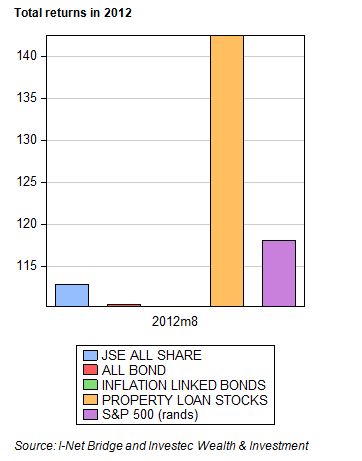

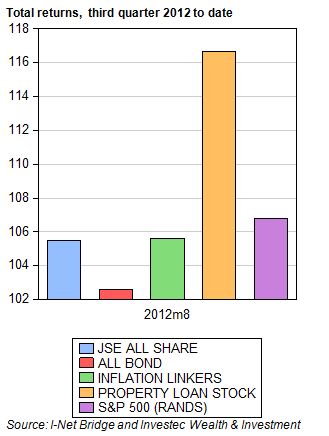

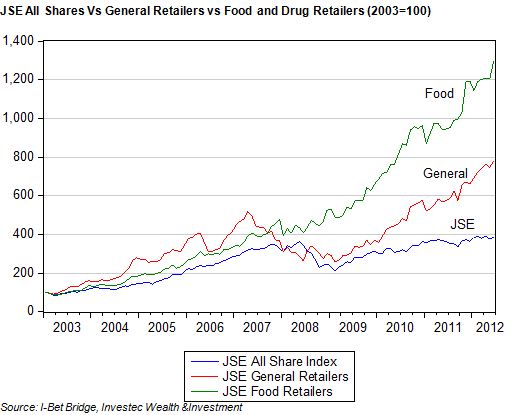

Investors on the JSE enjoyed outstandingly good returns in 2012 of about 26%, and have also done well over the past decade. We examine the factors behind this performance and what could wait in store in 2013.

Another outstanding year on the JSE

Investors on the JSE enjoyed outstandingly good returns in 2012 of about 26%. These returns concluded a decade of outstanding performance. Average returns on the JSE over the past 10 years have more than compensated for equity risks, as we show below. An extra four or five per cent a year from equities would have been good enough. The JSE provided much more than this.

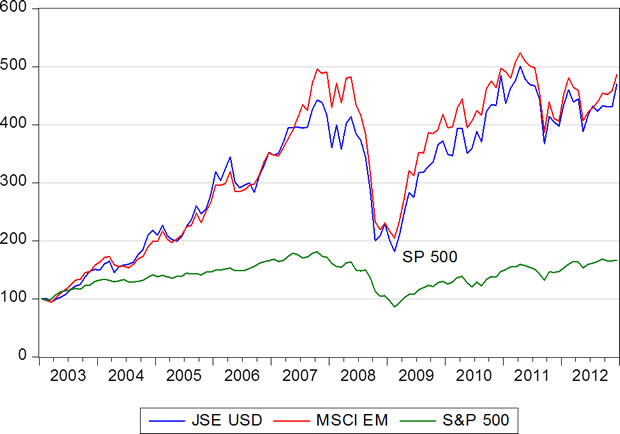

A wonderful decade for investors on the JSE and other emerging markets

Over the past 10 years (1 January 2003- 31 December 2012) annual returns on the JSE (calculated each month) averaged 18.4% p.a. The SA All Bond Index (ALBI) returned an average 9.2% p.a and the money market, represented by the three month interbank lending rate (JIBAR) returned an average 7.87% p. a. before any fees. Since inflation averaged 5.5% over the same period, real returns from all the asset classes were satisfactory but not nearly as good as those provided by the equity market.

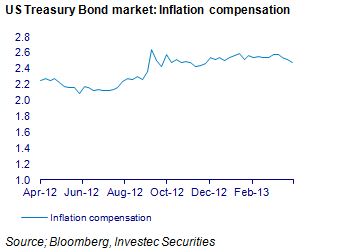

These returns were also excellent when translated into US dollars. In US dollar terms the JSE returned 16.4% p.a on average over the last 10 years, very much in line with the equally outstanding returns realised by the average emerging market – represented by the MSCI EM Index – that provided average returns in US dollars of 16.5% p.a. over the 10 year period. The S&P 500 Index realised only 5.8% p.a on average over the same period. It should be appreciated that the 10 years includes the very severe impact on share markets of the Global Financial Crisis of 2008- 09; when at its worst in February 2009, the JSE was 49% lower than a year before and 80% lower in US dollars. That same month the S&P 500 was 59% down on February 2008, while the EM Index was 87% lower.

Total returns: US$100 invested on 1 January 2003, with dividends reinvested (2003=2012)

