January 9th 2019

If you could borrow as much as might wish at close to zero rates of interest for ten or more years you would surely do so. There would be no lack of projects that promised wealth generating returns of at least one per cent p.a. Of course such funding opportunities are not readily available to any ordinary business or household. Lenders would demand a premium to cover risks of default and would raise the prospective returns potential investors would have to achieve.

But such considerations do not apply to the German, Japanese, Netherlands or even the Brexit stressed UK government or the Swiss that can borrow at negative rates of interest. Lenders pay for the privilege of funding the Swiss government – for ten years and more. These governments can borrow as much as they might wish at very low rates.

Surely an extra bridge or highway, port or pipeline or even a dyke helping to create a productive polder can promise a one per cent per annum return? Governments with such favourable credit ratings neither have to undertake the construction nor the management of such low return projects that can be leased to private operators- who win competitive tenders to do so. And if governments would exercise such opportunities to borrow more at invitingly low rates – also, heaven forbid, to cut income and expenditure tax rates – aggregate demand for goods and services would be stimulated. And businesses would add to their productive capacities, including their work forces. And depressed rates of growth of GDP and accompanying incomes would accelerate.

Demands for credit especially bank credit would be encouraged, bank balance sheets would strengthen, while the national savings rates declined and interest rates could rise for very good reasons. Because demands for capital to invest would be rising rise faster than supplies of savings.

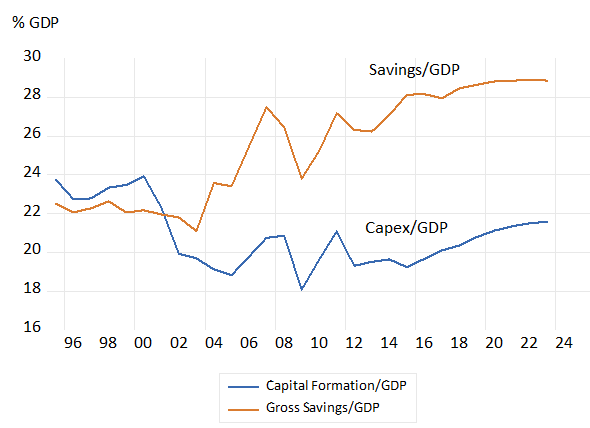

The failure to respond to respond sensibly to an extraordinary level of savings and the accompanying low interest rates is the essential European economic problem. The rate at which the Germans have saved has increased dramatically since 2000, while the rate at which they have added to their stock of capital fell away.

Germans in 1995 saved about 22% of their incomes- a very high rate for a developed economy. They are now saving 28% of their very large GDP that is forecast to rise further.They add to their capital stock at a 20 per cent of GDP rate. This has meant dramatically larger flows of capital out of Germany into global capital markets. In 2018 outflows of about 400 billion dollars were estimated.

Savings and Capital Formation ratios to GDP in Germany. Annual data

Source; IMF World Economic Outlook 2018 and Investec Wealth and Investment

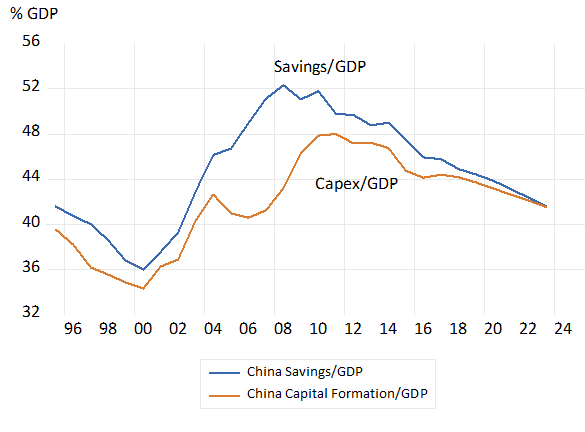

The Dutch are now saving a similarly high proportion of their incomes and the Japanese are a further major source of global savings. The Chinese save at an even higher rate, over 40% of GDP, though the rate at which savings are made and capital formed has been falling. China is no longer a significant contributor to the global savings pool. A fact that may well inhibit its ability to stimulate its economy.

China – saving and capital formation to GDP ratios. Annual data

Source; IMF World Economic Outlook 2018 and Investec Wealth and Investment

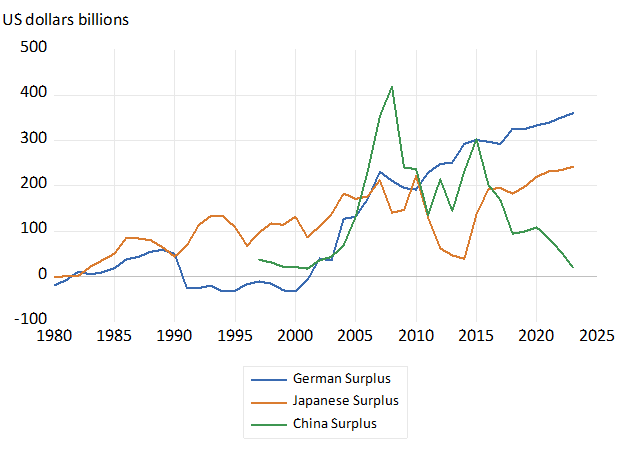

Contribution to global capital markets. The combined surpluses of Germany, Japan and China (US dollar billions)

Source; IMF World Economic Outlook 2018 and Investec Wealth and Investment

The contribution in 2007 to the global savings pool from China, Germany and Japan amounted to nearly a trillion US dollars – compared to about a mere $100b seven years before. It is now about $600b.

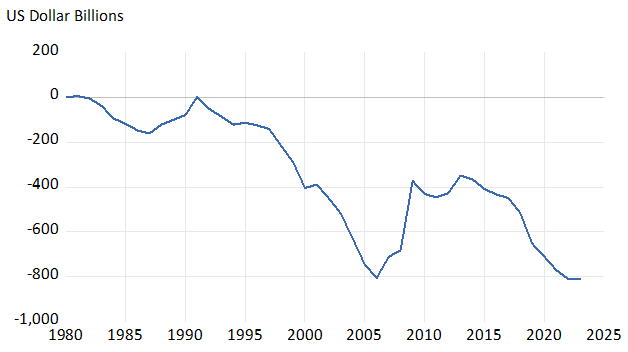

The borrowers to absorb these surpluses at low interest rates were naturally found in the credit hungry US. Inflows of capital to the US expanded dramatically after 1995 – much of it funding houses that had to be abandoned by their owners after 2008. The average US home lost 30% of its pre-global financial crisis value. No mortgage based financial system could hope to survive a collapse in asset values of this magnitude- without a bail out.

US capital inflows 1980- 2023 – A tale of growing dependence.

Source; IMF World Economic Outlook 2018 and Investec Wealth and Investment

Less not more austerity is urgently called for in northern Europe- to help save the euro and the European project. The Italian and other populists are on the right track while the German fiscal conservatives perversely continue down a dead end.