The SA chances of an interest rate cut have improved markedly. Insuring against the risks of more inflation has also become more expensive. What does this mean for equities?

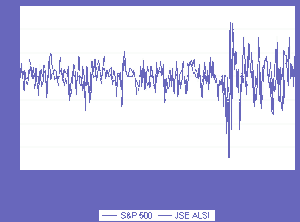

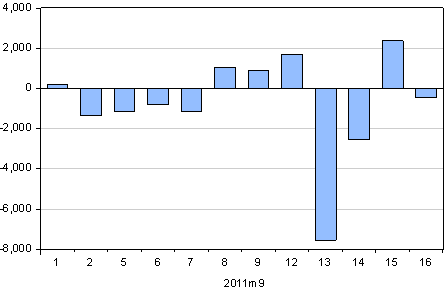

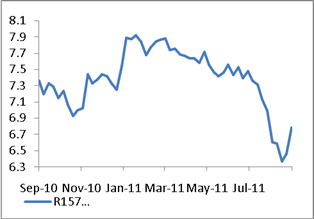

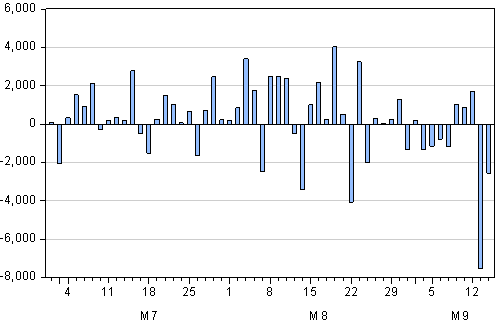

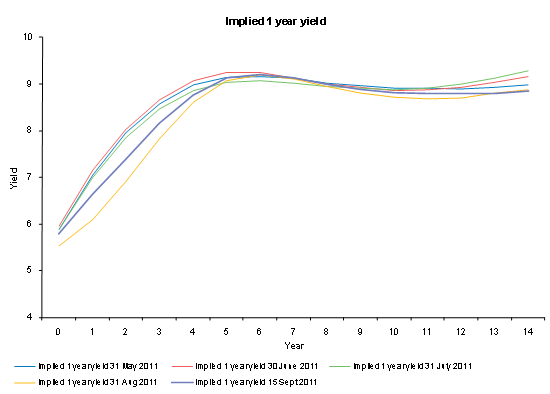

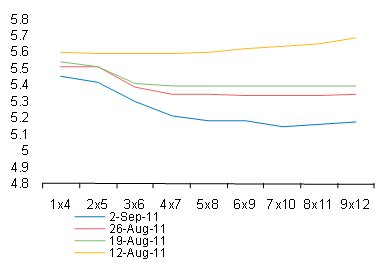

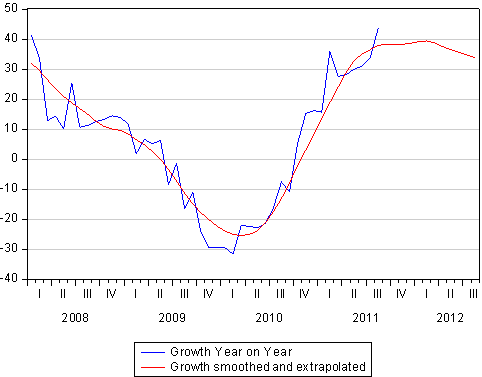

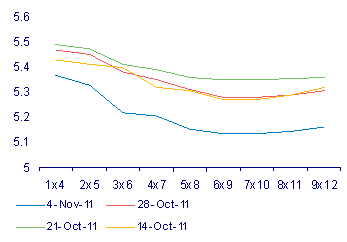

This week the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) of the Reserve Bank will meet to set the Bank’s repurchase (repo) rate. Their deliberations were preceded last week by a very sharp downward shift in the Forward Rate Agreements (FRAs) set by the commercial banks. These rates, at which the banks are willing to lend for three months in three months’ time and beyond, indicate the direction of the repo rate to be set by the MPC.

