Understanding investment trusts and how they can add value for shareholders regardless of any apparent discount to NAV.

Remgro, through its various iterations, has proved to be one of the JSE’s great success stories. It has consistently provided its shareholders with market beating returns. Still family controlled, it has evolved from a tobacco company into a diversified conglomerate, an investment trust, controlling subsidiary companies in finance, industry and at times mining, some stock exchange listed, others unlisted. Restructuring and unbundling, including that of its interests in Richemont, have accompanied this path of impressive value creation for patient shareholders.

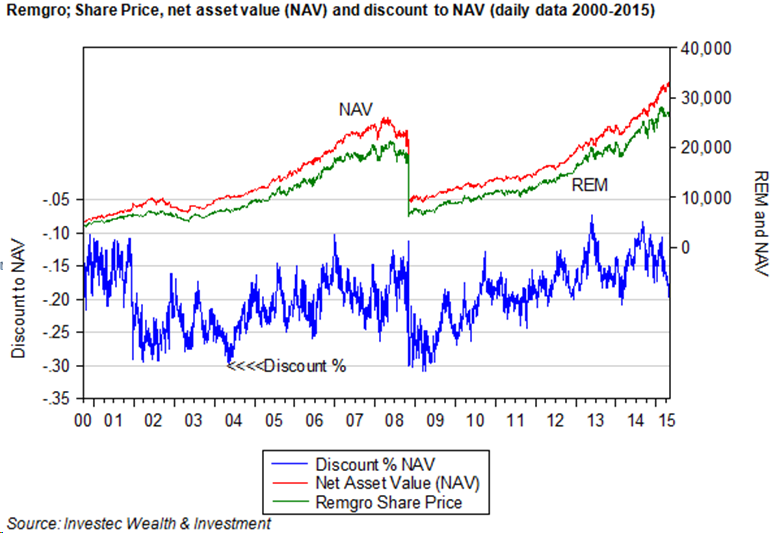

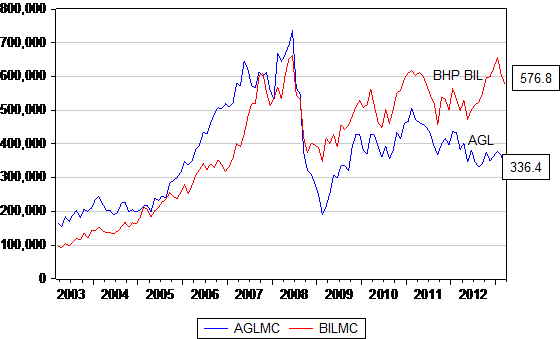

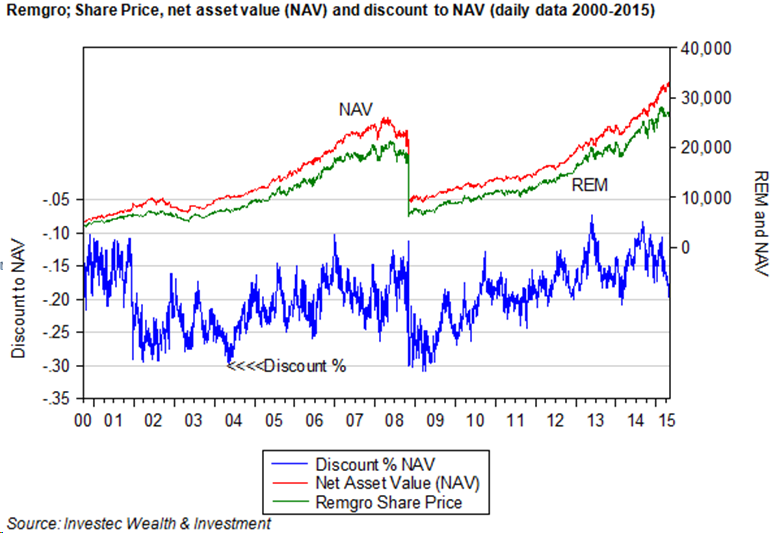

The most important recent unbundling exercise undertaken by Remgro was in 2008 when its shares in British American Tobacco (BTI), acquired earlier in exchange for its SA tobacco operations, were partly unbundled to its shareholders, accompanied by a secondary listing for BTI on the JSE. A further part of the Remgro shareholding in BTI was exchanged for shares in another JSE-listed counter and investment trust, Reinet, also under the same family control, with the intention to utilise its holding of BTI shares as currency for another diversified portfolio, with a focus on offshore opportunities. Since the BTI unbundling of 2008, Remgro has provided its shareholders with an average annual return (dividends plus capital appreciation, calculated each month) of 23%. This is well ahead of the returns provided by the JSE All Share Index, which averaged 17% p.a over the same period. Yet all the while these excellent and market beating returns were being generated, the Remgro shares are calculated to have traded at less than the value of its sum of parts, that is to say, it consistently traded at a discount to its net asset value (NAV).

The implication of this discount to NAV is that at any point in time the Remgro management could have added immediate value for its shareholders by realising its higher NAV through disposal or unbundling of its holdings. In other words, the company at any point in time would have been worth more to its shareholders broken up than maintained as a continuing operation.

