A crisis of poor returns on capital invested and declining employment opportunities

SA mining is in crisis. And the travails of SA mining, more particularly those of gold and platinum mining are having a very negative impact on GDP and expected GDP growth and on the value of the rand. To survive as viable businesses able to cover their costs of capital the mines have to plan for lower costs of operations and that means to plan for lower levels of production and employment, that is plan the closing rather than the opening of mining shafts. Investors in the industry and in the South African economy are not at all sanguine about the prospects for the industry and this lack of confidence is well reflected in the market value of the mining companies and in the exchange value of the ZAR.

The market fears further disruption of mining output by uncooperative trade unions. Union leaders do not appear to share the same sense as have shareholders and potential investors have of an industry in crisis. The Unions are expected to further resist retrenchment of their members and to continue to demand what shareholders and also the government regard as hopelessly unrealistic demands for improved employment benefits.

The future of deep level mining in South Africa may well lie in much higher levels of automation. This is a course of action not suited to an economy with so many unemployed or employed on far inferior terms outside the mining sector.

The mining sector contributes much to exports and to the outlook for the rand and interest rates

Lower levels of mining production, particularly if they are the result of strike action, threaten the trade account of the balance of payments and justify a weaker rand. The weaker rand then implies more inflation that makes it harder for the Reserve Bank to offer relief to the economy in the form of lower interest rates, relief, absent a widening trade deficit, that would make every economic sense.

Growth in Domestic Expenditure (GDE) has held up significantly better than growth in domestic output (GDP) meaning stronger growth in imports than in exports. The failures of the mining sector to produce more and to take advantage of what has been until recently, highly favourable price trends ( as we will show below) are a large part of the explanation of current rand weakness and slow economic growth generally.

The share market doesn’t expect growth in output or even growth in earnings and dividends from the mining houses and their subsidiaries. It is rather demanding that the mining houses pay much closer attention to cost control and operational excellence. These low market expectations should act as a warning to managers, workers and the government responsible for mining policy. The lower profits and reduced growth expected is not in synch with demands for higher wages, electricity prices and government interference with mining rights and the taxation of mining profits. The potential upside for shareholders is that if these low expectations can be countered by sober management and better relations with labour and government then these mining companies stand a stronger chance of recovering their status with investors. Merely sustaining the output of gold, platinum even at lower planned levels, would be surprisingly good news and likely to be well received in the share and currency markets.

How dependent then is the SA economy on the mining sector? It all depends on how the share is measured

The SA economy remains highly dependent on the export of minerals and metals. Directly exported minerals and metals account for as much as 60% of all export revenue. Hence the sensitivity of the foreign exchange value of the rand to mineral and metal prices and their production.