Source: I-Net Bridge, Investec Wealth & Investment

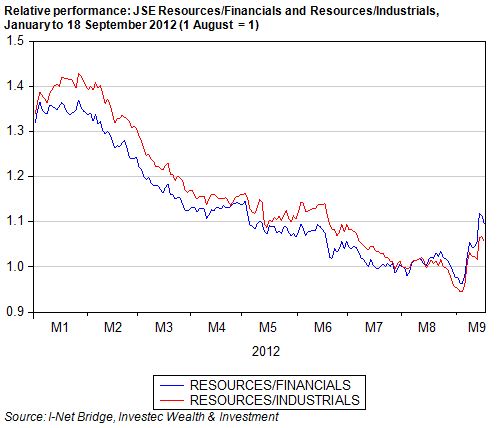

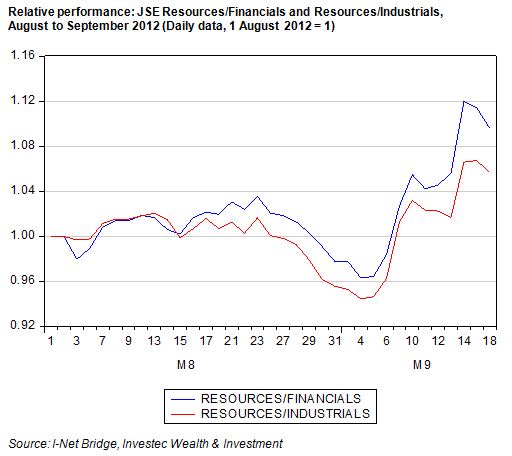

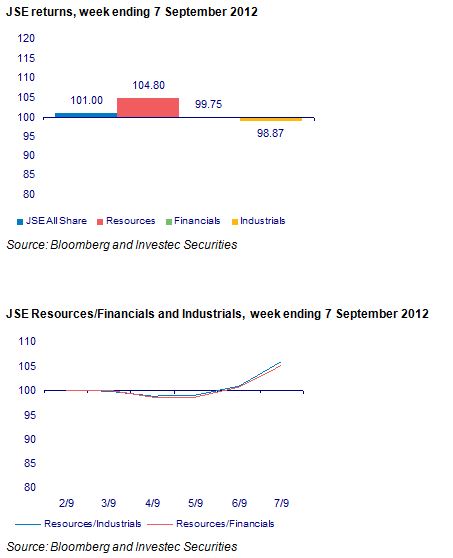

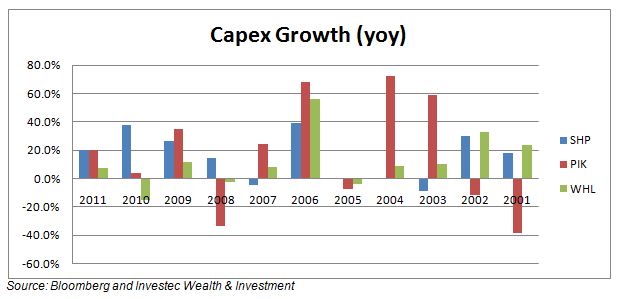

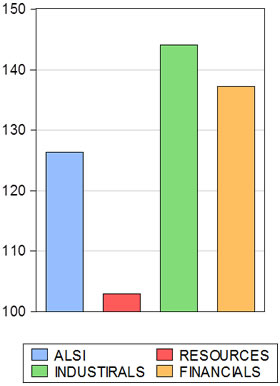

The winner was JSE Industrials, not Resources

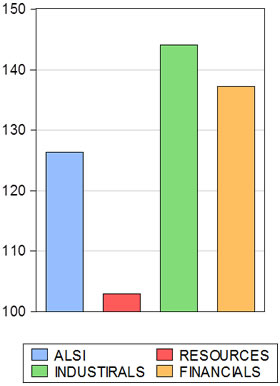

Investors on the JSE in 2012 would have done especially well had they concentrated their portfolios on Industrial rather than Resource companies. The JSE Industrial Index returned over 44% in 2012 while the Resource Index provided a total return of less than 3%. (See below)

JSE total returns in 2012

Source: I-Net Bridge, Investec Wealth & Investment

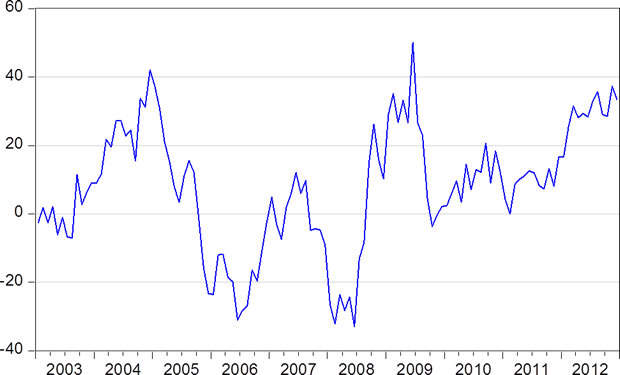

The game changer on the JSE: Industrials or Resources?

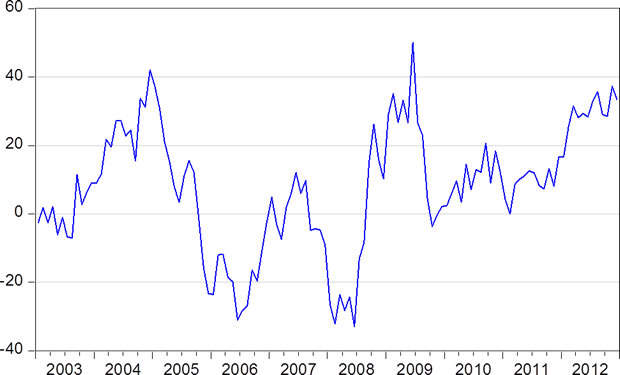

Such outperformance by JSE Industrials over Resources is by no means an unusual event. It should be clear that for active fund managers anticipating these differences in returns is the key to beating the market as a whole, so adding value for their clients after fees.

Difference in annual returns: JSE Industrials vs JSE Resources (2003- 2012)

