A PS on the fundamentals of capital raising

The past quarter has been record breaking. Records have been set in extra spending by governments measured as a share of (normal) GDP. For the developed world this additional emergency spending by governments has ranged between an extra 5 to as much as 15 per cent of GDP. Another record has been set in money created by central banks. Of the order of an extra 5 trillion dollars worth. Included in their current bout of QE have been substantial purchases of corporate debt.

The monetization of much debt has meant very low interest rates with which to fund rapidly growing fiscal deficits and rising debt to GDP ratios. Records are therefore also being set in the amount of cash raised by businesses. Since the end of March, U.S.-listed firms have raised a quarterly record beating $148 billion of extra capital. Monetary policy has made capital raising on a vast scale possible on increasingly favourable terms. And without which a strong recovery from the lockdowns would be impossible.

Loan guarantee schemes, provided to commercial banks by central banks backed up by their Treasuries, has been an important component of the financial relief promised. These loan guarantees – should they be fully required to offset defaults – which is not at all expected – are available on a very large scale. In normally fiscally conservative Germany extra government spending on relief is of the order of 15% of GDP while the loan guarantee provision is of the order of 30% of GDP. For the US the stimulus plan is equivalent to 7% of GDP with the guarantee adding another 8% of GDP to the package.

It makes every economic sense that ordinarily sound and profitable businesses in SA as elsewhere not be forced out of the economy for an inability to service or roll over their debts for reasons entirely beyond their control. And are able to start up again by recapitalising their operations – given how much capital has been lost during the lock downs

The South African economy has not benefitted from fiscal and monetary relief on anything like the scale offered elsewhere. The additional borrowing requirement of the SA government has surged to over 14% of GDP more than double the deficit planned in February as we learned from the Minister of Finance yesterday June 24th. Largely because largely because tax revenues have declined so sharply- by over R300b with further declines expected. Extra government spending on its adjusted Budget is estimated as but R36b.

Despite a relative lack of encouragement of the kind offered in the US and elsewhere to the market for corporate debt, the capital market in SA has been active. We have seen something of a flurry of capital raising by JSE listed companies. The issue of relevance to shareholders (and the banks underwriting the issues) is whether the extra capital intended to be raised can pay for itself. That is will the extra capital raised earn a return that will covers the (opportunity) cost of the capital raised. That is equivalent to the high long-term RSA bond yield of 8% plus a equity risk premium of 4% or more for the least risky of businesses- something ahead of 12% p.a. returns for the least risky of enterprises.

If the answer is a positive one a rights issue or indeed any secondary issue to raise capital or indeed debts – should go ahead. And the hope must be that the market immediately shares this justifiable optimism and re-prices the company’s shares accordingly. That is prices the businesses raising additional capital them now for more likely survival rather than extinction.

The same positive answer is required of any business large or small that needs to raise capital to resume business post-Covid. Will the essential extra capital raised cover its risk-adjusted costs? We must hope that the SA financial markets, especially the banks, can help meet these additional, calls for extra capital. The loan guarantee scheme offered by the Reserve Bank in SA is perhaps the best hope for business and economic rescue.

The government has the task of ensuring that the capital market is up to this vital task of funding both government and business on sensible terms. Without which the prospects for a post-Covid recovery in SA, absent fiscal stimulation, remain especially bleak. The burden of economic relief has passed to monetary policy.

Postscript on capital raising on the JSE

We have seen something of a flurry of intentions to raise additional capital raising by JSE listed companies. The latest by retailers the Foschini Group (TFG) and Pepkor in the form of rights issues to their shareholders. Mister Price (MPR) another retailer has also indicated an intention to raise more equity capital.

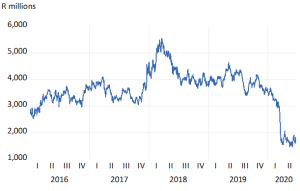

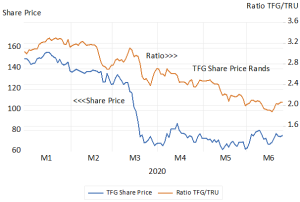

TFG announced plans on June 18th 2020 to raise R3.95b from its shareholders, equivalent to 22% of its current market value of approximately R17.5b. A market value that has shrunk by more than half this year on fears of exposure to Covid19 accompanied by a seemingly debt laden balance sheet. The market has however reacted somewhat favourably to the announcement. The share price has held up since the announcement and regained a little lost ground when compared to the Truworths (TRU) share price, a rival retailer. ( See below the figures that chart the market value of TFG over recent years and where we compare the TFG share price to that of clothing retail rival Truworths (TRU)

