Introduction

In this report we explain why quantitative easing has been called for in the US because the demand by banks to hoard cash has increased so dramatically despite lower interest rates. This demand for cash has meant less bank lending and a weaker economy. In South Africa the unwillingness of banks to lend has also to be countered for the sake of the economy. However the monetary problem locally, unlike the US, is the slow growth in the supply of cash rather than the increase in cash hoarded at he Fed. We call for a combination of lower interest rates and quantitative easing to revive bank lending and the SA economy

Lower interest rates may not work if banks prefer to hoard than lend cash

It is clear that reducing interest rates cannot on their own always revive an economy in recession. Central banks in the US and Europe have become ever more ready to freely assist their member banks with cash at close to zero rates of interest. But the private banks have remained unwilling to borrow the cash. They have preferred to lend more to their central banks rather than borrow from them.

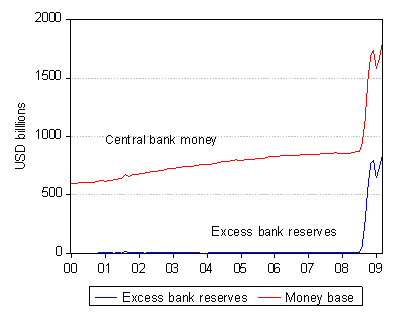

As we show the US banks have come to hold cash reserves far in excess of their legal requirements to do so and this demand for cash has greatly inflated the supply of central bank money in the US being the sum of the notes issued by the Federal Reserve Banks plus the deposits of the bans with the Fed less the cash held to meet compulsory reserve requirements.

US central bank money and excess cash reserves of the banking system

Source; Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis and Investec Securities

Source; Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis and Investec Securities

The banking system is powering down rather than up

This sum of central bank money is sometimes described as the money base of the system or more evocatively as its high powered money. This description indicates that increases in central bank money usually power up the supply of bank deposits in the system that are included in the broader definitions of the money supply (M1, M2, M3) But this can only happen when the banks lend out the cash. When the banks hoard the cash the system powers down rather than up as it is now doing.

Thus quantitative easing

Hence the call for quantitative easing to get the cash on the balance sheets of the central banks back into circulation so that it can help stimulate more spending as extra money normally does. The central banks eases quantitatively by utilising the cash it has on deposit to buy assets in the money and credit markets. This exchange of cash for assets, usually for securities issued by the government itself or government supported agencies, gets cash in the hands of those – unlike the banks – who are more likely to spend or lend rather than hoard cash. Judged by the recently improved ability of US and European companies to raise capital in the money, bond and lately also again in the equity markets, it does appear as if the global credit system is easing up in a most welcome way.

Both the supply of and demand for money matters

Recent developments in the money markets helps to remind us that what matters is not so much the supply of money but the excess supply of money, that is the excess of the supply of money over the demand to hold money. When the supply of money grows faster than the demand to hold more money the extra spending then pushes up prices at a faster rate. And when the supply of money lags behind the demand to hold money you get the opposite – less spending and deflation. This is the problem for the developed world- the demand to hoard money has grown even more rapidly than the supply of money. The challenge central bankers will face in due course will be to reign in the supply of cash when the banks become more willing to lend and less anxious to hoard their cash.

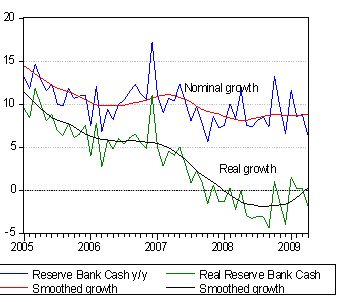

In South Africa the supply of money is growing far too slowly

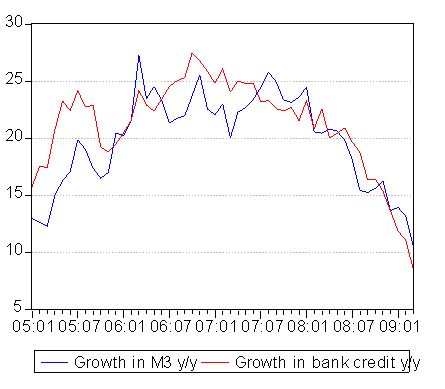

While the SA economy is also performing well below its potential completely opposite conditions prevail in the money market. Unlike the case abroad, the growth in the supply of SA Reserve Bank money has been growing very slowly and far too slowly for the health of the economy. (See below) As we also show the growth in the supply of more broadly defined money, to include deposits issued by the commercial banks, has been decelerating sharply, as has the growth in the supply of bank credit to the private sector. The growth in M3 that was over 25%