Source: I-Net Bridge, Investec Wealth & Investment

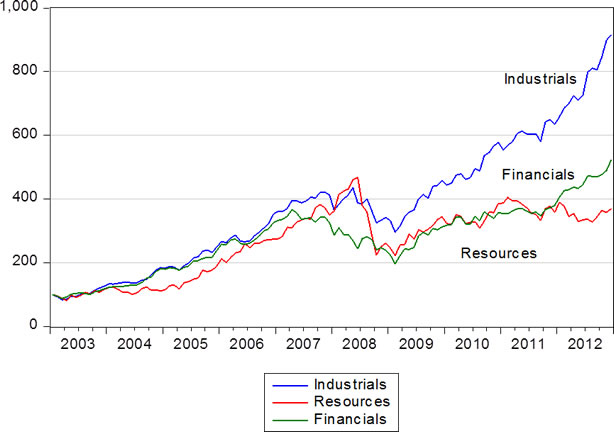

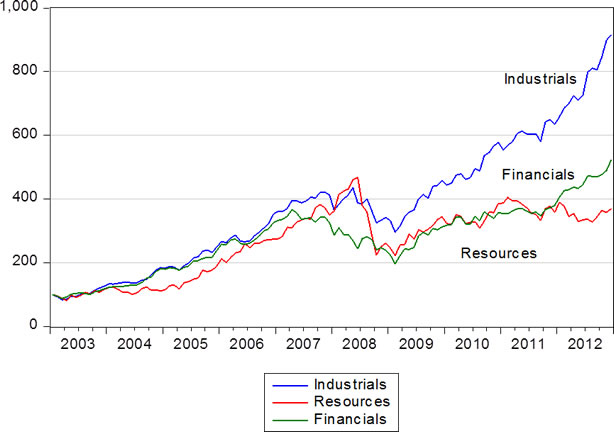

JSE Industrials have provided far superior returns than the average Resource company (for significantly less risk) over the past 10 years. As we show below, R100 invested in the Industrial Index on 1 January 2003, with dividends reinvested, would have accumulated an impressive value of over R900 by the end of 2012. The same R100 invested in the Resources Index would have yielded less than R400.

Cumulative returns on the JSE: Industrials vs Financials vs Resources. Value of R100 invested on 1 January 2003

Source: I-Net Bridge, Investec Wealth & Investment

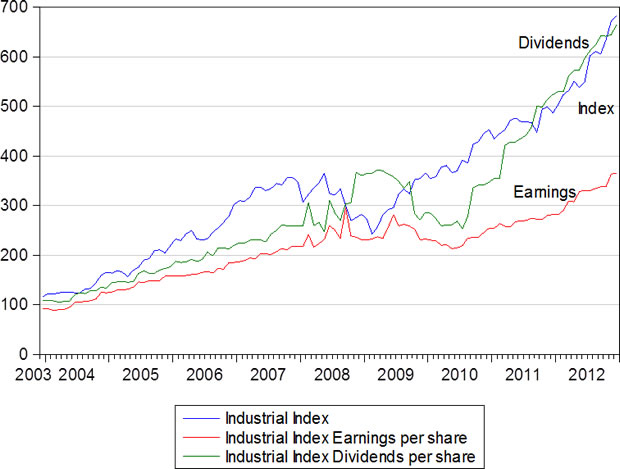

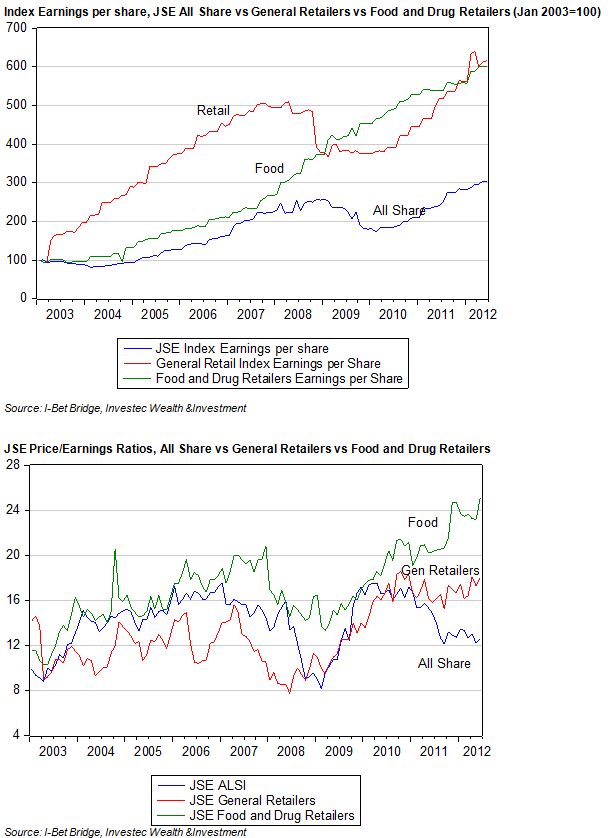

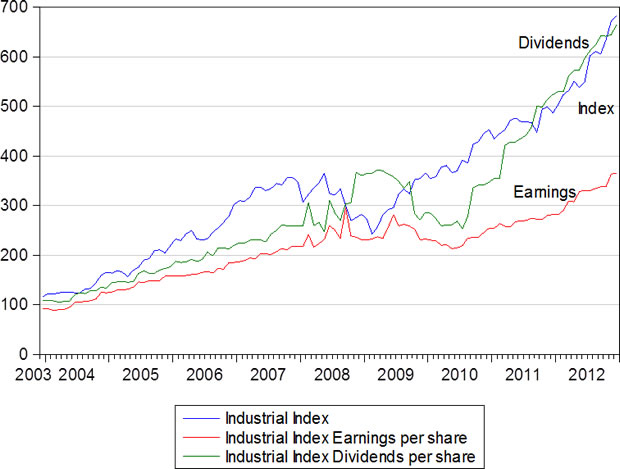

The outstanding performance of the JSE Industrial Index (a market capitalisation weighted index) is fully explained by the economic performance of the companies included in the index. Rising share values have been lifted by a rising tide of reported earnings and dividends. Both the value of the Industrial Index and the dividends distributed have increased by 7 times since 2003. The payout ratio of earnings to dividends has declined from 3.2 times dividends in 2003 to 2.1 times in December 2012.

If the past were to be the guide to future action it can be expected that the weight given to Resources in the representative SA portfolio will decline and that given to Industrials will increase. That Resources have a large weight on the JSE All Share Index does not justify anything like the same weight in SA portfolios on a risk adjusted basis. We should expect SA investors to reduce their exposure to resource companies to something like the international norm – which would be about a 10% weighting.