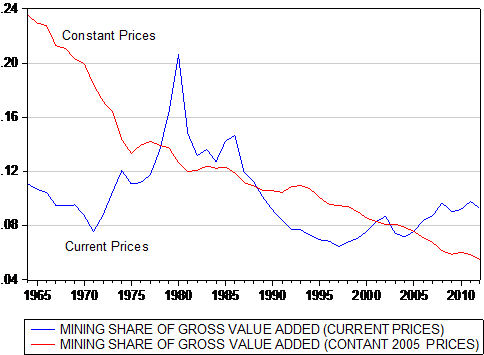

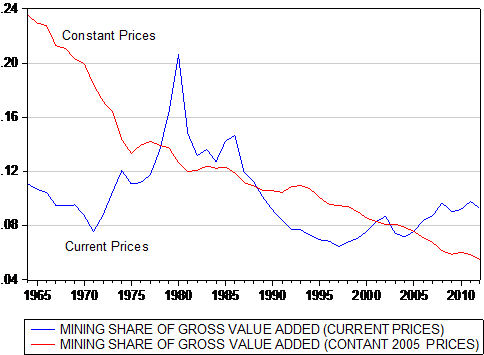

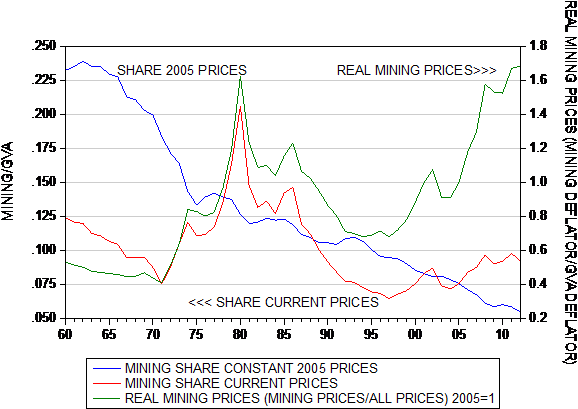

Mining’s share of the Gross Value Added (GVA) by all sectors of the SA economy in 2012 was no more than 5.5% when measured in constant 2005 prices. When both mining output and GVA, including mining output, is measured in current prices, mining’s share rises to 9.3% of GVA. As we show below, when measured in constant 2005 prices, the contribution of mining to GVA and GDP has been steadily declining over many years from a large 23% share in 1960 to the current less than 6% share , regardless of the direction of global metal and mineral prices and so mining revenues.

As we also show that when the share of mining is measured in current money of the day prices the share of mining in the economy takes on a very different complexion. The share of mining in the SA economy, so measured as a ratio in current money of the day prices, was less than 12% in 1960, compared to over 23% in constant price terms that year. In 1970 the share of mining in GVA was 8.8% if measured in current prices, or a much higher share, 20% of the economy, if measured in constant 2005 prices. Thereafter the mining share measured in current prices rises significantly rises in response to the very significant increases in the gold price in the seventies. When the gold price peaked in 1980 the share of mining in GVA in current price terms was as much as 21%- but then only about 12% if recorded in constant 2005 prices. Thereafter, as the gold price fell away and the prices of mining output were subject to a long period of deflation and a further decline in the output of gold, the share of mining in current price terms fell further to a much less important 7% by the year 2000. Thereafter when measured in current prices Mining gained a marginally larger share of the economy to the 9% share measured in 2012. The increased output of and higher prices coal and iron ore were significant contributors to thei increase in economy share. The share of mining in the economy in constant price terms by strong contrast declines continuously after 1960 and appears completely unaffected by relative prices or industry trends as we show below.

The share of Mining in Gross Value Added using constant 2005 prices or current prices

Source; SA Reserve Bank Data Bank, Investec Wealth and Investment.

Real prices matter a great deal to producers

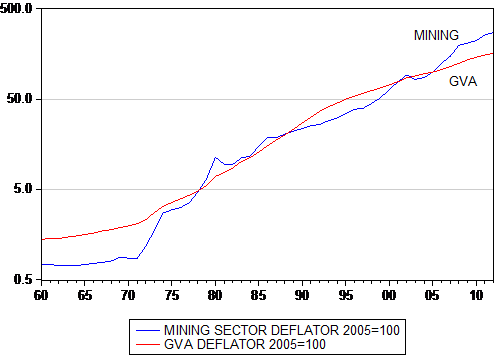

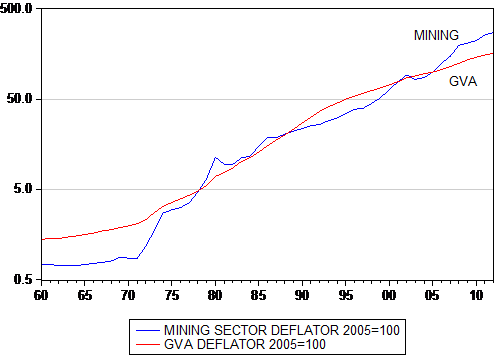

A key to the role of any sector of the economy, with an improving or deteriorating share of the economy, is surely relative price trends. When a sector enjoys what may be called pricing power, that is to say the sector can price increases ahead of the average rate of inflation , then one would expect improved profit margins to follow and extra output to be encouraged. In the figure below we show how the SA Mining Sector Price Index, that is the mining sector deflator, has compared over the years with all prices, including the prices of metals and minerals, as reflected by the Gross Value Added Deflator.