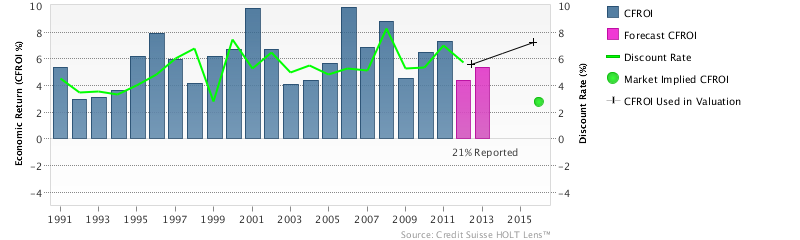

How then is it possible to reconcile the fact that a share that consistently outperforms the market should be so consistently undervalued by the market? It should be appreciated that any business, including a listed holding company such as Remgro, is much more than the estimated value of its parts at any moment in time. That is to say a company is more than the value of what may be called its existing business, unless it is in the process of being unwound or liquidated. It is an ongoing enterprise with a presumably long life to come. Future business activity and decisions taken will be expected to add to the value of its current activities. For a business that invests in other businesses, value can be expected to be added or lost by decisions to invest more or less in other businesses, as well as more or less in the subsidiary companies in which the trust has an established controlling interest. The more value added to be expected from upcoming investment decisions, the higher will be the value of the holding company for any given base of listed and unlisted assets (marked to market) and the net debt that make up the calculated NAV.

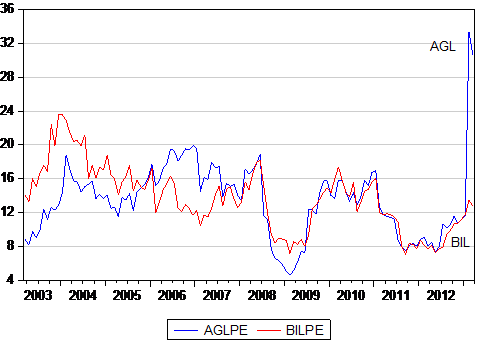

Supporting this assertion is the observation that not all investment trusts sell at a discount to NAV. Some, for example the shares in Berkshire Hathaway run by the famed Warren Buffet, consistently trade at a value that exceeds its sum of parts. Brait and Rockcastle, listed on the JSE, which invest in other listed and unlisted businesses, are currently valued at a significant premium to their sum of parts. Brait currently is worth at least 45% more than its own estimate of NAV while Rockcastle, a property owning holding company offers a premium over NAV of about 70%. PSG, another investment holding company, has mostly traded at a consistently small discount to NAV but is now valued almost exactly in line with its estimated NAV.