The JSE Industrial Index, dividends and earnings per share (January 2003=100)

Source: I-Net Bridge, Investec Wealth & Investment

Not all Industrial companies on the JSE are alike in their exposure to the SA and global economies

The Industrial Index of the JSE however combines companies with very different exposures to the SA and global economies. Dominating the Index by market value are companies that we describe as Industrial Hedges. These are companies that are heavily dependent for their sales, costs and profits on the global economy rather than the SA economy. Richemont (CFR) is a very good example. Its luxury goods are all produced outside SA and very few of them are sold in SA. SABMiller (SAB) is a global rather than a SA brewer. Aspen (APN) in pharmaceuticals, MTN in mobile networks and Naspers (NPN) in internet, have joined the ranks of the companies with much more at stake outside rather than inside the SA economy. British American Tobacco (BTI), now the largest company listed on the JSE, is another large Industrial Hedge, ie little affected by SA interest rates or the state of the SA economy. Their rand values furthermore will tend to go up and down in line with movements in the exchange value of the rand.

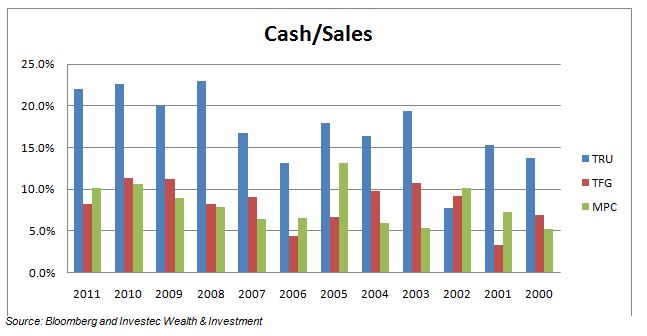

These Industrial Hedges are to be usefully contrasted with the SA economy plays – the retailers, banks, property and logistics companies listed on the JSE whose top and bottom lines react to the SA economy. Their share market performance is SA interest rate sensitive and a strong rand, low inflation and low interest rates are very helpful to their sales volumes and operating margins. A weak rand and the higher inflation and interest rates that may follow a weaker rand will damage their ability to earn profits and grow dividends.

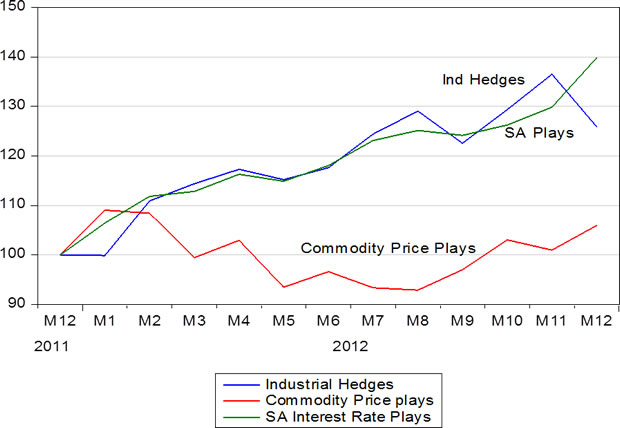

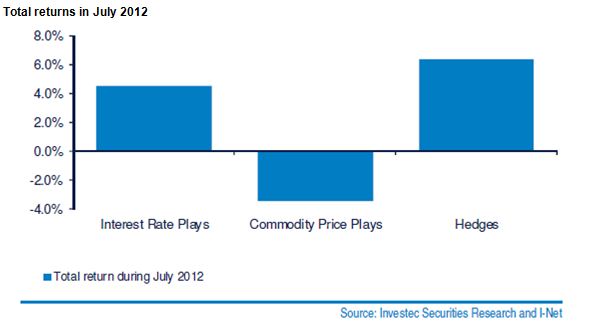

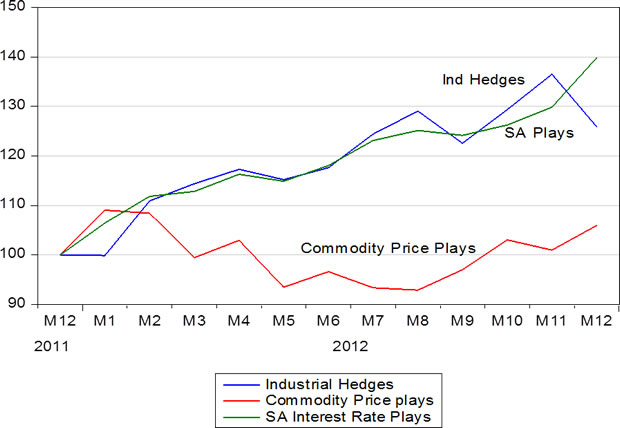

In 2012 these two categories of large industrial companies performed very similarly on both the earnings and valuation fronts as we demonstrate in the chart below. We have created Indexes for these different groups of JSE companies, have measured Index earnings per share and have compared them to each other and to the Resource Companies (excluding the gold mining stocks), which we call commodity price plays. As may be seen the Industrials gained ground on the commodity price plays in 2012 on the basis of much stronger and more consistent growth in earnings and (not shown here) in dividends.

Industrial Hedges vs SA Plays vs Commodity Price Plays; total returns (1 January 2012 – 31 December 2012)

Source: I-Net Bridge, Investec Securities, Investec Wealth & Investment

Index earnings per share: Industrial hedges vs SA Plays vs Commodity Price Plays (1 January 2012=100)