As may be seen between 1960 and 1970 Mining Sector selling prices lagged well behind the selling prices of all SA production or value Added. In the seventies, helped especially by a rising gold price, prices realised by the SA mines, rose significantly faster than prices in general. A long period of metal and mineral price deflation then followed until approximately 1999 when commodity prices picked up strongly in absolute and relative terms. These favourable trends or terms of mining trade were then disrupted by the Global Financial Crisis of 2008-09

The Mining Sector Deflator compared to the Gross value Added Deflator (2005=100) Logarithmic Scale

Source; SA Reserve Bank Data Bank, Investec Wealth and Investment.

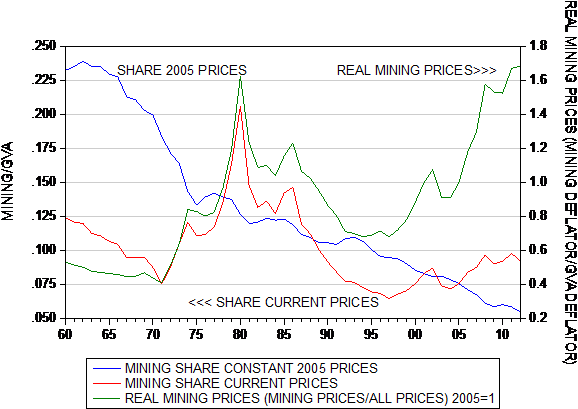

If we divide the Mining Sector deflator by the GVA deflator we get the relative price of mining output. For producers in any sector the higher the relative price the better and the more encouragement offered to increase otput.[1] In the figure below we compare these relative prices with the share of Mining in GVA, measured in current prices. As may be seen the share of mining grows and declines very consistently with improvements in or a deterioration of the relative prices of mining output. Such responses make every economic sense. That the share of mining, when measured in constant price terms, declines consistently and independently of these relative prices makes very little intuitive sense. Relative prices appear to make no positive impact on the mining sector at all when the mining share is measured in constant prices. The share of mining in the economy, when measured in constant prices, simply declines continuously as may be seen.

The reason for this highly counterintuitive result is simply in the arithmetic of National Income Accounting conventions. If sector prices – for example mining sector prices – rise faster than prices in general then the share of that sector in the economy, when measured in constant prices, automatically declines and vice versa when sector prices rise more slowly than prices in general the share of that sector will rise automatically. [i]

The presumption of such a result is that it is the supply side of the economy, rather than demand forces that drive relative prices and so relative shares in national income methods of calculation. That is it is an increase in supply that results in a lower relative price and so a larger share of the economy. Rather, that as in the case of mining output, where prices are set globally and the mines are price takers, to presume that it is an increase in global demand that leads to higher prices and in turn to more profitable production and so increases in output and in the share of the economy realized by a sector.

Applying the standard convention to the share of Mining and also Exports in SA subject to similar price trends becomes seriously misleading. Measuring sectoral shares using current prices makes much more economic sense.

It should be noticed in the figure below that SA miners benefitted from an extraordinary increases in the prices for their output compared to prices in general in the seventies and after 2000. Relative prices have moved further to the advantage of the mining sector over the past twelve years as may also be seen. That Mining’s share of the economy did not rise anything like as significantly in the past decade and more reflects the wasted opportunity to benefit from the commodity super cycle. The mining boom in terms of volume of output produced regrettably largely passed South African production by. The costs of mining gold and platinum rise as rapidly as did prices. Uncertainties about government policies towards mining and the failure to invest in additional transport infrastructure to export more coal and iron ore also contributed significantly to the modest supply side responses to much more favourable relative price trends.

Mining share of GVA and Relative Mining Prices

Source; SA Reserve Bank Data Bank, Investec Wealth and Investment.