It would appear that the market expects relatively more value add to come from the investment decisions to be made by a Brait or Rockcastle or PSG, than it does from Remgro. The current value of the shares of these holding companies has risen absolutely and relatively to NAV to reflect the market’s expectation of the high internal rate of returns expected to be realised in the future as their investment programmes are unveiled. Higher (lower) expected internal rates of return are converted through share price moves into normal risk adjusted returns. The expected outperforming businesses become relatively more expensive in the share market – perhaps thereby commanding a premium over NAV – while the expected underperformers trade at a lower share price to provide the expected normal returns, so revealing a discount to NAV.

The NAV of a holding company however is merely an estimate, subject perhaps to significant measurement errors, especially when a significant proportion of the NAV is made up of unlisted assets. Any persistent discount to NAV of the Remgro kind may reflect in part an overestimate of the value of its unlisted subsidiaries included in NAV. The NAV of a holding company is defined as the sum of the market value of its listed assets, which are known with certainty, plus the estimated market value of its unlisted assets, the values of which can only be inferred with much less certainty. The more unlisted relative to listed assets held by the holding company, the less confidence can be attached to any estimates of NAV.

The share market value of the holding company will surely be influenced by the same variables, the market value of listed assets and the estimates of the value of unlisted assets minus net debt. But there will be other additional forces influencing the market value of the holding company that will not typically be included in the calculation of NAV. As mentioned, the highly uncertain value of its future business activities will influence its current share price. These growth plans may well involve raising additional debt or equity, so adding to or reducing the value of the holding company shares, both absolutely and relative to the current explicit NAV that includes only current net debt. Other forces that could add to or reduce the value of the holding company and so influence the discount or premium, not included in NAV, are any fees paid by subsidiary companies to the head office, in excess of the costs of delivering such services to them. They would detract from the value of the holding company when the subsidiary companies are being subsidised by head office. When fees are paid by the holding company to an independent and controlling management company, this would detract from its value from shareholders, as would any guarantees provided by the holding company to the creditors of a subsidiary company. The market value of the subsidiaries would rise, given such arrangements and that of the holding company fall, so adding to any revealed discount to NAV.

It should be appreciated that in the calculation of NAV, the value of the listed assets will move continuously with their market values, as will the share price of the holding company likely to rise or fall in the same direction as that of the listed subsidiaries when they count for a large share of all assets. But not all the components of NAV will vary continuously. The net debt will be fixed for a period of time, as might the directors’ valuations of the unlisted subsidiaries. Thus the calculated NAV will tend to lag behind the market as it moves generally higher or lower and the discount or premium to NAV will then decline or fall automatically in line with market related moves that have little to do with company specifics or the actions of management. In other words, the market moves and the discount or premium automatically follows.

If this updated discount or premium can be shown to revert over time to some predictable average (which may not be the case) then it may be useful to time entry into or out of the shares of the holding company. But the direction of causation is surely from the value attached to the holding company to the discount or premium – rather than the other way round. The task for management is to influence the value of the holding company not the discount or premium.

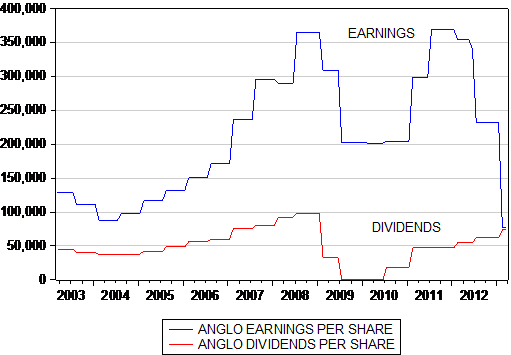

Yet any improved prospect of a partial liquidation of holding company assets, say through an unbundling, will add to the market value of the holding company and reduce the discount. After an unbundling the market value of the holding company will decline simultaneously and then, depending on the future prospects and expectations of holding company actions, including future unbundling decisions, a discount or premium to NAV may emerge. The performance of Remgro prior to and after the BTI unbundling conformed very well to this pattern. An improvement in the value of the holding company shares and a reduction in the discount to NAV on announcement of an unbundling – a sharp reduction in the value of the holding company after the unbundling and the resumption of a large discount when the reduced Remgro emerged. See figure 1 above.