Source: I-Net Bridge, Investec Securities, Investec Wealth & Investment

The surprisingly good performance of the SA plays in 2012

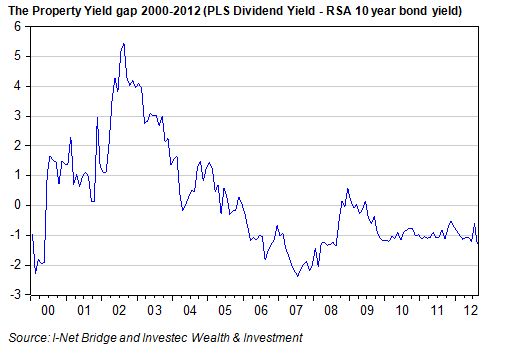

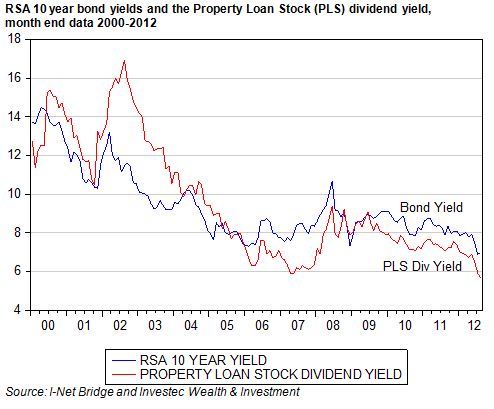

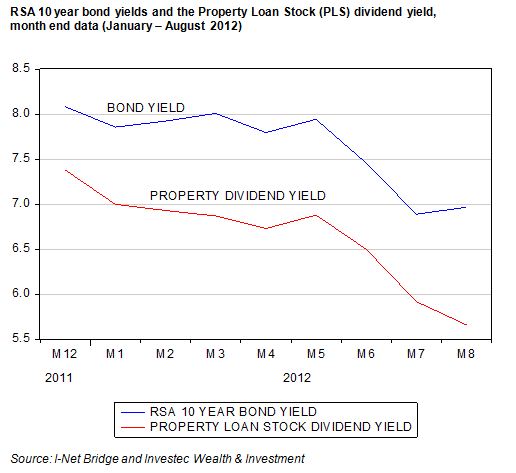

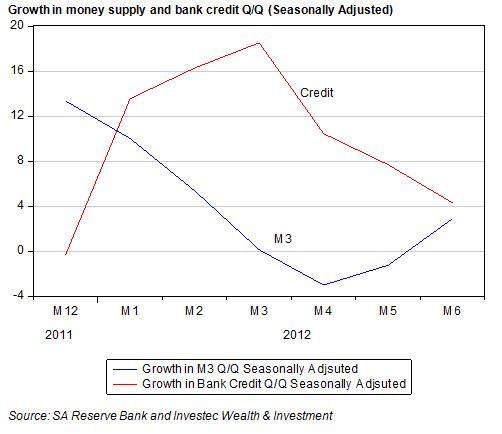

The surprising feature of 2012 is that while the Resources companies felt the cold draft of a weaker global economy and lower commodity prices, the Industrials continued to grow their earnings despite slow growth. Furthermore the economic performance of the SA economy plays was compromised by the weaker rand that put pressure on imported input costs and pricing power. Yet the SA plays were greatly assisted by low and stable interest rates. The weaker rand and the higher rate of inflation did not lead to higher interest rates, as might have been expected. The SA Reserve Bank in its interest rate settings and commentary helpfully (and correctly in our view) adopted a dual mandate – a concern for growth as well as inflation. It can be expected to continue to influence the economy in this way.

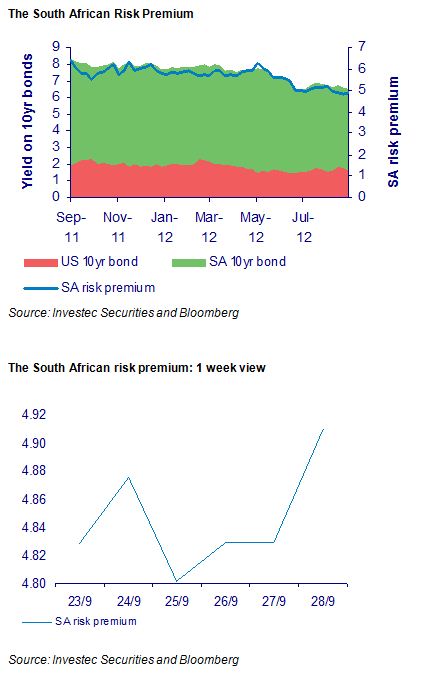

There was no demand side pressure on prices, as the Bank pointed out, and given the weak global economy and the impact this was having on export prices and volumes – harmed additionally by strike action in SA – domestic demand needed encouragement in the form of lower interest rates (and received it). Longer term interest rates also moved lower –despite more inflation – helped by a global search for yield that was found in the SA bond market.

