The economic problem is usually one of unlimited wants and highly limited means to satisfy them. It is a supply side problem that only improved productivity and improved access to capital or natural resources can ameliorate.

Economic growth sustained over the past 200 years or so has helped many to overcome the economic problem, at least to a degree. When obesity rather than starvation becomes the major danger to individual well being in the developed economies considerable economic progress has been made.

But sometimes the economic problem becomes one of too little spending rather than of dismal constraints on spending. Too little demand is now the major problem in many of the developed economies and also for us in SA. Given the current availability of labour, plant and equipment in the US, Europe and SA, more goods and services would be produced and more income would be earned in the process of expanded production, if only economic agents would spend more. More spending is thus possible without the usual trade-offs and choices having to be made between one kind of spending or another. There is no opportunity cost to employing more resources when they are standing idle.

It was a severe lack of demand that severely afflicted the US economy and other economies in the 1930s. The US economy nearly halved its size between 1929 and 1933 and economic activity had not recovered 1929 levels by 1939. These catastrophic economic events gave rise to what has come to be known as Keynesian economics, named after the famous English economist John Maynard Keynes. Keynes in the late 1930s had persuaded much of the economics profession to agree that in the absence of sufficient demand from the private sector (firms and households) governments should fill the gap between potential and actual supply of goods and services by spending and borrowing more. In other words, he argued for expanded fiscal deficits to stimulate demand when aggregate demand was painfully lacking.

Keynesianism today

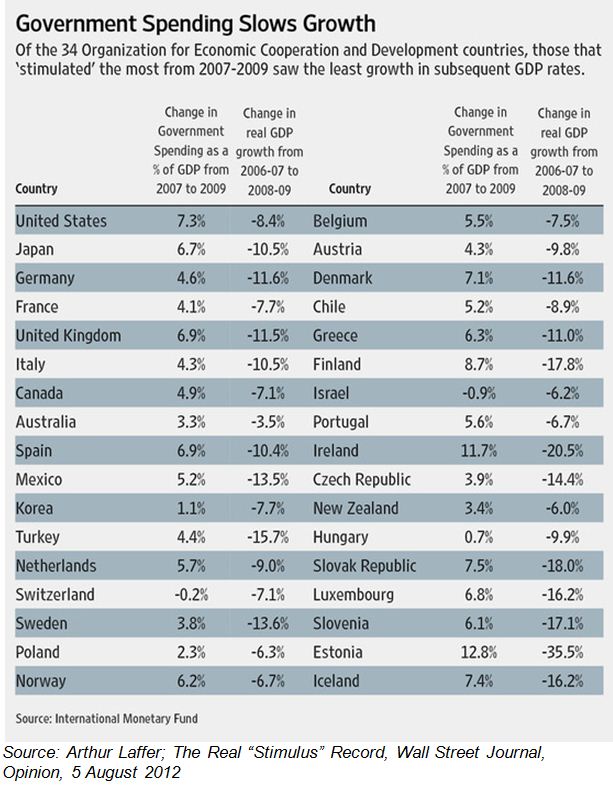

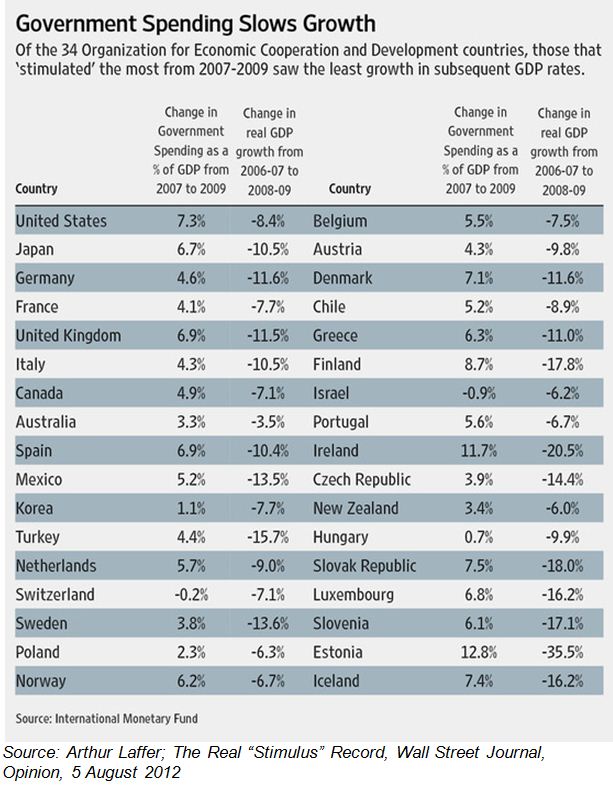

Such arguments are being made today, most prominently by Nobel Prize winning economists Paul Krugman and Joseph Stiglitz. They argue against the austerity apparently being practised by the US and European governments or recommended for them. In fact the fiscal deficits of the US and UK have widened enormously, and more or less automatically, as government revenues declined with the recession and as government spending, including spending on bailing out banks and other financial institutions, increased. But whether the larger deficits or higher levels of government spending helped to stabilise their economies, as the Keynesians predict, is not at all obvious. Arthur Laffer, in a recent Wall Street Journal article, argued that the opposite has in fact happened: that the stronger the growth in government spending, the slower the growth in GDP. He presented the following table linking changes in government spending to declines in GDP growth as evidence for this:

The UK, US, Germany and Japan, despite increased spending and larger deficits and borrowing requirements, have enjoyed one great advantage not available to Greece, Portugal, Ireland, Spain and Italy. The cost of borrowing, even of issuing very long term loans in the US, UK and Germany, has come down dramatically while the interest rates charged to Spain and Italy have risen enough to threaten their fiscal viability.