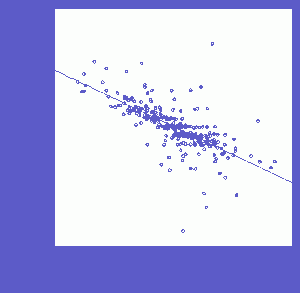

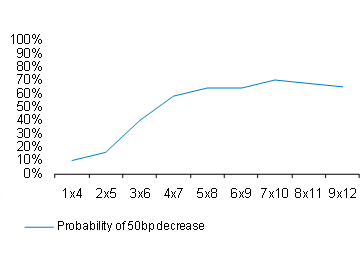

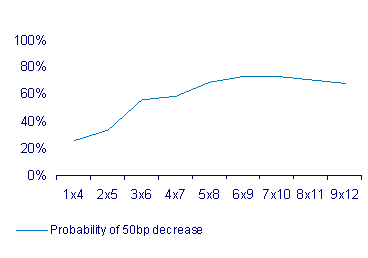

With the bodily shift of the FRA curve lower and the negative tilt of the FRAs, the SA banks have significantly raised the prospect of a cut in short term interest rates in the near future. This probability can be inferred from the level and direction of the forward rates. As we show below the probability of a 50bps reduction in short term interest rates is about 20% this week, rising to over a 70% chance of a cut within six months.

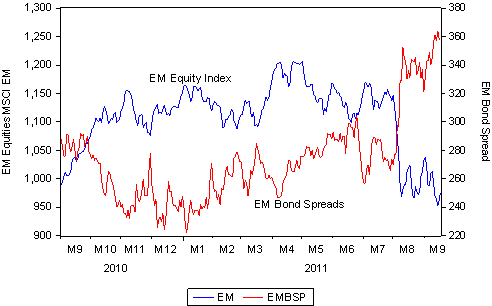

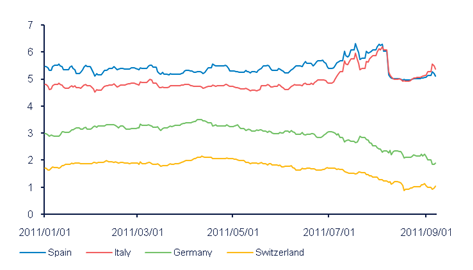

We had judged that the MPC had come very close to cutting rates at its last meeting, having every good reason to do so, given that the economy had been operating well below its potential. But the MPC then blinked and passed on the opportunity. Since then the MPC would have noticed how the Australians and the Europeans have cut rates with a deteriorating global and European growth outlook.