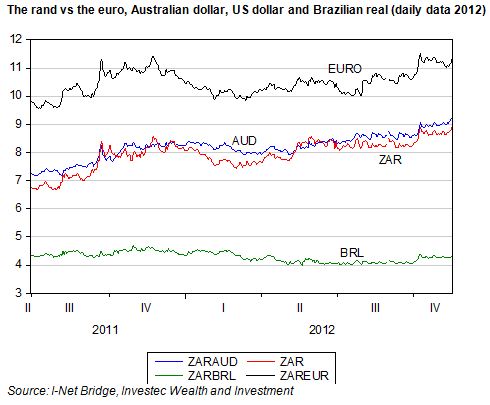

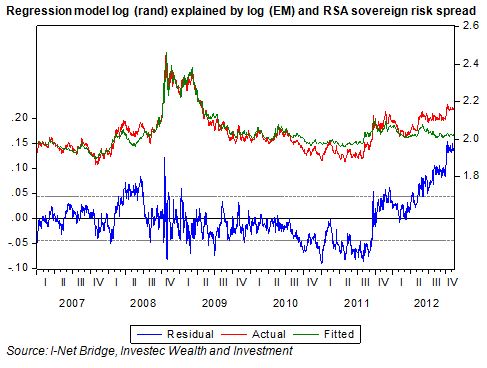

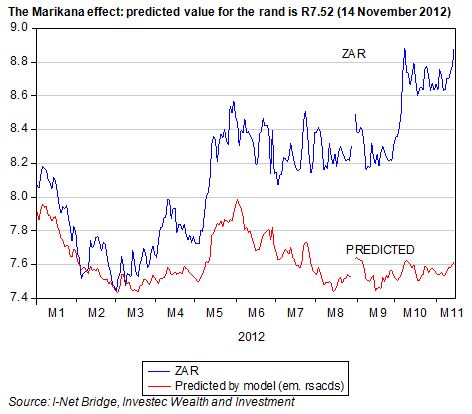

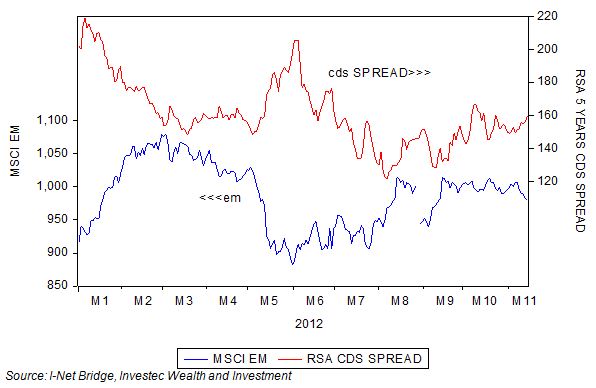

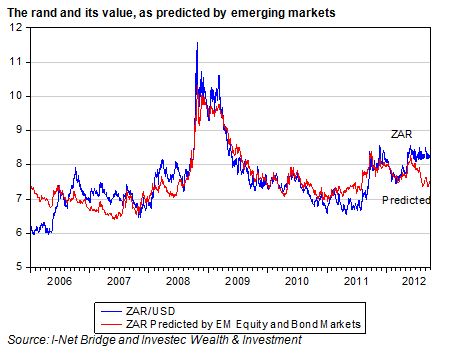

Explaining the performance of the rand in 2012 and beyond

The weaker rand since year end will have been helpful to the value of the Industrial Hedges and perhaps more helpful to the commodity price plays – provided they can maintain or increase output in the face of Industrial action. A weaker rand is not helpful to the SA economy plays. Yet the danger posed to these companies and the service sector of the SA economy in the form of higher interest rates still seems highly remote.

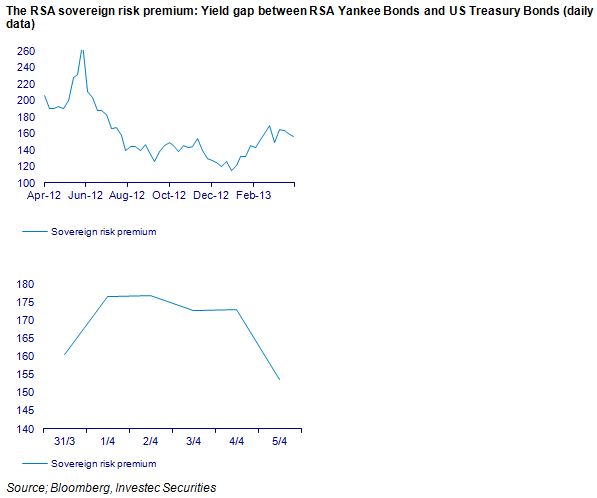

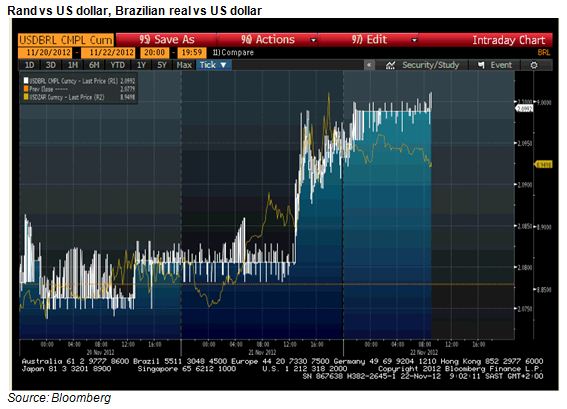

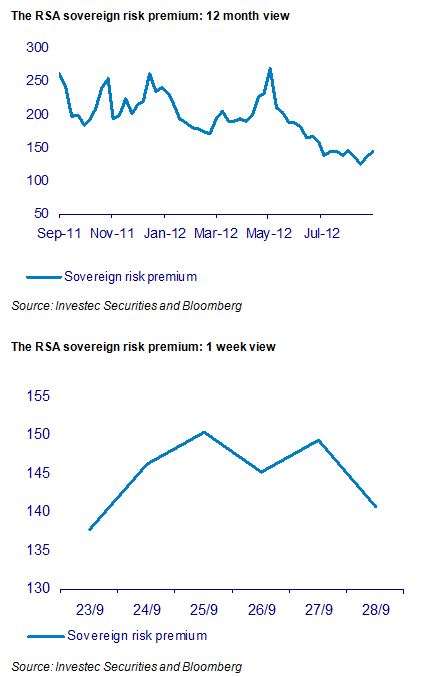

The rand has demonstrated much SA specific weakness linked to the Industrial action and the threat poor labour relations poses to the SA economy and its growth prospects. The rand is about 15% weaker than it would have been if, as before, emerging market risks and market developments had continued to dominate its exchange value. Such forces, including the appetite for emerging market equities and bonds, will continue to influence the rand from day to day and month to month. But strength in the rand will depend also on perceptions of SA economic policy strengths and weaknesses. Any sense that the SA government is making progress on the labour relations front (not an entirely unrealistic proposition) will be helpful to the rand at its current much weaker levels.

Rotation by SA Fund Managers between Industrials and Resources will not matter very much to the outcomes on the JSE

It should be appreciated however that these outcomes, in the form of relative performance by the different sectors of the JSE will not be decided by SA fund managers “rotating” the weight of their portfolios between Industrials and Resources. All the major companies listed on the JSE, be they Industrial or even more obviously Resource companies have one important thing very much in common. They are all well in the sights of global investors who can hold large proportions of the shares issued by JSE listed companies.

