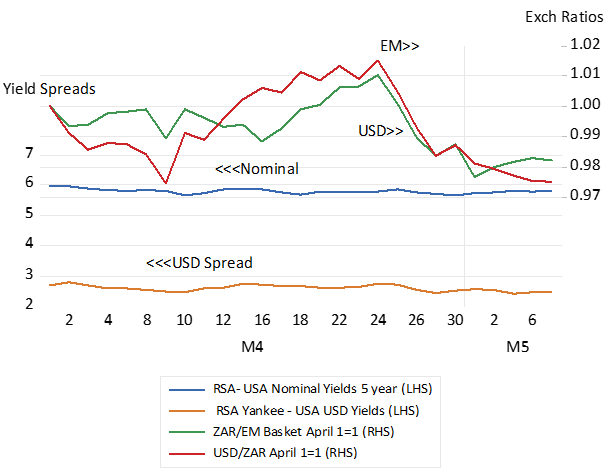

There is a confident calm in the SA financial markets despite the upcoming election the outcomes of which are surely uncertain. Since about two weeks ago the premium for accepting the risk of a SA debt default, measured as the spread between the yields on RSA dollar denominated debt and USA Treasury yields, narrowed marginally to 2.5% p.a by May 7th. It was 2.71% on April 25th. The spread between RSA and USA 5 year bond yields, has remained stable though it is still a discouragingly wide 5.8% p.a. as US and RSA interest rates moved lower off recent highs. Very recently the US dollar has become a little less expensive and value of the ZAR has improved when exchanged for other EM currencies, both by about 2% between since April 25th – which appears as the recent turning point in sentiment – and May 7th

Interest rate spreads and exchange rate ratios. April – May 2024- Daily Data

Source Bloomberg and Investec Wealth & Investment

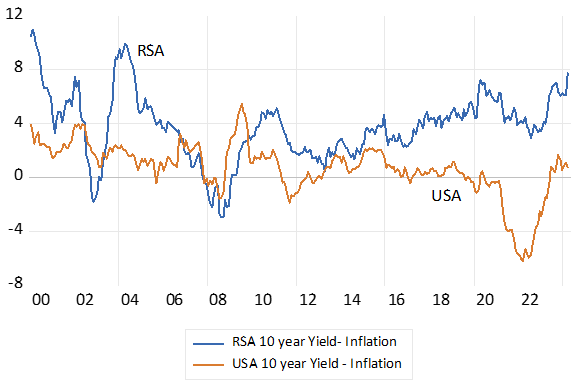

Interest rates, by themselves, tell us little about the rewards for saving or the cost of borrowing. It is after inflation interest rates, that reflect the real rewards for saving and the real cost of issuing debt. Real rates have declined with inflation in the developed world since the mid-eighties. Post covid the long decline in real and nominal bond yields appears to have reversed accompanied by higher inflation. Inflation and nominal and real interest rates in SA have remained comparatively elevated, even as inflation has receded. Since 2000 the real after realised inflation rate for an RSA 10 year Bond has averaged 3.7% p.a. while a US Treasury has offered on average a real less than 1% p.a. The current RSA-USA real yield gap is a large 6% p.a. for ten-year money. Making for undesirably expensive capital for the SA public and private sectors.

Real (after inflation) Long term Interest Rates in SA and the USA

Source; Bloomberg, Federal Reserve Bank of St.Louis, SA Reserve Bank, Investec Wealth & Investment

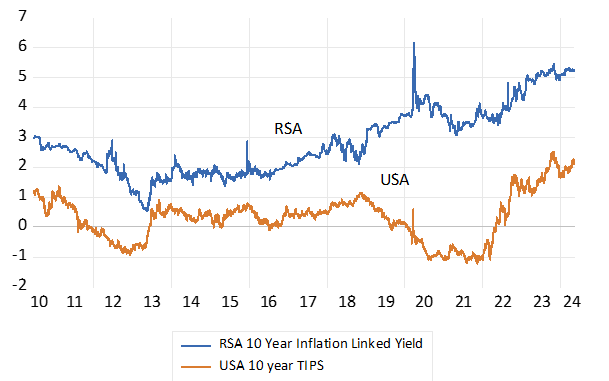

Yet with the advent of inflation protected government bonds rather than be exposed to potentially harmful, inflation events, that reduce the purchasing power of their interest income lenders can own fully inflation protected bonds. Bonds that are guaranteed to maintain their purchasing power regardless of the inflation outcomes. Since 2010 the RSA ten-year inflation linker has offered an average real 2.84% p.a. compared to an average 0.32% p.a. for the US equivalent. This real yield gap has widened significantly in recent years as RSA real yields have risen. The RSA inflation linked ten-year bond currently offer an impressive 5.3% compared to 2.1% for the US TIPS- a real spread of over 3% p.a.

Real Inflation Protected Yields in South Africa and the US. 10-year Government Bond Yields

Source; Bloomberg, Investec Wealth & Investment

Why has this high real 5.3% p.a. inflation protected yield not attracted more investor interest and a higher value? It is a rand denominated bond with no default risk- and no inflation risk. To which the equivalent vanilla bond is subject to – and to default through inflation – should control of the money supply be abandoned, as is always possible, should governments become irresponsible spenders. The current yield on an inflation exposed RSA vanilla bond with ten years to maturity is now about 12% p.a. And after inflation, if maintained around the current 5%, would become a very realised high real yield- and very comparable with the yield on the inflation linker.