TFG Market Value of Company Daily Data; 2016- June 22nd 2020

Source; Iress and Investec Wealth and Investment

TFG Share price and Ratio of TFG to TRU share prices – Daily Data 2020 to June 24th

Source; Iress and Investec Wealth and Investment

The terms of the TFG rights issue (to be underwritten by a consortium of banks) will only be announced should the proposal gain shareholder approval on the 16th July. It should be understood that as a rights issue this extra capital cannot reduce the share of the established shareholders in the company, should they follow their rights. They may however prefer to sell such rights to subscribe extra capital. This benefit in selling the rights to subscribe can be regarded as compensation for giving up a share of the company’s profits and dividends and market value in the future.

The value of their rights will depend on the difference between the subscription price and the ruling market price. The larger this discount, the more shares will have to be issued to raise the required 3.95b – but only from its own shareholders. Hence there need be no dilution of shareholders. The market value of TFG must have increased by at least R3.95b for the shareholders to break even on their additional investment. They will be hoping for more upside over time. And some of the upside may even have been registered already in anticipation of the rights issue going through, even before the announcement of the rights issue itself, because of the better times it portends for the company.

The larger the difference between the ruling market price and the price at which the additional shares will be offered (the larger the discount) the more likely the rights will have value and be taken up. This outcome is only of importance to the underwriters. The more enthusiastic the response, the fewer shares the banks will have to take up. Presumably in this case the intention of the underwriters is not to hold shares in TFG.

A rights issue is equivalent to an additional investment by a sole shareholder in a company. The nominal value attached to the additional shares will be of no consequence other than to determine the number of extra shares issued, as identified in the books- all with the same owner. In practice the additional capital invested in a non-listed business is very likely to be identified as loan rather than share capital, to enable the owner to rank equally with other creditors in the event of a business failure

The issue of relevance to shareholders is will the extra R3.95b. of capital raised will pay for itself over time. That is earn a return over time on the R3.95b of additional capital that more than covers the cost of the capital raised. To add value for shareholders such future returns would need to average around 12-13 per cent per annum. That is to presume that the required returns from a retailer in SA would have to be at least equal to the returns certainly offered by a long dated government bond (currently about 9% p.a) plus a risk premium of 4% premium. They could hope to realise similar returns from any other JSE company taking similar risks with their capital. If the answer is a positive one, that is to say expected returns promise economic profits or economic value added (EVA) the rights issue or indeed any secondary issue (regardless of any dilution that might take place) should be approved.

There is a further consideration that established shareholders will bear in mind when approached for additional capital. The value of their shares will have declined in response to the damage caused to earnings and cash flow by the disruption of their ordinary activities caused by the lock down. Hence the need for additional capital. Companies that entered the lock down with relatively debt laden balance sheets will be recognised as more vulnerable to financial stress. However the prospect of a rights issue that would mitigate this danger would always be reflected, favourably, in the current value of the shares.

Any unexpected failure of shareholders to approve a share issue of this kind would surely raise the likelihood of default and immediately reduce the value of a shareholding. Not throwing good money after bad may be the right decision. But if it comes as a surprise to the market place such a refusal will provides a very negative signal. Vice versa if a surprising rights issue is successfully launched.

A successful secondary issue, underwritten by bankers, that does not demand participation by possibly jaundiced established shareholders, is perhaps an even stronger signal of favourable longer- term prospects for any company. The avoidance of dilution should not be a primary consideration in any capital raise. If the additional capital is expected to realise an economic profit, established shareholders will benefit in line with newly attracted shareholders. They can expect to have a smaller share of a larger cake and be better off for it.

The more obvious way to avoid dilution of established shareholders is to raise extra debt rather than equity capital. But the market for debt issues may not be as open as the equity market. As would appear to be the case in SA, but not in the USA. But more debt as we have seen makes any company r more risky. Andwhen business as usual is disrupted debt becomes particularly burdensome. Debt is not always cheaper than equity. It may appear so in the good times that may not last.

The same positive answer is required of any business large or small post Covid that needs to raise debt or equity capital to resume business post Covid. That is will it earn economic profits in the true opportunity cost sense? Will the investment beat its cost of capital, that is return more than is required to justify the investment? We must hope that the SA financial markets, including most importantly the banks, can meet these additional, fully justifiable calls for extra capital. The government with its central bank has the task of ensuring that the capital market is up to this vital task.