What is deemed to be right for the increasingly indebted developed world hoping to recover from the coronavirus – that is massive doses of extra government spending and money creation in support of government debt – is treated with suspicion when proposed or attempted by increasingly indebted emerging market economies, including SA.

We have argued that economies such as our own, which have suffered even more damage from the lockdowns, thanks to more widespread poverty and in the absence of capital reserves accumulated by households and businesses, need all the unconventional help they can get.

Not all emerging market central banks have taken the chastity vow. In Indonesia, as the Financial Times (FT) reported on 15 June: “Finance Minister, Sri Mulyani Indrawati, says quantitative easing and other policies are restoring confidence. Indonesia is at the forefront of emerging markets in implementing monetary policy that was once seen as the preserve of developed economies.”

The minister said that “Indonesia will use unprecedented quantitative easing and other emergency monetary and fiscal policies for as long as it takes to recover from the coronavirus pandemic, according to the country’s finance minister. With the private sector in retreat after weeks of lockdown, massive state spending was needed to shore up the economy”, adding that Indonesia would not rely on central bank financing in the long run: “That is not good policy practice.”

Brazil, according to the FT in another report (8 June) has granted its central bank extraordinary powers for the next 12 months, even though the Bank seems somewhat reluctant to employ them. Central bank President Roberto Campos Neto said he would not employ such measures until traditional tools had been exhausted:

The case for extraordinary policies is clear enough. When economies are allowed to normalise, hopefully extra demand will match extra potential supplies that then become available. Extra spending to accompany extra output can be assisted by extra government spending – on income relief and relief for lenders and borrowers. Money creation by central banks can make it cheaper to issue more government debt and to encourage banks to lend more freely. In the absence of stimulus, the willingness of firms to increase output and to offer employment on normal terms would be more compromised. They are unlikely to hold optimistic forecasts of revenues and profits upon which to budget. The case for stimulus is thus every bit as strong in the less developed world, including SA.

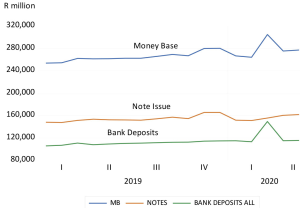

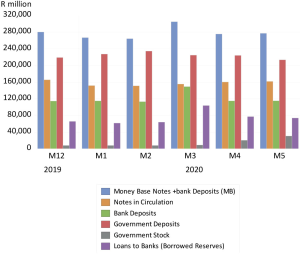

There is as yet no indication that the SA Reserve Bank sees the crisis as calling for anything like such a vigorous a response. It remains largely in conventional inflation-targeting mode. The supply of central bank money, notes in circulation together with the cash deposits of the banks with the Reserve Bank, defined as the money base or M0, sometimes more evocatively described as high powered money, did not increase at all since the end of last year to May 2020.

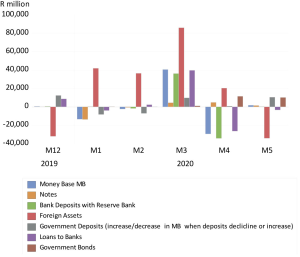

Government deposits are not part of the money base held by the public and the banks. An increase in government deposits reduces the money base and a decline will do the opposite, provided the drawdown is used to fund spending or debt repayments in SA. If, as appears to have been the case in May 2020, the payments by the government (drawing down its deposits) went to foreign creditors and so foreign banks, the SA banks will thus not have seen an increase in their cash reserves and deposits with the Reserve Bank. In May, the loans to private banks declined sharply – also reducing the money base. Thus, despite the purchase of an additional R10bn of government stock by the Reserve Bank, the money base in May was practically unchanged and no larger than it was in December.

In the charts below, we show the Reserve Bank balance sheet over the period since December and the monthly changes in some of the key items that move the money base – the notes in circulation plus the deposits of the banks with the Reserve Bank.

The money base in SA and its sources (December 2019 to May 2020)

Source: SA Reserve Bank Balance Sheets and Data Bank, and Investec Wealth & Investment

Reserve Bank balance sheet – monthly movements affecting the money base (December 2019 to May 2020)

What is called for is firstly a properly vigorous response to the crisis. It also calls for a credible commitment to a return to fiscal and monetary normality when the crisis is over, and when the economy is operating at something like its potential. That long-term growth potential surely has to be above 2% annual growth. To realise permanently faster growth, needs more than effective crisis management. It calls for reforms of the economy.