In contradiction to the Laffer evidence, it may be argued that growth would have been even slower without these increases in government spending. In the case of the Krugman-Stiglitz arguments for less, rather than more UK austerity, there is no way of knowing with any confidence what might have happened to interest rates in the UK in the absence of intended austerity. Higher interest rates would have severely further limited spending by the private and public sectors in the UK, had borrowing costs been forced higher by nervous investors in UK gilts.

The limits to government spending

The essential criticism of the Keynesian approach to recessions is that governments can only ever account for a portion of total spending. Increased spending by the public sector may well be offset by lower levels of spending by households and firms fearful of the impact of extra government spending and borrowing on their own financial welfare.

Higher interest rates associated with more government borrowing may crowd out private spending Higher taxes that will be expected to levied in the future to cover interest to be paid on a much enlarged volume of government debt may induce more private savings. Households and firms may seek to protect their own balance sheets and wealth that they believe may be subject to higher levels of taxation.

The potential limits to the ability of governments to increase total spending and the danger that firms and households and other government agencies may spend less, can be illustrated by reference to the US GDP statistics and Budget.

Of the US GDP of nearly US$14 trillion in 2011, spending by all government agencies, Federal, state and municipal governments on consumption and investment amounted to $3 trillion or 21% of GDP. Of this spending the Federal government accounted for but $1.14 trillion or about 38%.

Even when government spending is a large proportion of GDP, a high percentage of this is in the form of transfers to households and firms. So spending decisions are in the hands of these households and firms, who might feel constrained for the reasons outlined above.

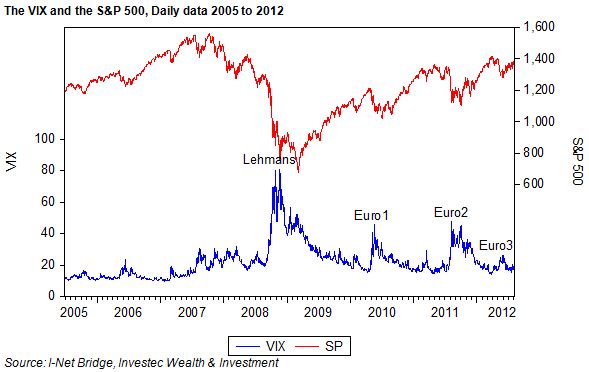

Normal times would have meant no need for QE 1, 2 or 3 or for the very low interest rates that have accompanied QE (quantitative easing). The collapse of Lehman Brothers in September 2008 threatened to bring down the US banking and financial system. Flooding the system with liquidity (cash created by the Fed) is the time honoured method of preventing a financial implosion. The great free marketer and anti-Keynesian, Milton Friedman, with Anna Schwartz in their monumental work Monetary History of the US, had accused the Fed failing to respond in this way in 1930 and by so failing in its mission, allowed a preventable financial crisis to become an economic crisis of disastrous proportions. This was not a mistake Ben Bernanke (well versed as he was in monetary history), was going to make as head of the Fed.

What about the liquidity trap?

But the Bernanke-led Fed, having avoided a financial implosion, is faced with a problem that both Keynes and Friedman were very conscious of. Keynesians wrote of the dangers of a liquidity trap: that cash could be made freely available to the banking system at very low interest rates by the central banks; but if the banks were reluctant to lend and its customers reluctant to borrow or spend, the cash would get stuck with the banks or the public. The system could fall into the liquidity trap and so lower interest rates or increases in the supply of cash would do little to stimulate economic activity.

Keynesians then call for government spending. Friedman and Bernanke in their writing called upon a hypothetical helicopter to by-pass reluctant banks to spread cash around, which would be spent to help the economy recover. Bernanke came to be known disparagingly as helicopter Ben for this idea. The trouble with helicopter-induced money creation is that it would have to be sanctioned by Congress – it would have to be included in the Budget as fiscal policy. This makes it a highly impractical response.

Given an inability to force co-operation from banks to inject cash and spending into the system, the Fed and the European Central Bank have to rely on monetary policy. They would thus continue to make cash available to the banking system and to engage in QE, so keeping the financial system afloat, and to hold interest rates as close to zero for as long as it takes, until confidence and entrepreneurial spirits revive. Moreover, Bernanke has been lecturing politicians on the need to exercise fiscal propriety to help restore business and household confidence. Brian Kantor