in mid 2007 is now running at about 10% pa as may be seen in the figure below. However this growth rate understates the recent sharply decelerating trend in the growth in money and credit. The March 2009 quarter to quarter seasonally adjusted rate of growth in M3 was but 6% and the growth in bank credit supplied to the private sector was but 2%. Clearly these growth rates are far to slow to help revive the SA economy.

Growth in SA Reserve Bank Cash Supply

South Africa; Growth in M3 and Bank Credit supplied to Private Sector

No banking crisis in SA – merely an economic crisis not helped by nervous banks. Quantitative easing called for

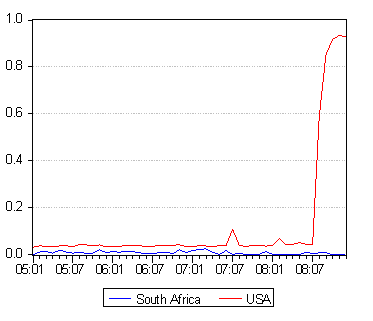

South Africa has not suffered from a credit or banking crisis. Banks in South Africa, unlike their US peers have therefore not increased their demand for cash reserves. The ratio of excess reserves to the supply of central bank money remains very close to zero as we show below.

USA and South Africa- ratio of excess to required cash reserves of Banking System

But the SA economy is growing far below its potential. SA banks too are suffering from higher write offs for bad debts though nothing like the scale infecting the banks in the US. Yet much more important they too have become more reluctant to lend and this is adding to the weakness of the economy. Something therefore needs to be done to accelerate the growth in the supply of money and credit in SA . Lower repo rates, still far higher than levels in the developed world, may not be sufficient to the purpose. Quantitative easing in fact is as much called for in South Africa as it is the US to encourage the banks to lend more.

How best to ease quantitatively

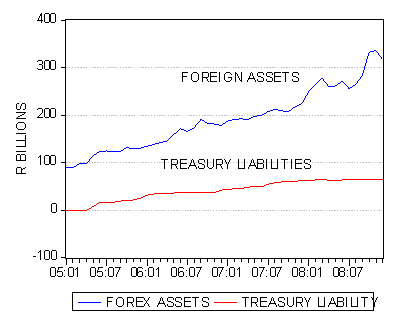

The method to do so is at hand. That is for the Reserve Bank to counter unwanted rand strength with purchases of foreign currency. However the additional rands, used to pay for the foreign currency, should be allowed to a greater degree to find their way into the market rather than be sterilised by the Treasury. Such sterilisation operations have taken place on a large scale in recent years to counter the growth in the foreign exchange and gold assets of the Reserve Bank. The Treasury has borrowed large sums, some R66b at year end to this purpose. The funds raised are then kept idle at the Reserve Bank and these idle balances then reduce the cash available to the private sector and prevent the money supply from increasing.

SA Reserve Bank

Given the increase in the fiscal deficit and the ordinary borrowing requirements of the Treasury the idea of selling fewer interest bearing government bills and bonds for the purpose of restraining the growth in the cash supply should have additional appeal. The case for encouraging the supply of cash to grow faster in SA has become a very strong one. The SA economy needs both lower interest rates and quantitative easing to recover its growth momentum.

If you want to do a cash advance from an ATM, you will need to set up a PIN # with the crdeit card. You can probably do that online. You should be able to go inside the bank and use the card for a cash advance without a PIN.When you take a cash advance on a crdeit card, there is a transaction fee, usually 3% to 5%. Interest is usually at a higher interest rate than purchases and the interest starts to accrue immediately. A cash advance can be pretty expensive.Most crdeit cards offer interest free grace periods from the date of a purchase to the statement due date, if you pay the full balance on your account. This interest free grace period does NOT apply to cash advances. The interest starts immediately. You still can make monthly payments to pay off the advance.