These decisive offshore investors do not compare the relative merits of JSE listed Industrials or Resource companies. They compare JSE listed companies – companies often also listed on other stock markets – with their peers be they retailers or banks or iron ore or gold producers. The JSE listed companies have proved very competitive over the past 10 years in the flow of earnings and dividends they have delivered and are expected to deliver. Hence the fact that the JSE Indexes in US dollar compare very favourably with other emerging markets. Fair rather than foul winds blowing across the global as well as the SA economy would make it easier for the JSE listed cohort to compete for the attention of global investors.

Drawing the conclusions for asset allocations in 2013

There is good reason for us to believe that global equities will continue to offer good value despite their strength in 2012 and despite further strong advances made in early 2013. However, a repeat of the excellent JSE returns realised in 2012 must be regarded as unlikely.

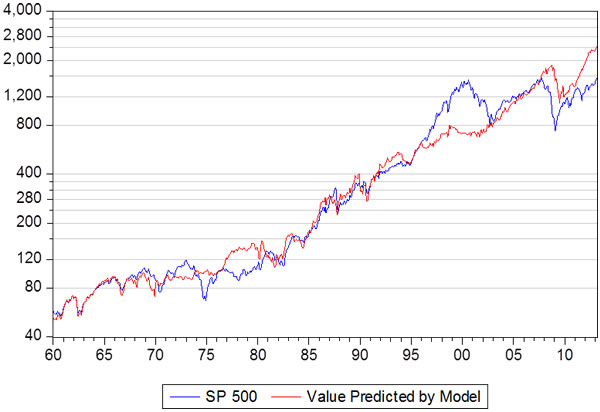

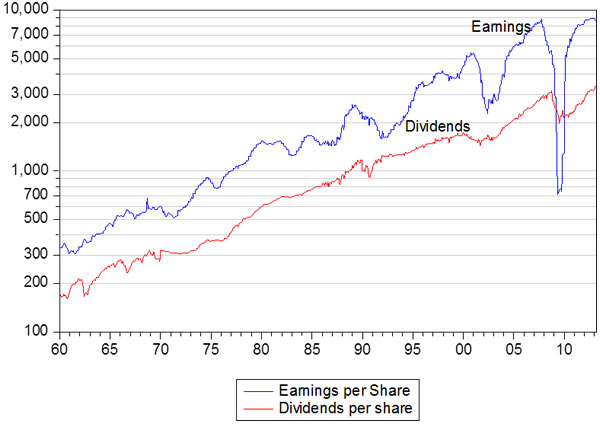

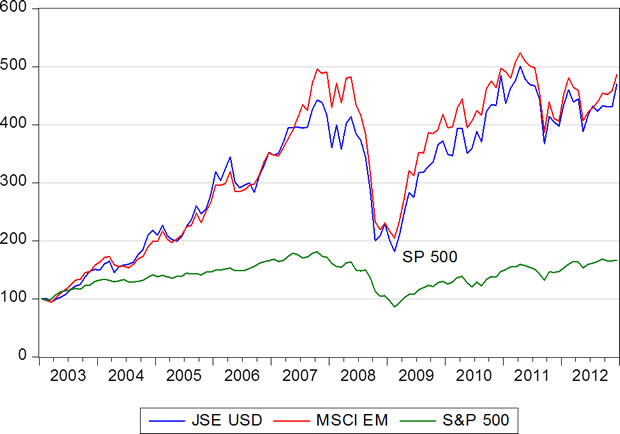

The more conspicuous equity value opportunity appears in the developed equity markets that have lagged behind the emerging markets over the past 10 years as investors moved large flows of cash out of equities into bonds and cash. When trailing dividends or earnings on the S&P 500, at record levels, are discounted by very low long dated US Treasury yields, the S&P 500 appears to be deeply undervalued. Should the S&P 500 move strongly ahead this would provide strong support for other equity markets. Clearly these S&P valuations would be threatened by any sharp reduction in earnings or an increase in 10 year Treasury Bond yields to something like normal levels of around 4% p.a. from their current less than 2% p.a.

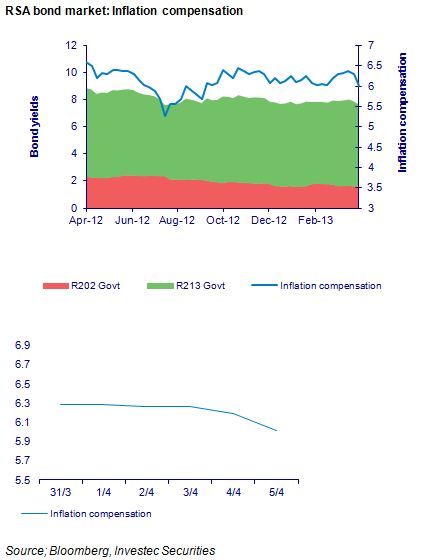

It would however take a strong recovery in the US economy to lift interest rates. And such a recovery would mean further growth in earnings and dividends. The asset class most vulnerable to any strong recovery in the global economy is developed economy bonds. A mixture of faster growth and higher inflation that would raise bond yields would do great damage to the market value of long dated government bonds that are now priced at such elevated levels. The holders of developed economy government bonds, Treasury bonds, bunds, gilts or Japanese bonds could best hope for a further extended period of global economic weakness. Even then long term interest rates would be unlikely to decline further and as in 2012 the appeal of dividend yields above short and long term interest rates would help support equity markets.

Given the danger to holders of government bonds of rising long term interest rates and the opportunity in what we regard as very conservatively valued equities, which provide protection against inflation. Equities become especially attractive when inflation comes with faster growth (as it may well do next time round). We accordingly continue to recommend equities in general over long dated fixed interest.