The purpose of any closed end investment trust should be the same as that of any business and that is to add value for its shareholders by generating returns in excess of its risk adjusted cost of capital. That is to say, by providing returns that exceed required returns, for similarly risky assets. Risks are reduced for shareholders through diversification as the investment trust may do. But shareholders can hold a well diversified portfolio of listed assets without assistance from the managers of an investment trust. The special benefits an investment trust can therefore hope to offer its shareholders is through identifying and nurturing smaller companies, listed and unlisted, that through the involvement of the holding company become much more valuable companies. When the nurturing process is judged to be over and the listed subsidiary is fully capable of standing on its own feet, a revealed willingness to unbundle or dispose of such interest would add value to any successful holding company.

This means the holding company or trust will actively manage a somewhat concentrated portfolio, much more concentrated than that of the average unit trust. Such opportunities to concentrate the portfolio and stay active and involved with the management of subsidiary companies may only become available with the permanent capital provided to a closed end investment trust. The successful holding company may best be regarded and behave as a listed private equity fund. True value adding active investment programmes require patience and the ability to stay invested in and involved in a subsidiary company for the long run. Unit trusts or exchange traded funds do not lend themselves to active investment or a long run buy and hold and actively managed strategy of the kind recommended by Warren Buffett. A focus on discounts to estimates of NAV, to make the case for the liquidation of the company for a short term gain, rather than a focus on the hopefully rising value of the shares in the holding company over the long term, may well confuse the investment and business case for the holding company, as it would for any private equity fund. The success of Remgro over the long run helps make the case for investment trusts as an investment vehicle. So too for Brait and PSG, which are perhaps best understood as listed private equity and highly suited to be part of a portfolio for the long run.

Appendix

A little light algebra and calculus can help clarify the issues and identify the forces driving a discount or premium to NAV

Let us therefore define the discount as follows, treating the discount as a positive number and percentage. Any premium should MV>NAV would show up as a negative number.

Disc % = (NAV-MV)/NAV ……………………………………….. 1

Where NAV is Net Asset Value (sum of parts), MV is market value of listed holding company

NAV = ML+MU-NDt ……………………………………………. (2)

Where NAV is defined as the sum of the maket value of the listed assets held by the holding company. MU is the assumed market value of the unlisted assets(shares in subsidiary companies) held by the holding company and NDt is the net debt held on the books of the holding company – that is debt less cash.

Note to valuation of unlisted subsidiaries MU;

MU may be based on an estimate of the directors or as inferred by an analyst using some valuation method- perhaps by multiplying forecast earnings by a multiple taken from some like listed company with a similar risk profile to the unlisted subsidiary. Clearly this estimate is subject to much more uncertainty than the ML that will be known with complete certainty at any point in time. Thus the greater the proportion of MU on the balance sheet the less confidence can be placed on any estimate of NAV.

The market value of the holding company may be regarded as

MV=ML+MU-NDt+HO+NPV………………………………………………..(3)

That is to say all the forces acting on NAV, plus the assumed value of head office fees and subsidies (HO)activity and of likely much greater importance the assessment markets of the net present value of additional investment and capital raising activity NPV. NPV or HO may be adding to or subtracting from the market value of the holding company MV.

A further force influencing the market value of the holding company would be any liability for capital gains taxes on any realisation of assets. Unbundling would no presumably attract any capital gains for the holding company. These tax considerations are not taken up here

IF we substitute equations 2 and 3 into equation one the forces common to 2 and 3 ML,MU,NDt cancel out and we can conveniently write the Discount as the ratio