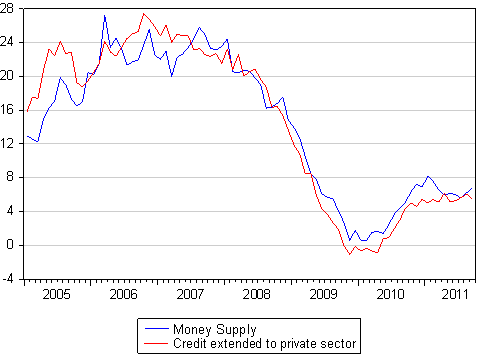

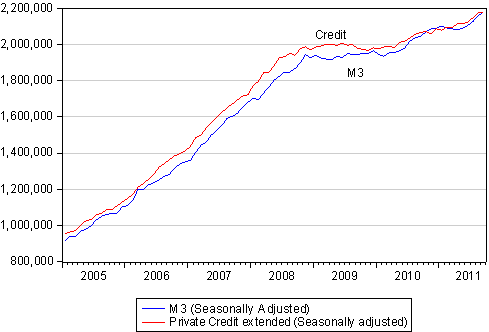

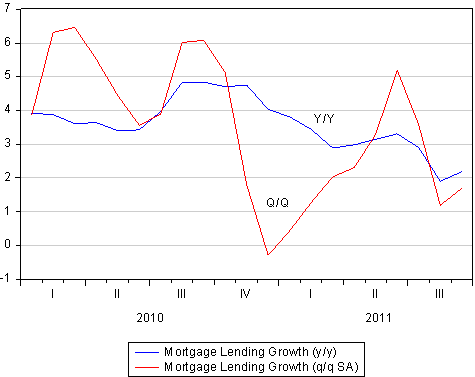

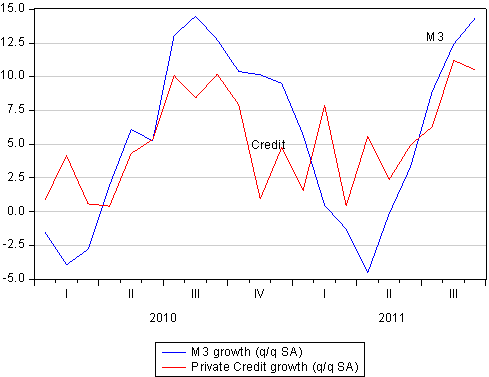

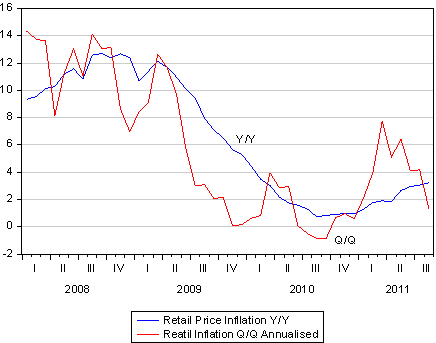

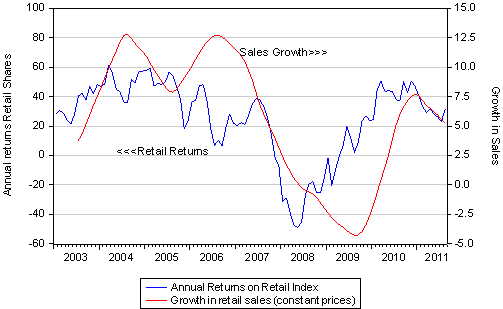

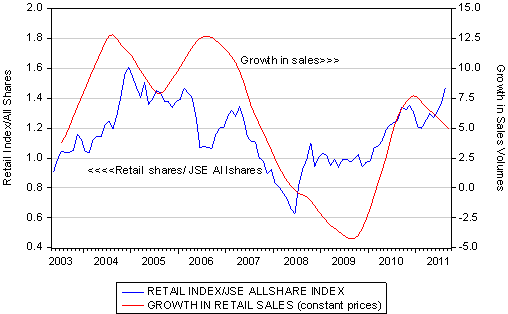

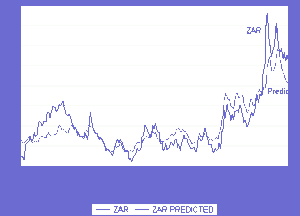

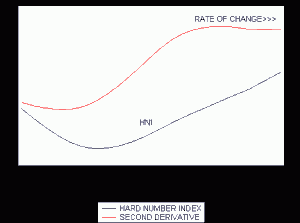

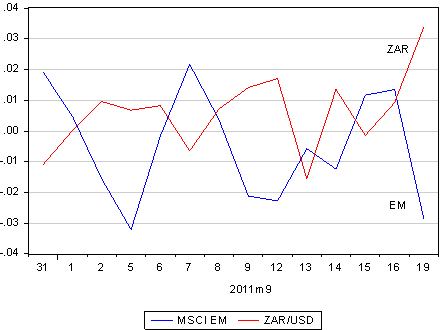

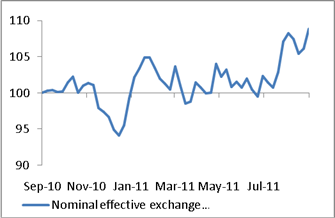

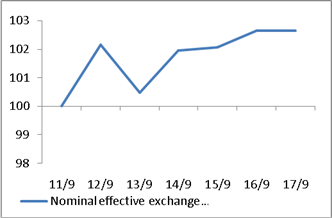

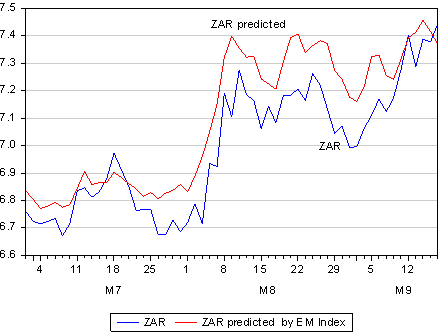

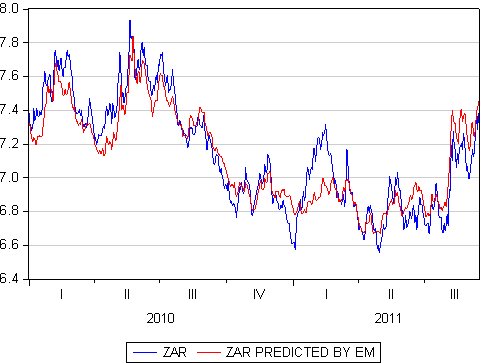

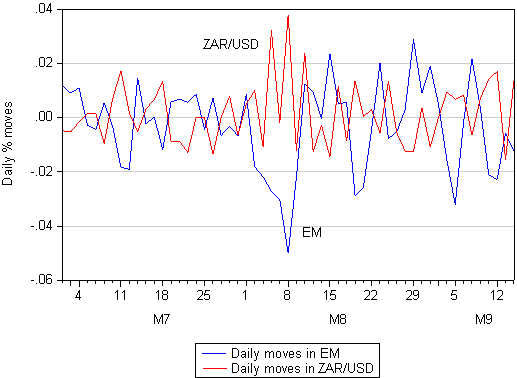

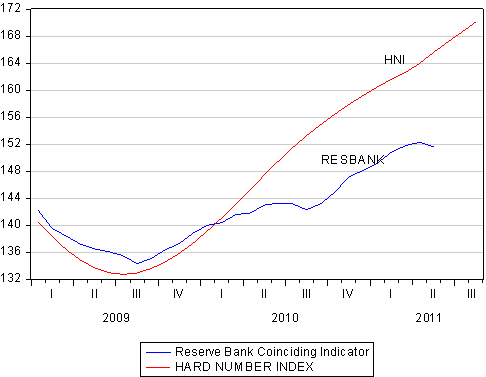

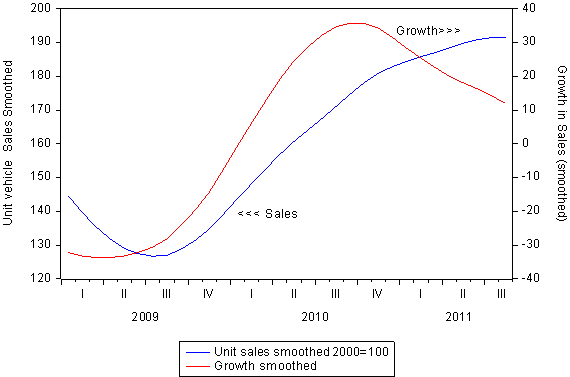

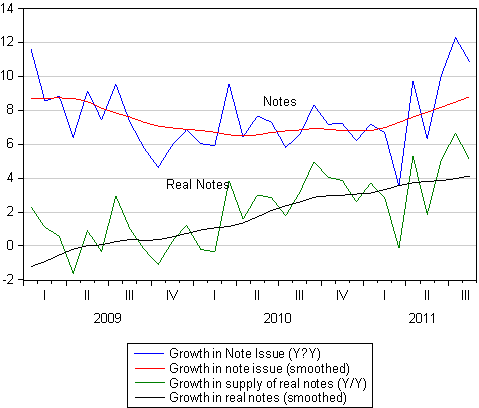

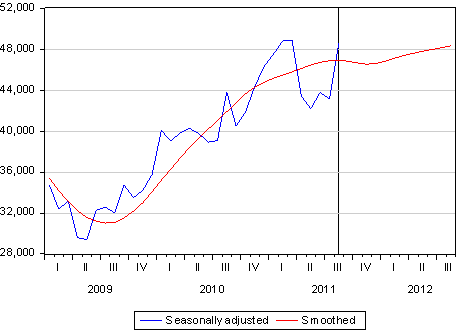

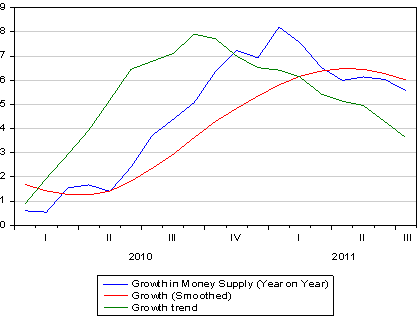

