is, enough to provide an appropriate return on capital: no more or no less.

When we simulated the operational costs of a new power station of the scale planned by Eskom with a required return of 10% pa, we came up with a tariff to be charged today of the order of the 40c per Kilowatt Hour currently being charged. Our own sense is that inflation adjusting this tariff over the foreseeable future would be sufficient to the purpose of recovering the full cost of generating and distributing electricity in SA. We would be inclined to agree that a further 25% increase in the tariff would be a step too far. Economic growth would benefit greatly from competitively priced electricity in SA.

We would also recommend that Eskom maintains an appropriately high debt to equity ratio of the order of 90% debt and 10% equity. Further, to maintain this recommended debt to equity ratio, current tax payers could benefit from their profitable stake in Eskom through a substantial flow of dividends and tax payments. This year, despite its much improved finances, Eskom is not paying a dividend nor is it paying much by way of actual taxes. The income tax reported in its accounts is an impressive R3.3bn. The actual cash tax paid reported in its cash flow statement is a mere R151m and even less than the cash tax of R210m paid the year before.

To view the graphs and tables referred to in the article, see Daily Ideas in the Daily View: Daily View 30 June: Eskom: Surprise, Surprise – Eskom is awash with cash