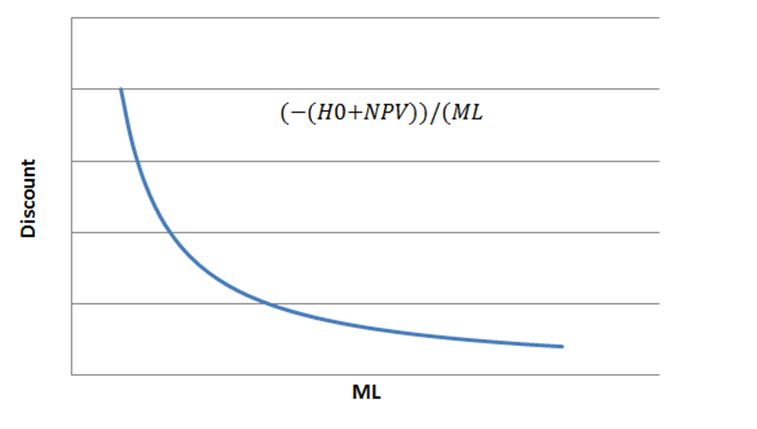

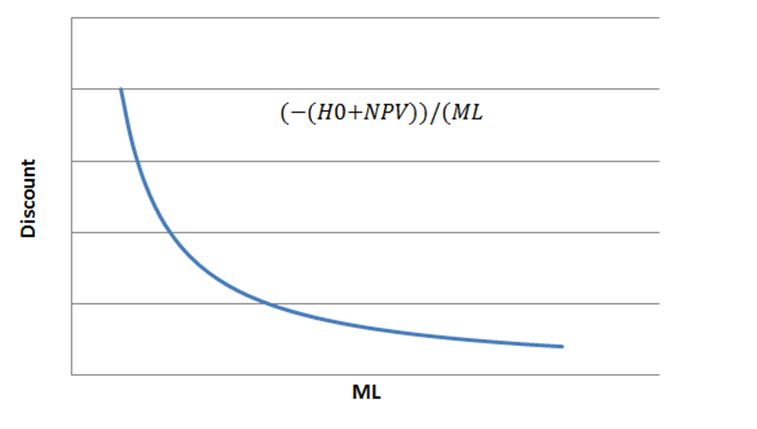

Disc= – (H0+NPV)/(ML+MU-NDt ) ………………………………………..(4)

Clearly any change that reduces the numerator (top line) or increases the denominator (bottom line) of this ratio will reduce the discount. Thus an increase in the value attached to the Head Office or the value of future business will reduce the discount. ( These forces are preceded by a negative sign in the ratio) A large increase in the value attached to investment activity will also reduce the discount and might even turn the ratio into a negative value, that is a premium. Clearly should the market value of listed or unlisted assets rise or Net Debt decline (become less negative) the denominator would attain a larger absolute number, so reducing the discount. The implication of this ratio seems very obvious. If the management of a holding company wishes to add value for shareholders in ways that will reduce any discount to NAV or realise a premium then they would need to convince the market of their ability to find and execute more value adding positive NPV projects. Turning unlisted assets into more valuable listed assets would clearly serve this purpose

Some calculus might also help to illuminate the forces at work. Differentiating the expression would indicate clearly that the discount declines for increases in H0 or NPV

That is dDisc/dNPV or dDisc/dHO= -1/(ML+MU-NDt)

This result indicates that the larger the absolute size of the holding company the more difficult it will become to move the discount through changes in the business model

Differentiating for small changes in the variables in the denominator is a more complicated procedure but would yield the following result for dML or dMU or dDNt

For example dDisc/DML= -(H0+NPV)/(ML+MU-NDt)^2

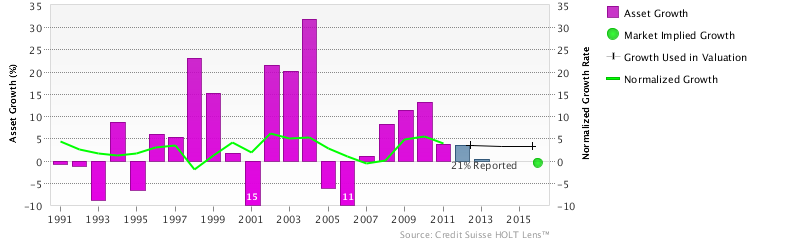

Again it may be shown that the impact of any change in ML,MU or NDt will be influenced by the existing scale of the listed assets held ML. The larger the absolute size of ML the less sensitive the discount will be to any increase in ML. The same sensitivities would apply to changes in MU or NDT. This reaction function is illustrated below