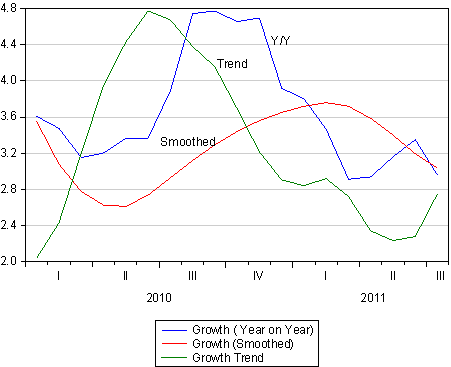

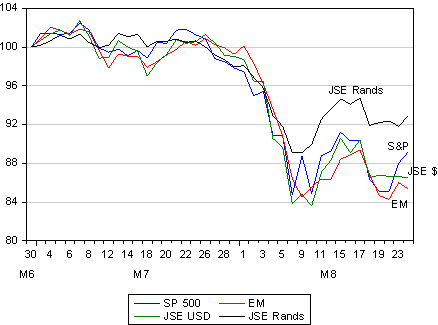

However the rand has not regained the ground it was losing at the time of its last meeting and so the SA inflation outlook will not have improved. Our sense as we have reported from retail and vehicle sales and the growth in cash, is that the local economy has picked up some momentum, even as the global outlook has deteriorated. But any incipient recovery has not been rapid enough to suggest that the gap between actual and potential GDP growth will have closed in any significant way. The housing market in SA has not shown any signs of a recovery in demand or house prices – meaning accompanying weakness in bank lending and, more important, construction activity and the employment that comes with construction and the renovation of homes.