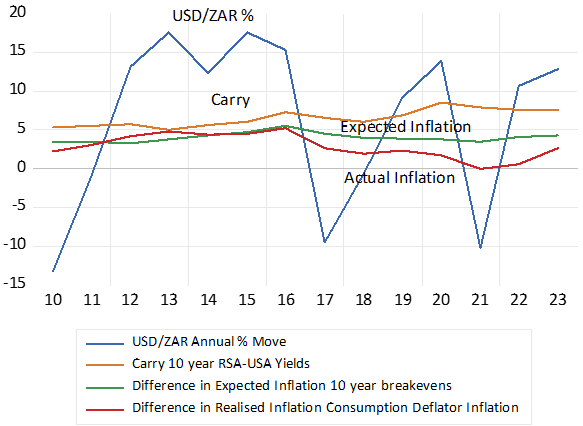

These RSA nominal and real yields are closely connected and elevated, by expectations of rand weakness. A market-based weaker expected exchange rate is revealed by the positive difference between RSA and USA borrowing costs and interest rates over all durations, from 3 months to ten years. This carry, or equivalently, the actual or potential cost of hedging rand exposure by buying dollars for forward delivery, reduces the actual or expected dollar returns on SA debt held by foreign investors. That is when they convert rand income, be it inflation protected or exposed, and capital gains in rands into dollars when exiting a trade in a rand denominated security, they will be well aware of the dangers of rand weakness. If they expose themselves to rand risks and do not hedge their exposure with forward cover, they will make a dollar profit when the rand weakens by less than the carry, that is by less than the difference in SA and US interest rates over the investment period. If the rand weakens by more than the carry they will have been better of holding the lesser interest paying, dollar denominated security.

The SA carry, the expected move in the USD/ZAR exchange rate, is however consistently much wider than the difference in actual and expected SA and US inflation. One might surmise that movements in exchange rates equilibrate differences in inflation and differences in expected inflation between trading partners. To level the foreign trading field. But this has not at all been the case. Since 2010 the highly volatile USD/ZAR has weakened on an annual average rate of a 6.3% p.a. The comparatively stable ten-year carry, the average extra cost of buying dollars for forward delivery, has averaged 6.53% p.a. while the difference between expected inflation in SA and the US, has averaged a fairly consistent 4% p.a. While the difference in realised inflation has averaged a mere 2.9% p.a. These long-term trends have made the USD/ZAR a consistently undervalued, therefore highly competitive exchange rate.

Reducing inflation will reduce interest rate levels and unhelpful interest rate volatility and real rates, as the Reserve Bank has asserted it is likely to do. But it will not necessarily make the rand more competitive as the Bank also asserts. With lower inflation the exchange rate might weaken by less than the difference in realised inflation rates between SA and in our trading partners. In which case lower interest rates and a stronger rand could well be accompanied by a less competitive exchange rate.

Interest and Exchange Rate Trends. Annual Data

Source; Bloomberg, Federal Reserve Bank of St.Louis, SA Reserve Bank, Investec Wealth & Investment

Persistently lower SA inflation and lower interest rates will therefore require not only less inflation, but less expected exchange rate weakness. That is a reduced difference between SA and US interest rates as SA interest rates fall.

How could this be achieved? A stronger rand and a stronger rand expected, and with it less inflation realised and expected, can only come with faster real growth, that would bring more favourable flows of taxes, proportionately smaller fiscal deficits and issues of RSA debt- given also restrained government spending linked closely to the same real growth trajectory. The Reserve Bank has limited influence on essential supply side reforms that would be essential to raise the actual and expected growth rates. The Reserve Bank lacks any predictable influence on the most important leading inflation indicator, the exchange rate, influenced as it is so strongly by global risk appetites as well as economic policy successes or failures. Interest rate increases at the short end of the money markets should never be used to fight rand or domestic currency weakness generally. Exchange rates should be left to market forces, and the wider spreads that accompany exchange rate weakness and the higher prices that temporarily accompany currency weakness are very hard to overcome without additional damage to the spending side of the economy. The Bank of Japan has been learning as much.

A wider or ideally a narrower carry, that is the interest rate spread between economies and currencies is part of a new equilibrium in financial markets. It reflects the adjustment to more or less perceived exchange rate risk and less or more capital supplied to a domestic financial market. It calls for the right supply side reforms that lead to faster growth and improved expected risk adjusted returns from additional private capital supplied willingly to domestic borrowers. Including to the government, the borrower that sets the level of interest rates.

The Reserve Bank as should other central banks effectively manage the demand side of the economy, so that demand, under the influence of real short term interest rates, does not exceed potential local supplies, nor fall short of them. So to avoid upward or lower pressure on prices and incomes, wage and interest incomes included. This is far from the actual state of the SA economy today. It suffers from too little rather than too much spending. The Bank could now help growth and the foreign exchange value of the ZAR by reducing what are very high nominal and real short term interest rates that have throttled domestic spending.