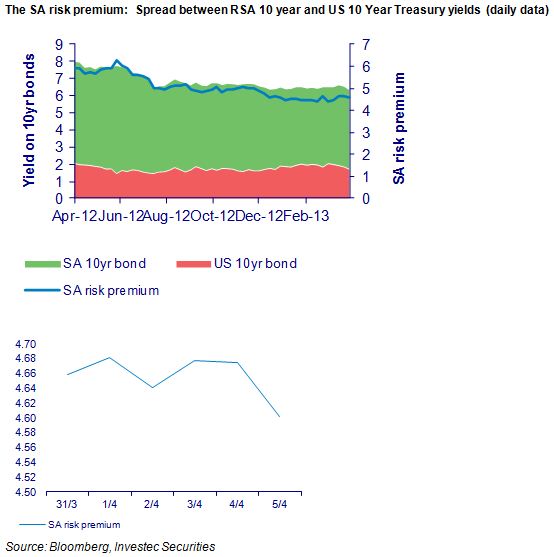

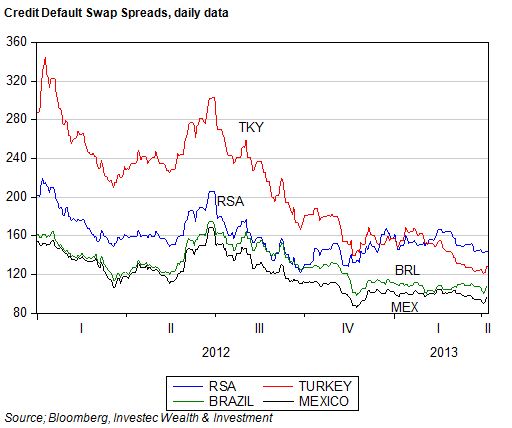

When it comes to fixed income we would prefer the protection of higher yields offered by high yield corporate credit or emerging market government debt. A narrowing of risk spreads, given any sustained economic recovery, could compensate in part for higher benchmark bond yields. But if safety is to be sought, then we would prefer short dated debt – even cash to long dated fixed interest ordinarily defined as safe havens.

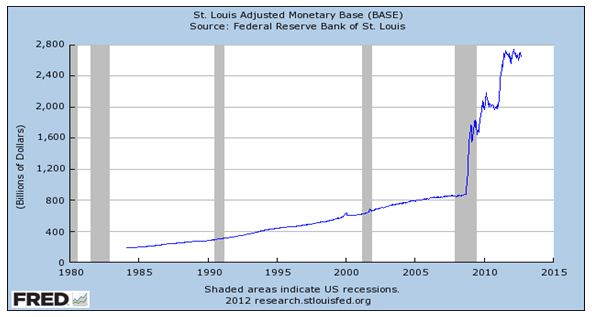

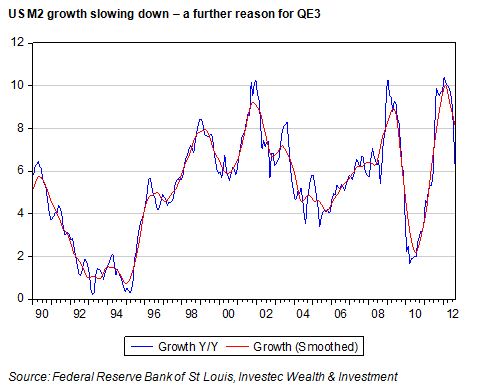

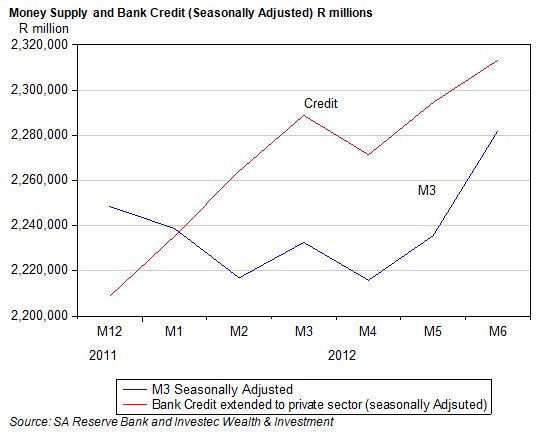

These are anything but ordinary times in financial markets that have been made flush with cash issued by central banks in order to save their banking systems. When the banks prefer to lend some of their excess cash reserves, as they appear to be doing in the US – where bank lending and balance sheets are now growing at about a healthy 10% p. a rate – economic growth and more inflation is likely to follow.

The case for global equities seems to us to be improving. When the choice turns to South African equities the Industrial Hedges, exposed as they are to the global economy and protected against rand weakness, offer the prospect of decent returns with less risk than either the commodity plays or the SA plays. The case for the SA plays over the Industrial Hedges depends on a recovery in the rand from its current depressed levels.

The benefits the commodity plays will gain from a global recovery and higher commodity prices could be augmented by any rand weakness associated with SA specific risks. When revenues are priced in US dollars and costs are incurred in rands, operating margins for SA mining operations can widen to their advantage. However any SA specific risks are likely to be linked to labour troubles on the mines, which would be expected to disrupt operations. These expectations would reduce the appeal of the Resources companies with significant operations in South Africa ,even if the rand weakens. Best for SA mines would be a degree of rand strength, associated with less global risk aversion and higher commodity prices as well as progress in labour relations on the mines.

The performance of the rand will be particularly important in 2013 for relative performance on the JSE. For rand strength we would prefer the SA plays and for rand weakness the Industrial Hedges. The commodity price plays, while undoubtedly offering value, given a cyclical recovery in their earnings, will need a degree of rand strength for SA as well as global reasons to make a strong case for investors. And so – if there is a recovery in the rand – the SA plays might again offer superior returns over Resources in 2013.

Rand weakness for both global and SA reasons would clearly favour the Industrial Hedges over both the SA Plays and the commodity price plays. Our own inclination is to favour a modest degree of rand strength coupled with a sense that the global economy will remain on the recovery path. Given such circumstances it is difficult to strongly favour any one class of equities over the other. A generally favourable global environment for equities in 2013 will reward good stock picking. The search for companies and their management with excellent long term prospects may prove especially rewarding.