Thus the case for lowering the repo rate is as strong as it was. The question is whether the MPC have had time to gain courage and take the leap to lower interest rates. As indicated such a leap will not come as a complete surprise to the market place.

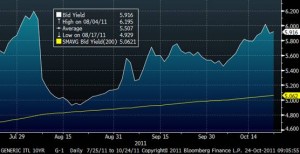

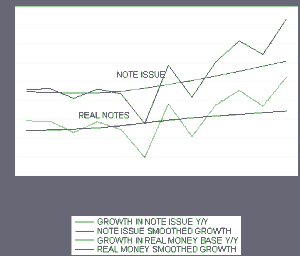

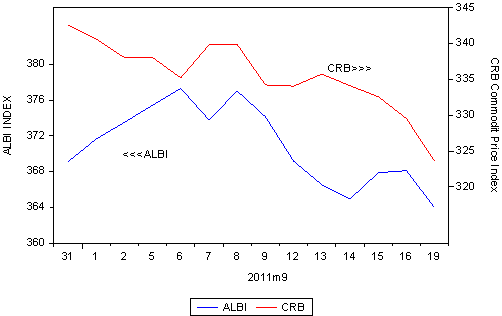

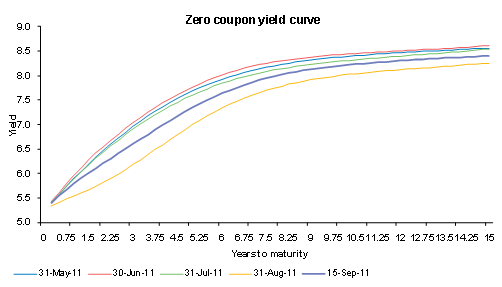

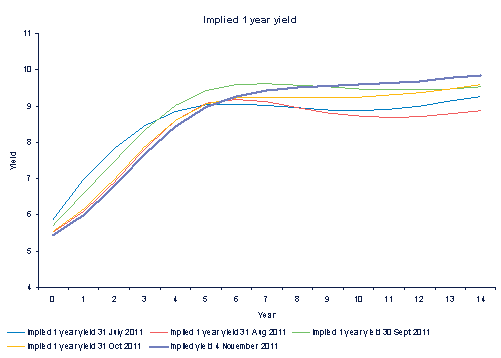

The outlook for interest rates over the longer term has also changed to a degree. Implicit in the term structure of interest rates is that one year rates will now be lower than previously thought until year five and to be higher thereafter. The yield curve is accordingly steeper – lower interest rates for now but higher over the long term.