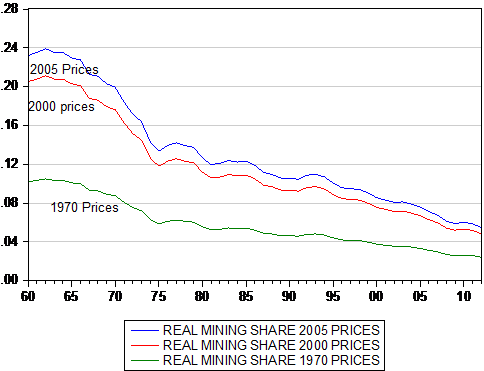

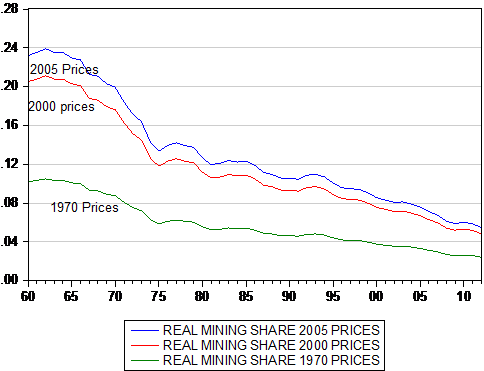

Another very good reason to question the use of constant prices to calculate sectoral shares of the economy is that these shares can change meaningfully with changes in the base year used to measure constant prices. Using exactly the same price series, the same deflators, measured in constant 2005 prices or constant 2000 or constant 1970 prices can make a large difference to the share of a sector measured in constant prices as we show below. Using a deflator with 1970 prices =100 for both Mining and GVA, to one using much lower 2000 prices or 2005 prices as the base equal to 100 shifts the share of mining in constant prices in 2012 from 2.4% using 1970 prices to 4.8% using 2000 prices to 5.5% using 2005 prices. [ii]

Share of Mining In the SA economy using different base years

Source; SA Reserve Bank Data Bank, Investec Wealth and Investment.

That changing the base year can have such a meaningful effect on the sector share makes the use of constant prices as the basis for calculating the share of different sectors in the economy highly unsatisfactory. While the trends in the sector share, measured in constant prices using different base years, remains exactly the same the numerical values can turn out to be very different. Every change in the base year results in once and all constant shift in the trend giving a different impression of the importance of the sector to the economy. This is why in our judgment the most consistent measure of mining’s contribution is the ratio of mining output to Gross Value Added ( GVA)when both mining output and that of all sectors including mining GVA, is measured in money of the day prices. By this calculation the share of mining in the SA economy peaked in 1980 at over 20% and currently contributes about 9% of all value added as we show above.

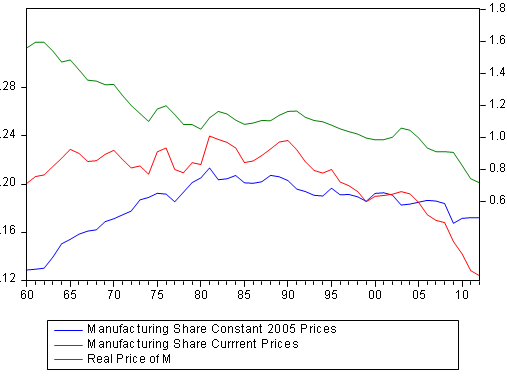

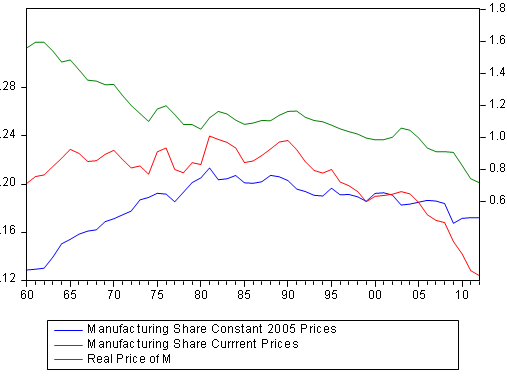

The contribution of manufacturing to the SA economy is exaggerated using constant price calculations

The same approach to measuring the share of Manufacturing in SA production can be taken. In the figure below we show Manufacturing’s share in GVA as well as the relative price of manufacturing Output. As may be seen the share of Manufacturing measured in current prices was approximately 24% in the eighties. It has since declined markedly to a 12.4% share in 2012. This declining share has been accompanied consistently by an almost continuous decline in relative prices. This downward price pressure has clearly accelerated in recent years. Manufacturing in SA has become increasingly exposed to competition, especially from abroad. Consumers and retailers and their employees have benefited from the competition.

Manufacturing Sector; Share of Output and Relative Prices

Source; SA Reserve Bank Data Bank, Investec Wealth and Investment.