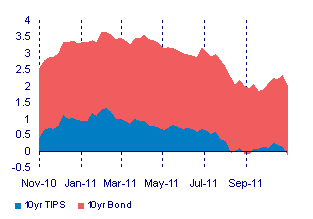

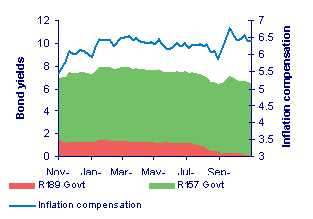

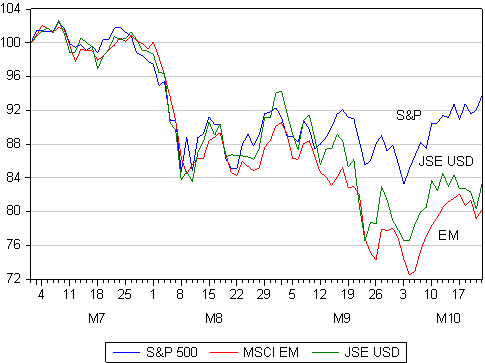

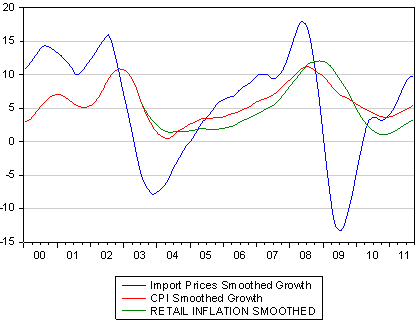

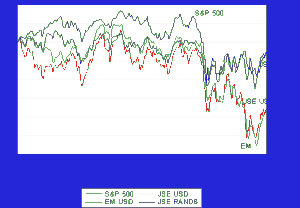

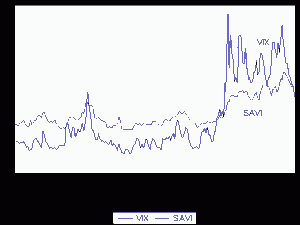

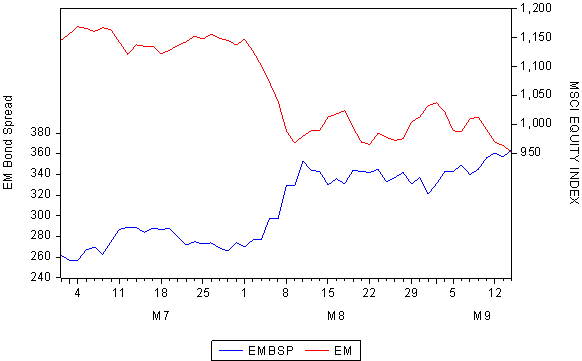

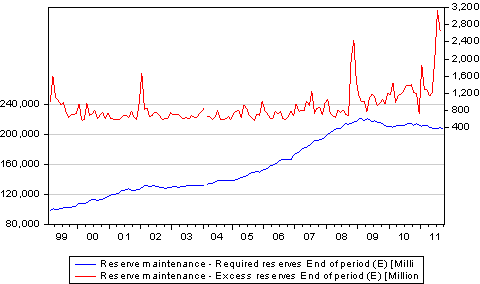

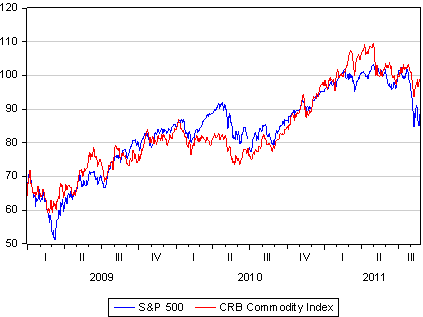

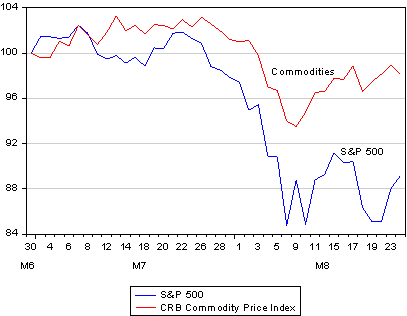

This also indicates that the market expects inflation to rise rather than fall over the next 10 years. And so investors in SA, as elsewhere, are prepared to pay up for insurance against higher inflation in the form of accepting much lower (even negative) yields on medium dated inflation linked bonds. The yield on the key 10 year inflation linked US bonds (TIPS) has turned negative again while the benchmark inflation linked RSA bond (the R189) that matures in March 2013 now offers a minimal 5bps yield – meaning that investors are being offered an extra and seemingly attractive 6.5% a year to carry inflation risk over the next few years. The bond market in the US is indicating that over the long term inflation will average about 2% a year. Given all the cash pumped into the US monetary system, but now idle on the balance sheets of banks, and all the cash pumped into and still to be pumped into the European banks, there must be a wide distribution of possible inflation outcomes about this benign 2% average. Hence the low inflation linked yields and the high price of gold (and also by comparison with lower interest rates, both real and nominal, the relatively low costs of entry into equity markets).