Conclusion

Economic statistics should accurately reflect economic realities and hopefully lead to appropriate economic policy and policy changes. Measuring sector shares in SA in constant price terms as is the National Income Accounting Convention is very misleading about the role of mining in South Africa and therefore also about the role of other sectors, including Manufacturing as we have argued. A irony is that if shares in the economy were measured in current rather than constant price terms this past quarter the disappointing and currency moving Q1 GDP numbers would have looked rather different. Manufacturing, with a lower share of the economy when measured in current prices, 12.3% share in current prices in 2012 compared to 17.2% in constant prices, with a close to 8% decline in output on a seasonally adjusted and annualized basis, would have been less of a drag on economic growth. And mining output that increased in Q1 given a larger share of GVA (5.6% in constant prices, 9.3% in current prices) would have added more to the growth rate.

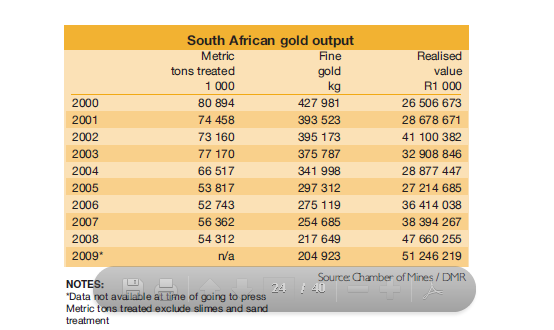

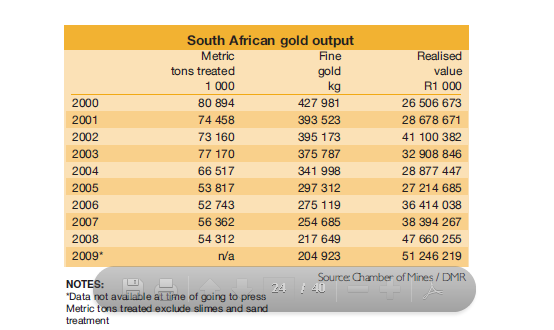

[1] The case of Gold Mining in South Africa is somewhat different to the norm. In the seventies and eighties the higher gold price offered a choice to the mines. They could choose to mine shafts with lower grade, that is ore with lower gold content and in this way extend the life of the mines by extracting more gold bearing ore so leaving less gold behind. They typically elected, where possible, to extract more gold bearing ore from underground with lower average gold content. As a result the output of gold fell from 1000 metric tons in 1970 to 670 tons in 1985 while the tones of ore extracted and milled by the mines grew by about 30% from 75m tons in 1970 to 105m tons over this period 1970 – 1985. Capital expenditure by the gold mines was R106m in 1970 and R1911m in 1985. Working profit per ton of ore milled was a marginal R3.9 in 1970 and a hugely profitable R70.46 in 1985. 416,846 workers were employed by the gold mines in 1970 and 513,832 in 1985. If productivity was measured as output of gold per worker employed then it declined sharply over this period, from 2.3 kg of gold per worker in 1970 to 1.3kg in 1985. If productivity was however more realistically measured as tones of ore extracted per worker, then it would have improved from 178 tonnes of ore milled d per worker in 1970 to 203.5 tonnes in 1985. These tradeoffs of lower grade for a longer mining life seem no longer available to the gold mining industry. The better grades of ore appear as largely exhausted and the industry is forced to mine lower grade ore at ever deeper more costly levels. The volume of ore extracted has declined consistently over the past ten years while the annual output of gold from SA mines is now below 200 tonnes. (See Table Below) Source; Annual Reports of Chamber of Mines of South Africa.

[i] The mathematical proof of this and other propositions made here are to be found in a paper written in 1987 with Iraj Abedian, Relative Price Changes and their Effects on Sectoral Contributions to National Income , that can be found in my blog www.zaeconomist.com

[ii] Reducing or increasing the absolute value attached to the price series reduces or increases the sectoral share by a constant value. The 1970 deflator rises from a very low absolute base of 100 in 1970 to a level of close to 50000 in 2012- a 500 times increase in average prices over the 42 years. The deflator for 1970 using 2005 prices as the basis would have an absolute value of 0.869 compared to the value of 100 if 1970 was chosen as the base year. Clearly such absolute numbers with excatly the same underlying trend should not have a real effect.